Welcome to the Research Open House 2021!

We’re happy to announce this year’s Research Open House winners in the categories of Sustainability, Innovation, Impact, Start-Up Power, and the People’s Choice Award. Congratulations!

Thank you to everyone who has supported research at Pratt Institute and your enthusiasm for this year’s Research Open House. We’re so grateful for our community and we hope that you continue to enjoy the site.

Please be in touch with the Office of Research & Strategic Partnerships with any questions or to discuss a potential project or collaboration by emailing research-partnership@pratt.edu.

Welcome Letter

We could not have imagined that last year, when we decided to move online the annual Pratt Research Open House, we would still be working remotely a year later. This time has been challenging for all of us, which is why we are so impressed and humbled by the work of the Pratt research community as they have pushed through this unprecedented time with grace, humor, and tenacity. We are very proud of the deeply thoughtful, impactful, and truly unique research that they continue to pursue, and share their progress here.

Since establishing the Office of Research & Strategic Partnerships in the Office of the Provost, our mission has been to support and cultivate research at Pratt in all its various forms. A few of these forms have been the Research Seed Grant program, of which you’ll find some updates from projects from the 2019–2020 year on this year’s site; our Provost Centers’ diverse research that focus on robotics, sustainability, community development, and spatial analysis; and our day-to-day efforts in mentoring and championing our research-active faculty, staff, and students.

When we meet with people both within and outside of the Institute, we’re often asked what exactly we mean by “research” at Pratt Institute.

When we say research, we mean involving the communities we design, work, and teach with to inform and expand what is possible. If you ask yourself how your work can solve problems, impact an audience, and then how impact will be measured…we think that can add up to important research.

When we say research, we mean becoming mindful of the personal artistic practice and design process to consider how that process affects outcomes. If you ask yourself what happens if the medium, materials, audience, or approach are changed…that too is research people need to learn from.

When we say research, we also mean adapting the ways and processes of making and designing in a world that is reckoning with broken systems and the need for change. If you ask how to ethically approach a design problem, and how to accomplish something in a more sustainable, equitable, or innovative way…that too is research.

With all that is research, we are thankful that so many people at Pratt lead the way.

We hope that you will enjoy this glimpse of the ongoing research at Pratt and be in touch with us about the incredible work that has been done and the inspiring work that is on the horizon.

Our research best,

Allison Druin, Ph.D.

Associate Provost of Research and Strategic Partnerships

Kathryn Kelly

Manager, Office of Research and Strategic Partnerships

Congratulations to all of our award winners! We celebrate your commitment to your research, particularly in this challenging time, and your noteworthy contributions and achievements. We can’t wait to see where your research goes from here!

Sustainability Award

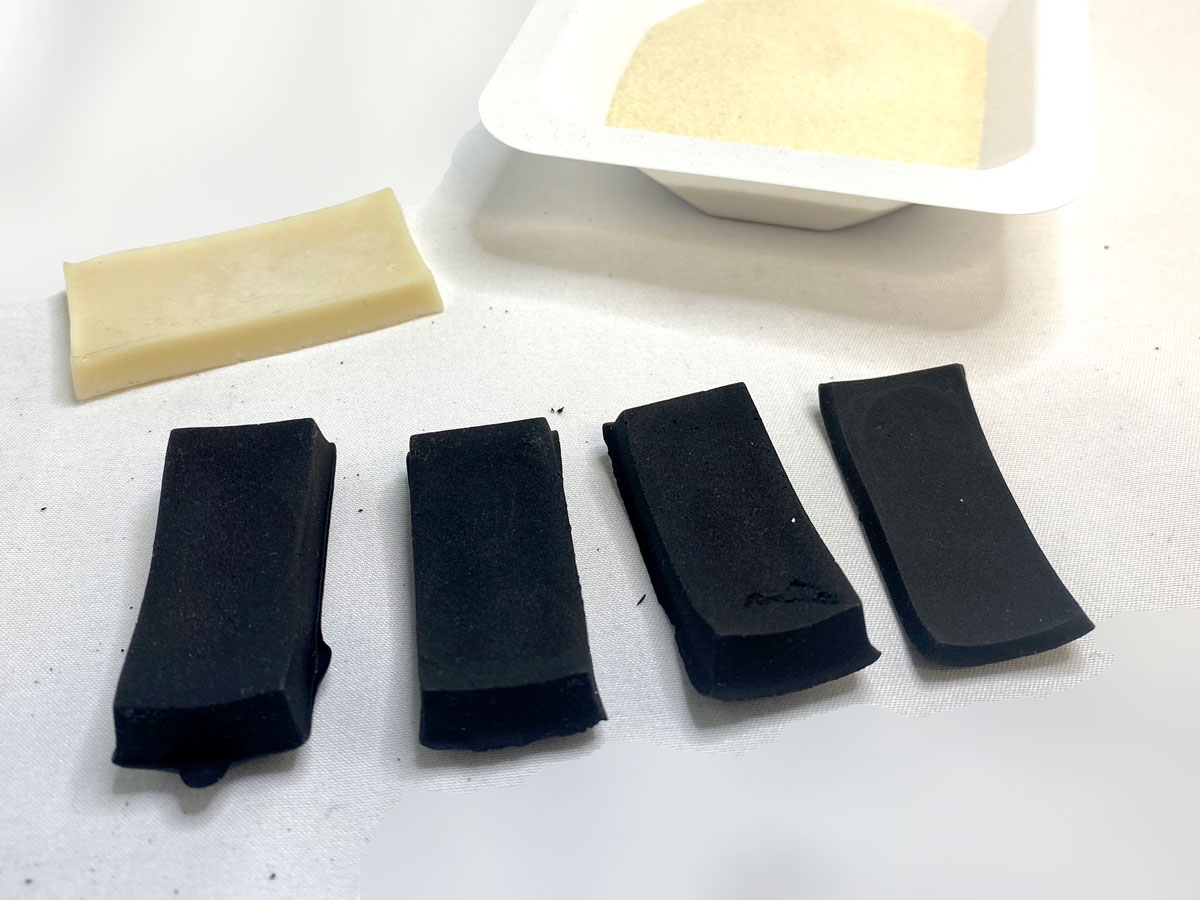

Bioplastics are the counterpart to the petroleum-based plastics made of biopolymers. They are biodegradable, made from renewable raw materials such as gelatin, starch, and other biopolymers. Although the materials are not new, we now have technologies and methodologies that can help us create everyday products out of bioplastics to replace traditional plastics.

Innovation Award

Sonic Bloom is a soundscape that helps plant owners understand the status of a plant’s health by creating an efficient monitoring system. Using the internet of things, the soundscape behaves as an interface stimulating a deep connection between the plants and their owners.

Impact Award

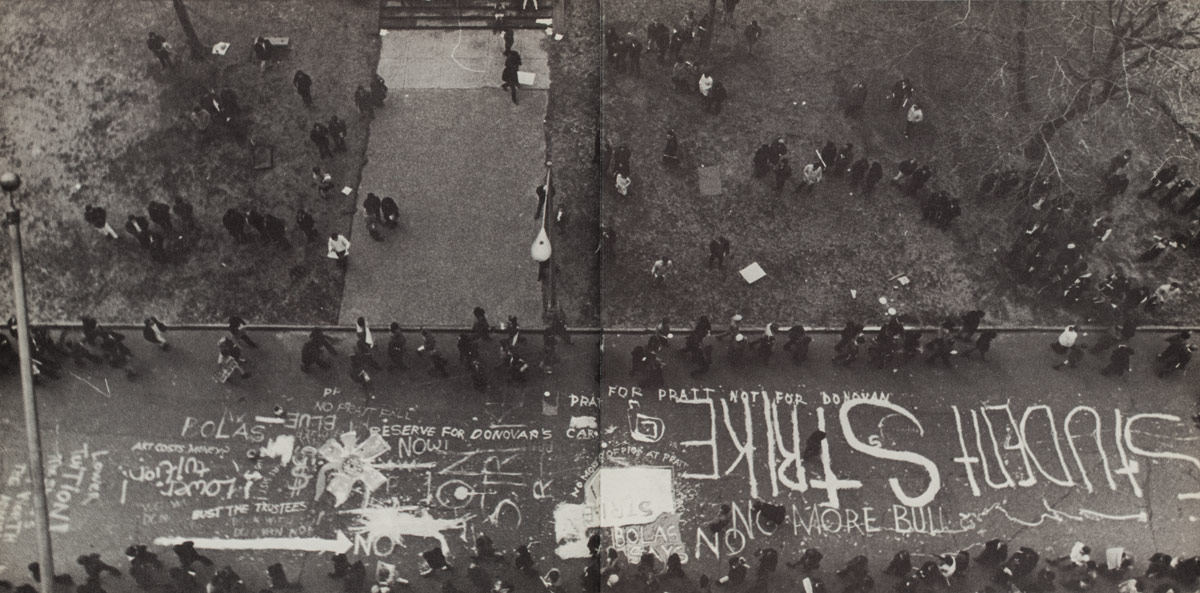

The interdisciplinary Preserving Activism project team conducts historical research that seeks to foster public dialogue about social justice activism between and beyond Pratt’s gates. This past year faculty and students worked with the Institute Archivist to examine 20th century activism at Pratt through coursework and the collection of oral histories, texts, and ephemera that will become part of the Archives.

Impact Award

A Civic Shift is a series of performative digital events bringing contemporary artists, grassroots organizers, and NYC City Council candidates into dialogue around pressing sociocultural issues to investigate how our collective imagination can foster progressive change in the time of COVID-19.

Start-Up Power Award

The Wing Guard is a biomimicry insect repelling device that mimics the visuals, sounds, and motions of the dragonfly to stop flies from landing on food items. It aims to combat the hygiene problem of places that rely on temporary food service establishments, such as wet markets and open-air farmer’s stalls.

People’s Choice Award

Fashion, Identity and the Muslim-American Narrative is a design workshop series developed for and with Muslim-American female adolescents. The goal was to highlight the direct correlation between awareness, agency, and perception of dress and self-esteem established with ownership of one’s authentic narrative.

I am pleased to announce this year’s Research Recognition Award, the recipient of which is selected by committee through Pratt’s Academic Senate. The award is one of the highest honors of achievement at Pratt Institute. This annual award is given to a person who has made significant impact on academic research, has achieved impressive critical review and reception, and—not least—has cultivated strong ties to the Pratt Institute community.

This year’s recipient of the Research Recognition Award for 2020-2021 is Dr. Macarena Gómez-Barris, Chair of the Department of Social Science and Cultural Studies in the School of Liberal Arts and Science, and founding director of the Global South Center.

In her five years at Pratt, the contributions of Dr. Gómez-Barris have been far-reaching and impactful, from supporting colleagues in the development of their research within her department, to founding the Global South Center, which has hosted more than one hundred visiting scholars.

We are grateful for her contributions to Pratt Institute, her commitment to knowledge creation and sharing, and her determination to traverse the perceived boundaries of disciplines and geography.

Sincerely,

Kirk E. Pillow

Provost

DR. MACARENA GÓMEZ-BARRIS

Dr. Macarena Gómez-Barris is a scholar and writer who works at the intersections of the environment, decolonization, visual arts, memory, and land and sea restitution. She is the author of four books, Where Memory Dwells: Culture and State Violence in Chile (2009), The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (2017), Beyond the Pink Tide: Art and Political Undercurrents in the Américas (2018), and Towards a Sociology of a Trace (2010, with Herman Gray). She is completing a new book on what she terms the colonial Anthropocene, At the Sea’s Edge: Liquid Ontologies Beyond Colonial Extinction (Forthcoming Duke University Press 2022). She is series editor with Diana Taylor of Dissident Act, Duke University Press. She is Founding Director of the Global South Center (globalsouthcenter.org) and Chairperson of the Department of Social Science and Cultural Studies at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn. She is the recipient of a Fulbright Award, the 2020-2021 Pratt Research Recognition Award and the 2020-2021 Distinguished Alumni Award from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Q+A WITH DR. GÓMEZ-BARRIS

How would you describe your research and its practice?

My research is rooted in my ethical, social, and political commitments. As an immigrant and exile from Latin America, I learned the importance of engaged research and practice from an early age. Studying Sociology and the devastation of neoliberalism and authoritarianism led me to publish my first book Where Memory Dwells: Culture and State Violence in Chile. I ended that book by describing how the submerged memory of the Rio Mapocho, a river in Santiago that had been used to dispose of those disappeared and killed by the Pinochet regime, overflowed one fateful stormy day. The metonym of the river’s repressed return was a way for me to express the legacies of state and US imperial violence as well as resistance to it.

Focusing on repressed memory led to my work on extractivism and the documentation of Indigenous communities. Through visual arts, building relationships, and engaging with decolonial theory and praxis I showed how territory, and land and water “resources” are the wreckage spaces of colonial violence. Theorizing memory, power, and extractive zones within geographies of Indigenous land and water protection led me to see and perceive the importance of what I call submerged perspectives.

As a researcher traversing numerous subjects simultaneously, how do you balance the varied ontologies of your research while still deeply engaging with the material?

It has taken me many years to develop methodologies that are accountable to those I research and whose lives are impacted by state and colonial violence. Mere historical description does not get at the layers of historical terror committed against Black, Indigenous, subaltern peoples and racialized geographies in the Global North and the Global South. Focusing on visual arts, documentary films, memorials, social movements, and learning from Black and Indigenous scholars, queer of color critique, critical ethnic studies, Native, Black, and transnational feminisms has allowed me to develop a decolonial queer approach to my work that foregrounds others’ voices as well as situates myself in my research.

For those researchers that don’t want to be restricted by disciplines and push against traditional research frameworks, what advice would you give?

My advice is stay with your practice. Disciplines within the humanities and social sciences are essential in that they teach specific ways to engage the texture of social life, theories of power, and the history of ideas. We cannot innovate if we do not understand how we got here. For me, mapping decolonial thought as well as learning from the the practices of the mothers of the disappeared, working with women former combatants in repatriated communities in El Salvador, working in solidarity with the Mapuche people, being a part of arts and intellectual communities in Ecuador, Chile, Beirut, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and now in Brooklyn and New York, all of that has been key to my practice.

But in the end, I have given myself permission to not stay within the specifications of a single discipline, and I have prioritized my writing and speaking as a practice. I am not afraid to make my political and ethical commitments known. And, I continue to evolve this work on a daily basis, yet I often hit roadblocks and frustrations. At this point, I’ve learned that creating good work means that there will be more obstacles than not. And, the final work will be better precisely because of these challenges.

What is the biggest challenge you’re currently facing as a researcher?

The pandemic has exposed white supremacy again, and the massively differential impact that immiserate, dispossess, and deplete communities of color exponentially. I am currently researching Black and Indigenous ontologies in the Américas. I had planned to go to the Panama Canal in July of last year in order to research a key chapter of this current book project, a research stay that obviously did not happen!

Given that I rely on experiential knowledge, interviews, engaging community knowledge, listening, and walking in the places I write about, this felt like a set back. Yet, I realize that I cannot rush my academic and creative work, especially during this particular time of urgency and ongoing emergency. So the challenge is balancing my own self expectations and timelines in the context of the current global health crisis.

What was the biggest challenge when you first started your research journey?

My biggest challenge was never having enough funding to do international research. As a graduate student conducting international field research I did it all on a credit card. It took me decades to pay off student debt. In my book Beyond the Pink Tide the first chapter addresses student debt, the massive constraints it puts on young people, and how student movements focused on debt and credit are so essential. My son, Renato, has consciously chosen to go to a public university this coming Fall. He chose low tuition and a “no debt” future precisely because this is such a big topic of conversation in our household. Student debt imprisons generations of young people; Education should be state subsidized, period.

What are you most proud of having accomplished as a researcher?

The more than 200 activists, scholars, and artists we have invited to speak, participate, and dialogue with us at the Global South Center has truly shaped my research. All of these participants work towards radical justice through their scholarly and artistic approaches, as well as providing unique visions of how to do this often. Working with my colleagues in the Global South Center has helped shape my research trajectory, and personally represents an important accomplishment. The Global South Center models a trans-disciplinary approach to research and action. I am grateful for this award for my research and the recognition by my peers at Pratt, such an enlivened arts and design context to work in. This award means that the critical labor we do in the humanities, the environmental humanities, social sciences, critical and visual studies is seen and supported, especially at a time when context-driven research is crucial.

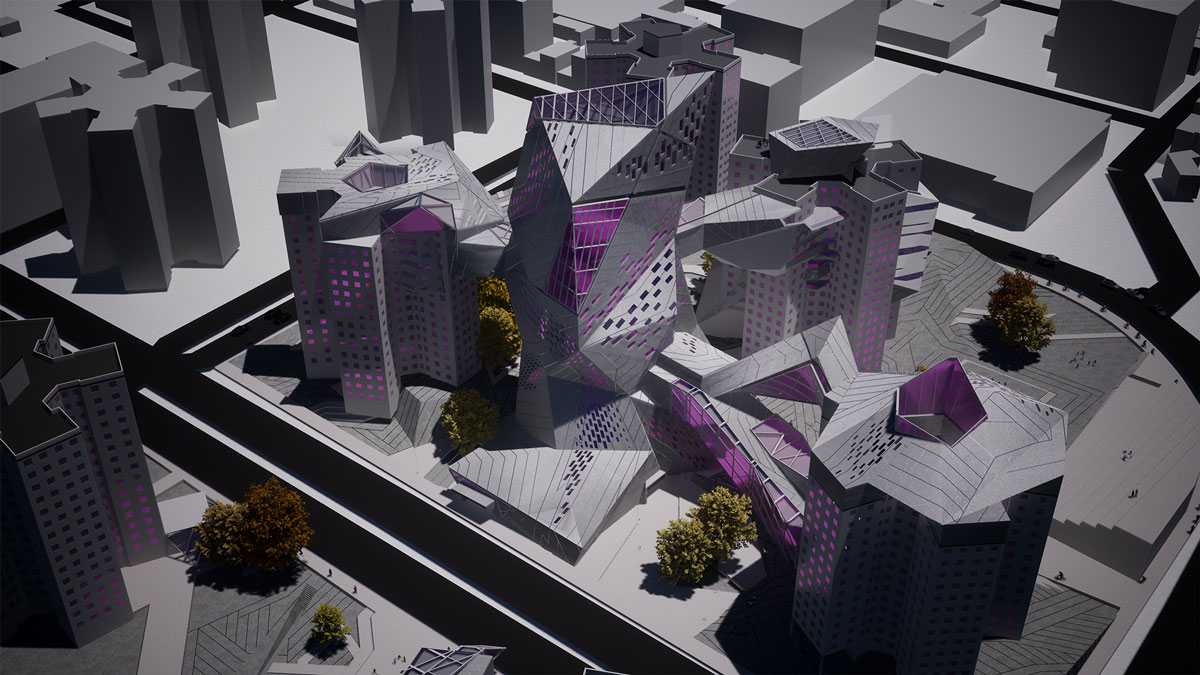

Submissions from the School of Architecture are deeply focused on positioning technologies and the built environment in conversation and harmony with the natural world and/or previously built environments. There’s also a particular focus on shifting architectural practice, making, and theory to reflect the evolving world, impacted by COVID-19 and climate change.

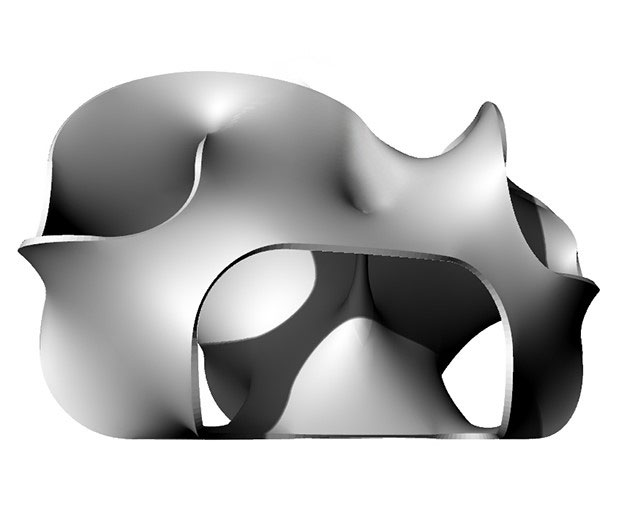

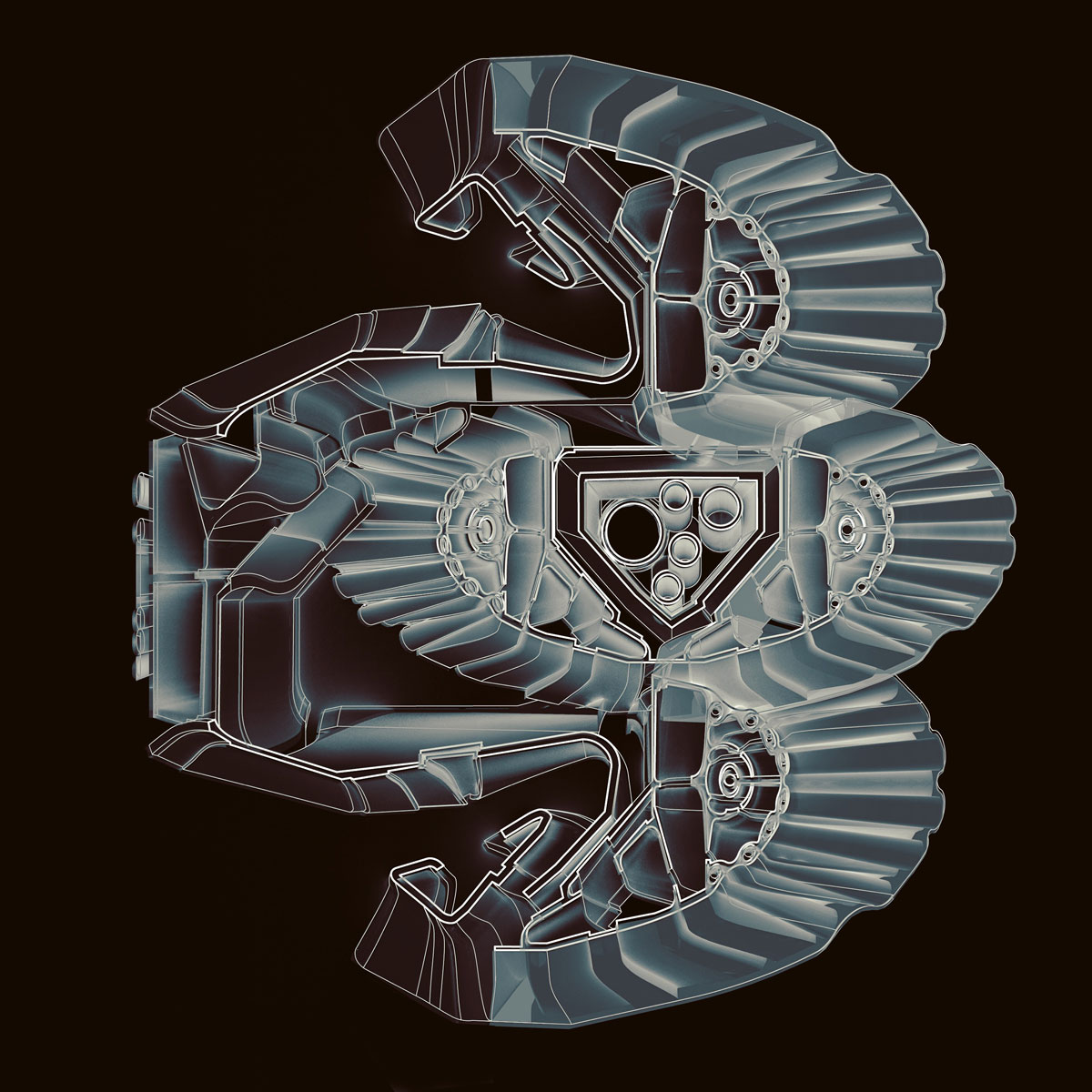

Haresh Lalvani

School of Architecture, Center for Experimental Structures

This multi-year project (interrupted by covid-19) is now in its last phase of fabrication, with the intention of an outdoor installation at Pratt Institute in the Fall of 2021.

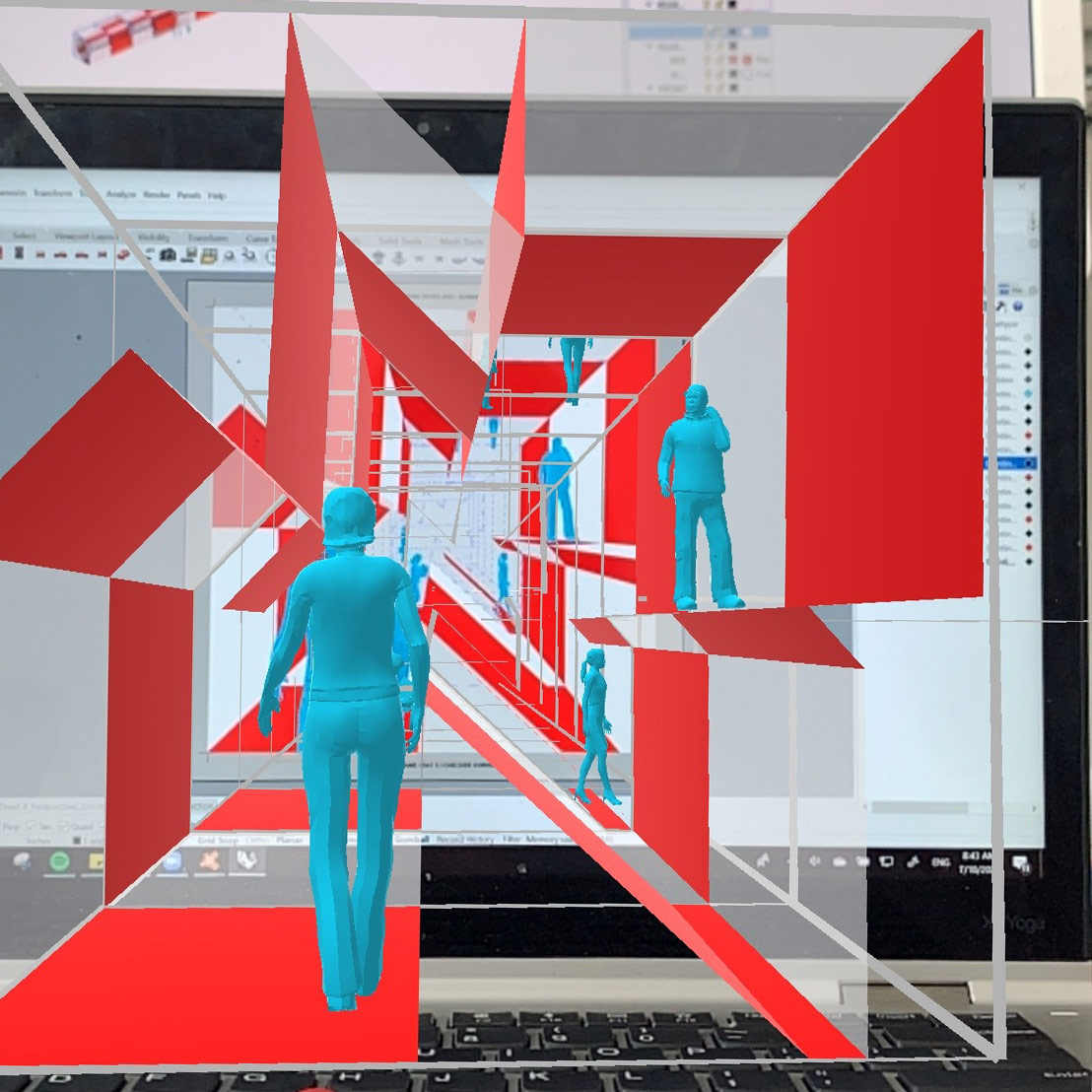

Jonathan A. Scelsa

School of Architecture, Undergraduate Architecture

K-12 Seed Grant 2019-2020

Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) Fellowship 2019-2020

Augmenting the Digital Review serves as an investigation into the use of augmented reality technology within early architectural education, as a means of introducing both historical and contemporary tools of abstract making and seeing.

Jerrod Delaine

School of Architecture, Construction /Facilities Management, Real Estate Practice

The Covid-19 outbreak in America in the spring of 2020 has disproportionately impacted the Black community in America, exposing long-standing vulnerabilities. This impact has shed a long-overdue light on the connection between wealth, health, housing, and race in America. This research explores what extent financial incentives encourage communities to improve diversity in homeownership. And, in turn, to what extent that will improve the community physically, socially and economically.

Ane Gonzalez Lara

School of Architecture, Undergraduate Architecture

Southern New Mexico is a land of harsh contrasts, sublime landscapes, and silenced stories. The region selected for this work, the Lower Rio Grande Valley, encompasses the counties of Socorro, Doña Ana, Sierra, Otero, and Luna.

Jeffrey Anderson and Ahmad Tabbakh

School of Architecture, Graduate Architecture and Urban Design

This project demonstrates the possibility of creating an accurately aligned physical-digital hybrid experience to augment a physical art installation. The exhibition design and fabrication was completed by Kyriaki Goti at Some People Studio and was built in Frederick, Maryland.

Niyousha Zaribaf, MArch ‘21

School of Architecture, Graduate Architecture and Urban Design

This 1:1 façade prototype explores the hybridization of two architectural and non-architectural systems within the context of the climate crisis. With the configuration of three different layers (1) hidden object, (2) interstitial space, and (3) outer shell, the natural ventilation system becomes an architectural system to be analyzed.

Ariane Harrison

School of Architecture, Graduate Architecture and Urban Design

The Pollinators Pavilion is an analogous habitat for native, cavity-dwelling bees. The structure both communicates data harvested from its monitoring system—addressing the gap in scientific knowledge on native bees—and introduces these overlooked yet critical pollinators to a broad public to promote biodiversity and ecosystem restoration.

Pankti Mehta, MS Sustainable Environmental Systems ‘20

School of Architecture, Graduate Center for Planning and Environment (GCPE) and Sustainable Environmental Systems (SES)

Green Infrastructure (GI) implementation is often prioritized based on a singular problem: stormwater runoff. GI, however, is argued to have multiple co-benefits, raising the question: why aren’t these co-benefits accounted for prior to implementation?

Niyousha Zaribaf, MArch ‘21; Runxue Guo, MArch ‘21; and Zhuojun Yun, MArch ‘21

School of Architecture, Graduate Architecture and Urban Design

Aggressive mining is happening today worldwide, resulting in a changed landscape. The quarry brings new texture to the earth, but the process pollutes the water.

The Pulsating Gardens use the Daoism philosophy of Chinese painting to hybridize mining space and the existing conditions of Shandong Mining Park in Zibo, China, in order to show a potential harmony between human activities and nature.

James Nanasca, MArch ‘22 and Rohan Saklecha, MArch ‘22

School of Architecture, Graduate Architecture and Urban Design

Inspired by Lebbeus Woods’ Sarajevo Reconstruction Project, this design re-imagines the idea of “Free Space,” as new and flexible public spaces for the residents of the Farragut Housing Community.

Maria Sieira

School of Architecture, Graduate Architecture and Urban Design

Richard Rothstein’s research has shown us that during World War II and immediately afterward, there were opportunities to build new integrated cities in the United States, as they doubled or even quadrupled in population when new, much-needed factory workers arrived. Instead, efforts by the Federal Housing Commission kept white families and African American families segregated. Specifically, the African American families were forced to remain in housing that was meant to be only temporary, while white families were given low-rate mortgages towards ownership in the suburbs.

Duks Koschitz and Che-Wei Wang

School of Architecture, Undergraduate Architecture

In terms of global carbon emissions, the built environment is a major culprit; and the d.r.a (Center for Design Research in Architecture) aspires to find novel solutions for lightweight structures, since they can have a much smaller footprint than conventional building methods.

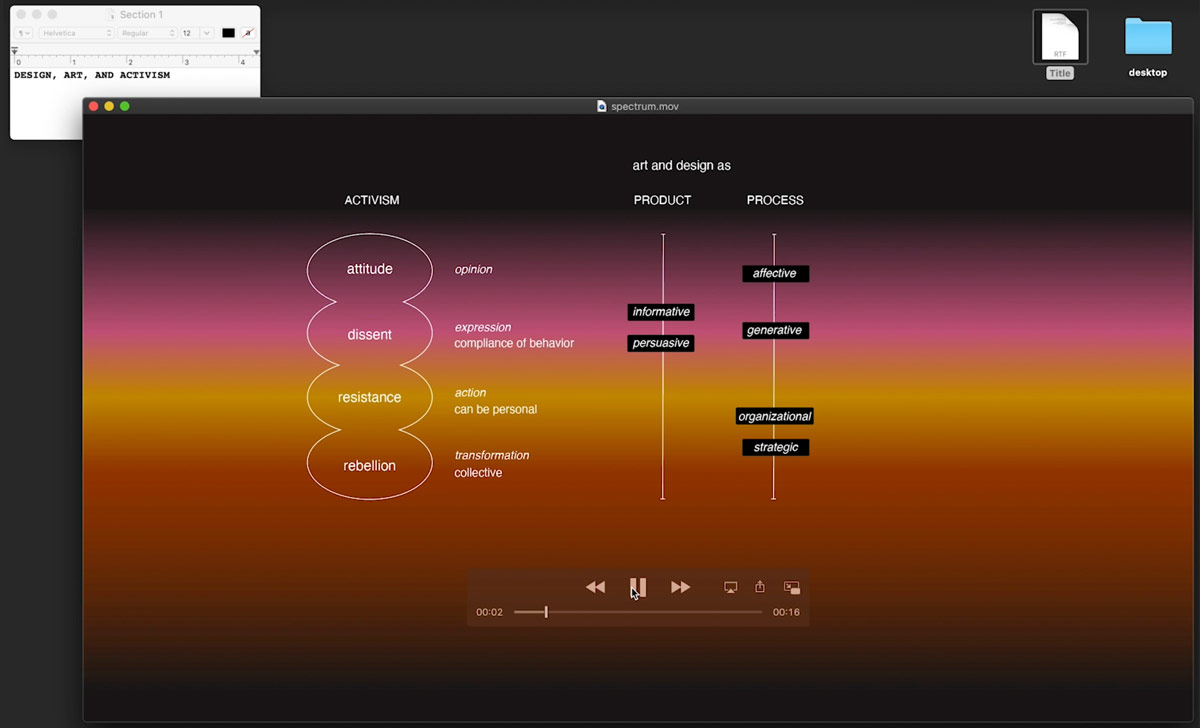

Amy Khoshbin and Dina Weiss

School of Art, Fine Arts

A Civic Shift is a series of performative digital events bringing contemporary artists, grassroots organizers, and NYC City Council candidates into dialogue around pressing sociocultural issues to investigate how our collective imagination can foster progressive change in the time of COVID-19.

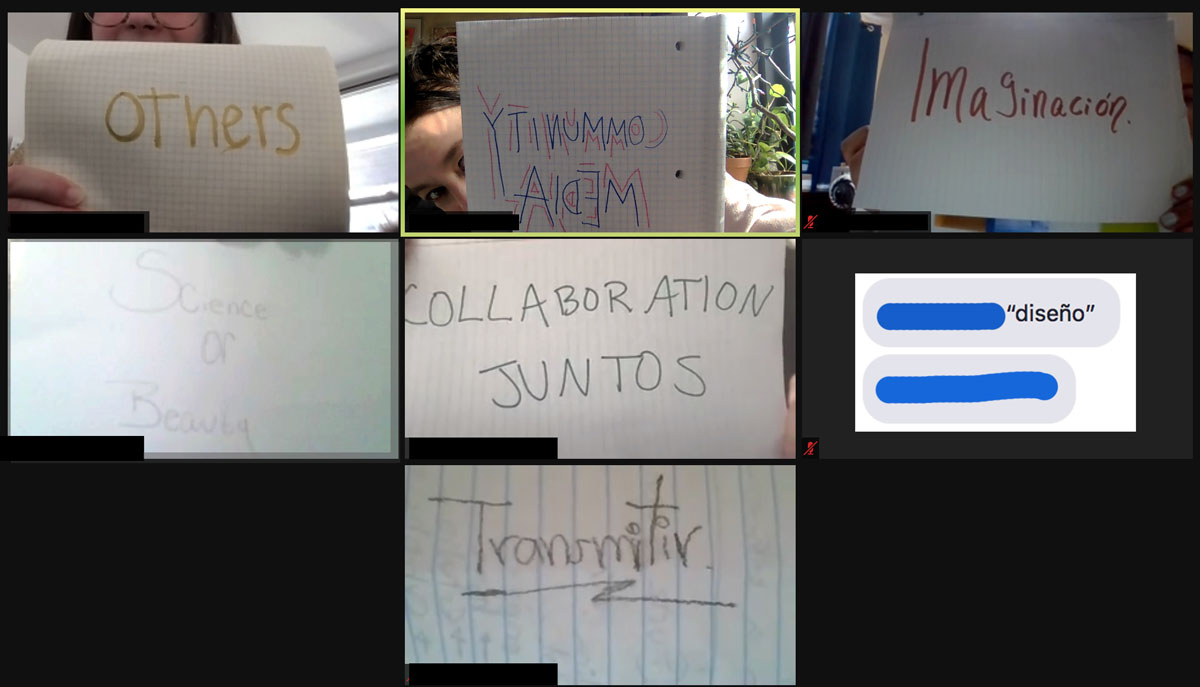

Dina Weiss and Langdon Graves Amy Khoshbin, Fine Arts Civic Engagement Fellow

School of Art, Fine Arts

After shifting to an online paradigm to deliver our fine arts curriculum last spring, we developed focused faculty forums to prepare for the new landscape of digital learning in the Fall 2020 semester.

Chloe Smolarski and Tasha Darbes, Pace University

School of Art, Digital Arts

In partnership with Gregorio Luperón High School, a bilingual STEM school in NYC, we are working with students to further understand the role creativity has in supporting immigrant youth in developing new forms of agency.

Jasmine Cho, MPS Art Therapy and Creativity Development ‘22

School of Art, Creative Arts Therapy

In 2019, I conducted an interdisciplinary research study that approached baking as a potential form of art therapy and measured its impacts on stress and anxiety in adults. Anxiety was measured via the State Trait Anxiety Inventory, and we measured stress by collecting saliva samples to analyze cortisol levels. The study showed that both self-reported anxiety and salivary cortisol levels significantly decreased after baking-as-art activities.

Robert Redding, MFA Painting and Drawing ‘22

School of Art, Fine Arts

As an independent artist, my social practice involves community engagement focusing on gathering feedback resulting from the partisan news treatment of out-group political participants. For independents, this means being able to participate in some states that allow them to identify as third party – Green, Libertarian and beyond.

Katarina Bennicoff Yundt, MS Dance/Movement Therapy ‘21 and Kelsie White, MS Dance/Movement Therapy ‘21

School of Art, Creative Arts Therapy

Reckoning with Whiteness is an arts and action based research study that seeks to further understand the role of white racial identity development as it pertains to the training of anti-oppressive dance/movement therapy students.

David Gothard, Fine Arts and Rachel Levitsky, Writing

School of Art

School of Liberal Arts and Sciences

The Third Mind project is a joint effort between students in the departments of Fine Arts and Writing. Students in Professor David Gothard’s course “Illustration and Symbolic Imagery” and Professor Rachel Levitsky’s course “Community as Classroom” engaged in a collaborative interdisciplinary project involving both illustrative, sculptural, installation, and written works.

Rhonda Schaller and Esmilda Hornbostel-Abreu

School of Continuing Education and Professional Studies

The Mindfulness Collaboratory will look at contemplative practices, including mindfulness and meditation, sitting and walking practices, and formal and informal expressions of self-awareness in order to aid artists and arts leaders in reimagining self and practice, business, and audience during COVID and within post-COVID contexts.

Anthony Pellino

School of Continuing Education and Professional Studies

Programming in Three Realms is a research project intended to draw upon knowledge obtained through presenting content (information, technical knowledge, narrative, et al.) to a public audience.

Yang Pei, MFA Interior Design ‘21 and Yawen Zhang, MFA Interior Design ‘21

School of Design, Interior Design

With the globalization of the pandemic, social distancing has become a notable part of our lives. By designing this installation, we hope to maintain social distance during the pandemic, while also bringing back a sense of intimacy now and in a post-pandemic world.

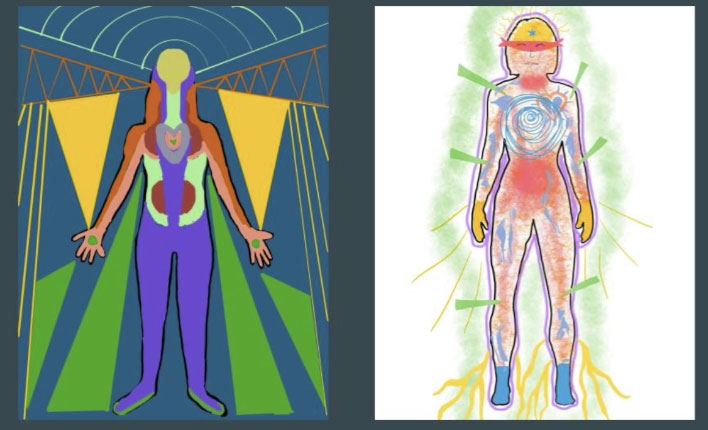

Sibylle Hornung, MFA Communications Design ‘21

School of Design, Communications Design

The term “human” refers to humans—the species homo sapiens—but also what was formed in societies as an European ideal and social studies about Humanism.

Shireen Soliman

School of Design, Fashion Design

Seed Grant 2019-2020

Fashion, Identity and the Muslim-American Narrative is a design workshop series developed for and with Muslim-American female adolescents. The goal was to highlight the direct correlation between awareness, agency, and perception of dress and self-esteem established with ownership of one’s authentic narrative.

Chia-Yuan Ko, MID ‘21

School of Design, Industrial Design

“AMPB” is the abbreviation for Amphibians.

Karen Kubey

School of Design, Interior Design

Seed Grant 2019-2020

Good Neighbors II is a comprehensive guide to affordable housing design in the U.S. and update to the seminal 1997 volume of the same title. The book and accompanying online resource will showcase exemplary affordable housing case studies from across the country and will revisit selected projects from the original publication. Good Neighbors II will address architects, developers, students, and communities considering affordable housing developments in their neighborhoods, and will examine the role of below-market housing in promoting health equity and economic, racial, and environmental justice.

Arianna Fouse, BFA Fine Arts ‘21

School of Design, Graduate Communications Design

Seed Grant 2019-2020

Our olfactory sense triggers memories—and by association, one might say that smell is linked to time in human perception. This experimental research is a sensory teaching tool to talk about the delicate complexity of our forests in a warming climate.

Nida Abdullah, Xinyi Li, and Chris Lee

School of Design, Undergraduate Communications Design

Post-Radical Pedagogy was convened as a space to explore, antagonize, challenge, and interrogate institutional values and legacies.

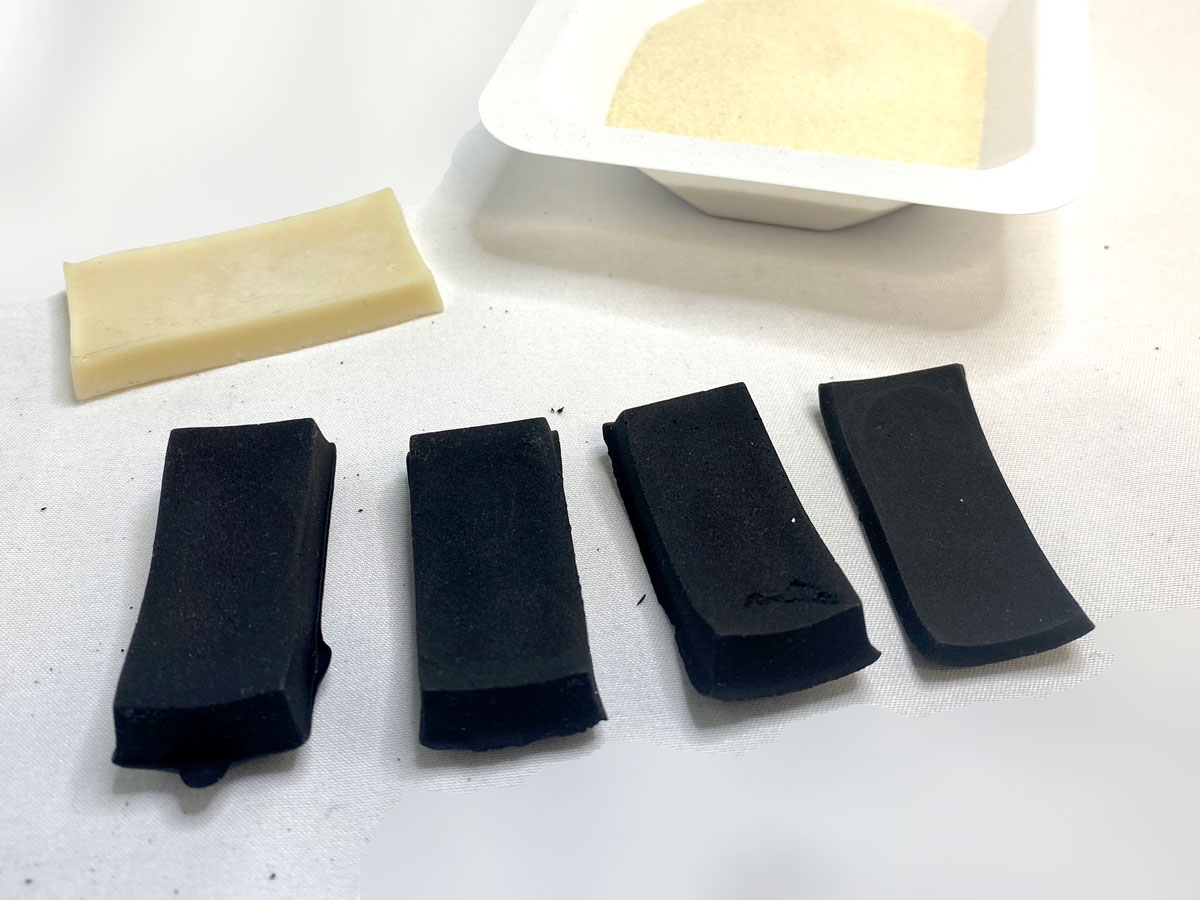

Kai Wen Chuang, BID ‘20

School of Design, Industrial Design

Seed Grant 2019-2020

The Social Practice Kitchen was built during the Fall semester of 2020, after the campus re-opened for hybrid learning. Since its completion, it has been utilized by different studio courses, events, and research projects. These include: biomaterial experimentation, 3D printed pasta explorations, candy casting workshops, and BYOM(ug) events where the Kitchen welcomed all in-person School of Design community members on a number of mornings with baked goods and a selection of tea. In mid-April 2021, Social Practice Kitchen will be a part of the Foundations Expanded project, activating public sites on Myrtle Avenue.

Anushritha Yernool Sunil, MID ‘22 and Archana Ravi, MS Information Experience Design ‘21

School of Design, Industrial Design

Sonic Bloom is a soundscape that helps plant owners understand the status of a plant’s health by creating an efficient monitoring system. Using the internet of things, the soundscape behaves as an interface stimulating a deep connection between the plants and their owners.

Jon Otis

School of Design, Interior Design

This research explores an innovative approach to investigate the relationship between space and sound. By observing site conditions, the environment, and culture, researchers will endeavor to investigate new spatial forms of expression and experience.

Xinyi Li

School of Design, Undergraduate Communications Design

This project uses cases from the early days of the pandemic to frame the concept of everyday digital resistance, unpacking the factors that contributed to the domination of this type of resistance.

Ellen Zhengyi Ren, BID ‘21

School of Design, Industrial Design

The Wing Guard is a biomimicry insect repelling device that mimics the visuals, sounds, and motions of the dragonfly to stop flies from landing on food items. It aims to combat the hygiene problem of places that rely on temporary food service establishments, such as wet markets and open-air farmer’s stalls.

Craig MacDonald and Elena Villaespesa

School of Information

The Center for Digital Experiences (DX Center) is a faculty-led, student-driven User Experience (UX) consultancy and academic research lab within the School of Information (SI).

Cristina Pattuelli and Matthew Miller

School of Information, The Semantic Lab

The Semantic Lab at Pratt’s E.A.T. project uses primary sources from the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Archive and linked data to create a repository of information related to Experiments in Art and Technology, a collaboration between artists and engineers in the 1960’s.

Sofia Martynovich, MS Information Experience Design ‘22

School of Information

Project Contrast seeks to explore and create a service for mindful donations embedded in urban context and powered by emotional design and data.

Cindie Kehlet and Helio Takai

School Of Liberal Arts And Sciences, Mathematics And Science

Bioplastics are the counterpart to the petroleum-based plastics made of biopolymers. They are biodegradable, made from renewable raw materials such as gelatin, starch, and other biopolymers. Although the materials are not new, we now have technologies and methodologies that can help us create everyday products out of bioplastics to replace traditional plastics.

Cindie Kehlet, Enrique Lanz Oca, Mary Lempres, Helio Takai

School Of Liberal Arts And Sciences, Mathematics And Science

The Center for Material Science is a new interdisciplinary initiative at Pratt. It focuses on research and applications of new materials aligning with an economic model that preserves the environment and respects social justice.

Macarena Gómez-Barris

School Of Liberal Arts And Sciences, Social Science and Cultural Studies

Macarena Gómez-Barris is the Founding Director of the Global South Center. In this brief presentation, she conceptualizes the war against the Earth, naming the differential impact of climate crisis as the colonial anthropocene.

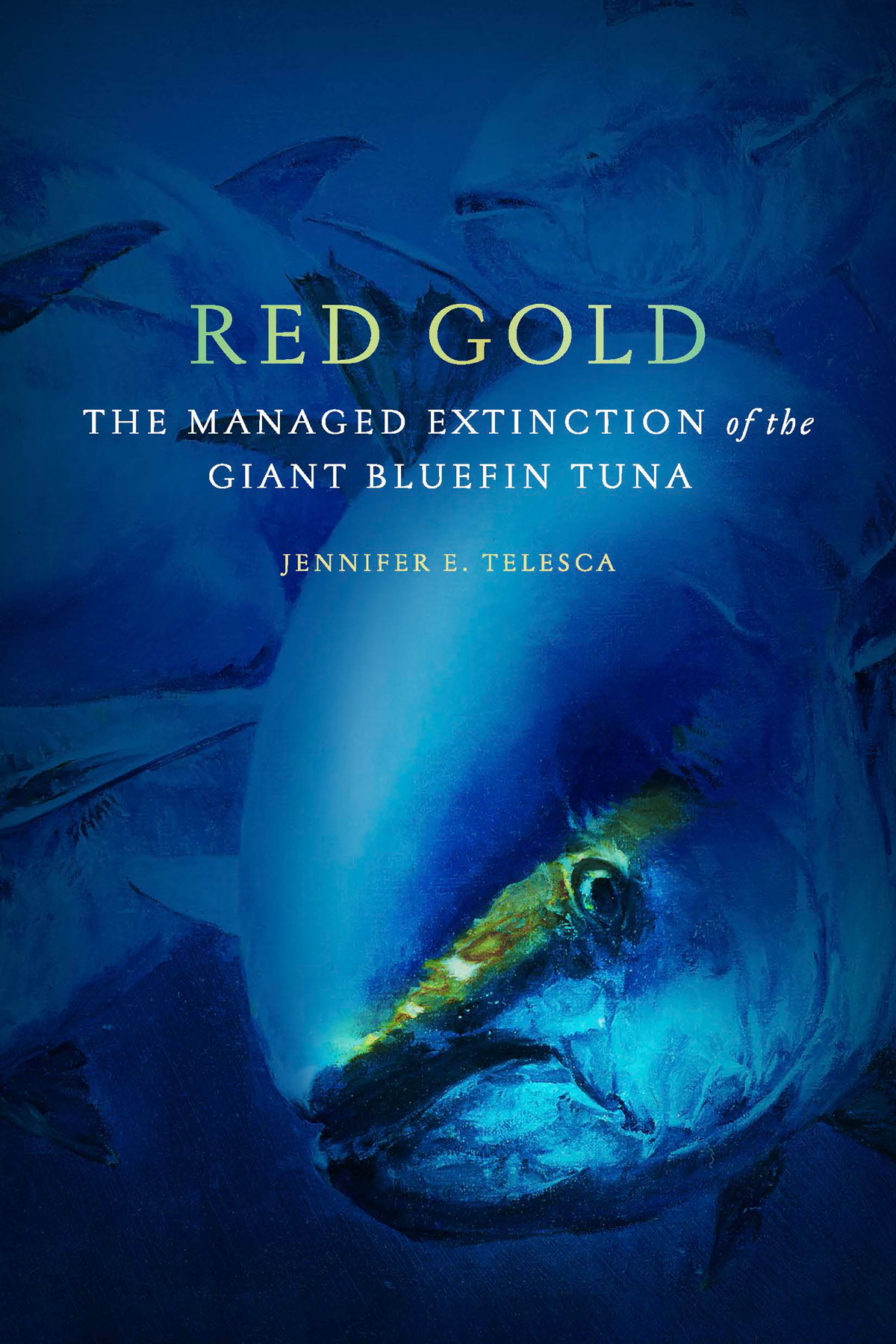

Jennifer E. Telesca, PhD

School Of Liberal Arts And Sciences, Social Science and Cultural Studies

The International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) is the world’s foremost organization for managing and conserving tunas, seabirds, turtles, and sharks traversing international waters. Founded by treaty in 1969, ICCAT stewards what has become under its tenure one of the planet’s most prominent endangered fish: the Atlantic bluefin tuna. Called “red gold” by industry insiders for the exorbitant prize her ruby-colored flesh commands in the sushi economy, the giant bluefin tuna has crashed in size and number under ICCAT’s custodianship.

Eleonora Del Federico

School Of Liberal Arts And Sciences, Mathematics And Science

Egyptian Blue is the oldest synthetic blue pigment first prepared by the ancient Egyptians around 2800 BCE. Its use became widespread as the main blue in ancient Mediterranean art but mysteriously disappeared during the 3rd century CE.

Amy Guggenheim

School Of Liberal Arts And Sciences, Humanities and Media Studies

The Vision Room is an intimate global incubator for artists, designers, and theorists to nurture inquiry, transformative interdisciplinary exchange, and the seeding of new work informed by artistic innovation, intellectual rigor, and social engagement in response to the times.

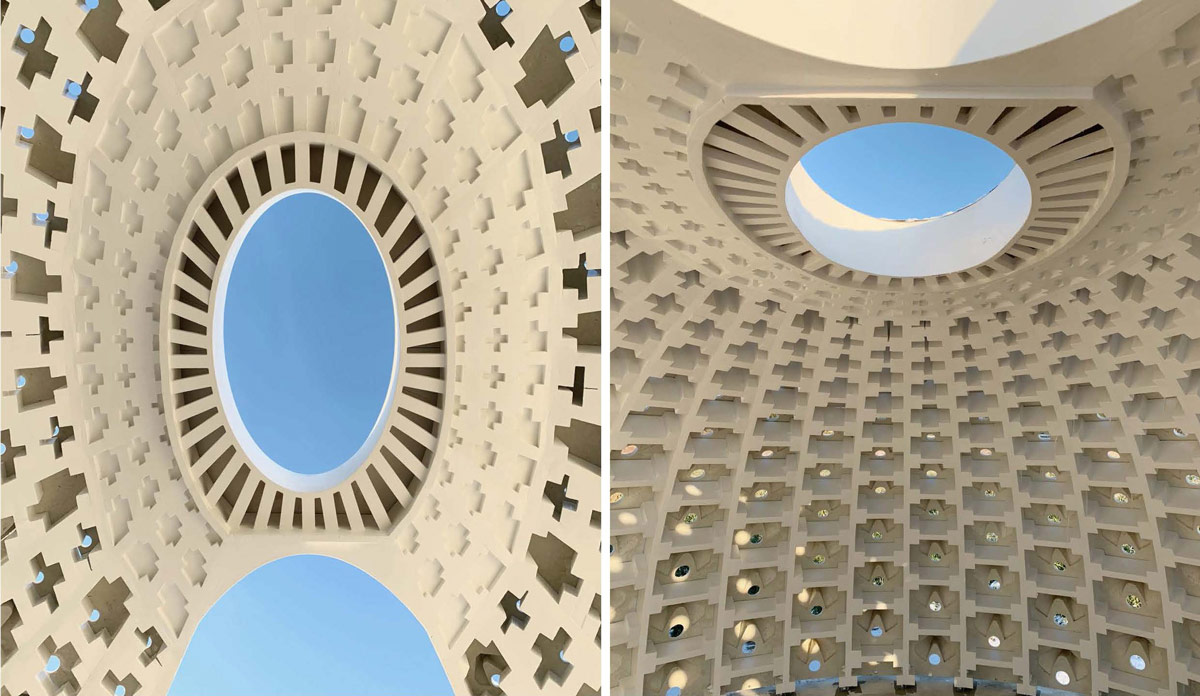

Martha Wilson

School Of Liberal Arts And Sciences, History of Art and Design

Seed Grant 2019-2020

Aeroponic Aggregates is a meditation on the role of masonry construction within contemporary building culture by re-examining the volumetric nature of the brick for its capacity to sustain biological life.

Mark Rosin

School Of Liberal Arts And Sciences, Mathematics And Science

Understanding STEM Identity explores how scientifically underserved people—those who feel like traditional access points to science like museums, newspapers, and documentaries are not for them—can become empowered to engage with science, and in turn, enrich their lives.

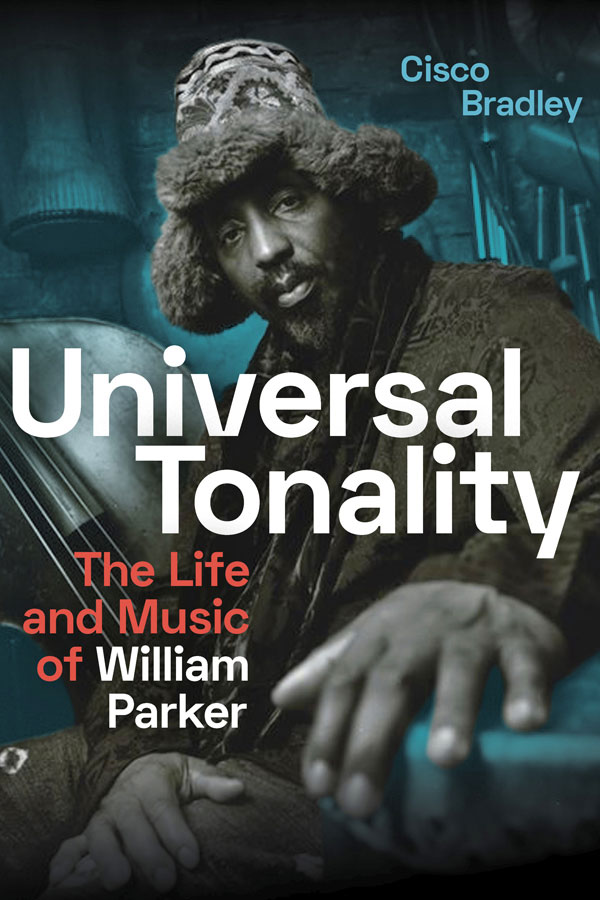

Francis ‘Cisco’ Bradley

School Of Liberal Arts And Sciences, Social Science and Cultural Studies

Since ascending onto the world stage in the 1990s as one of the premier bassists and composers of his generation, William Parker has perpetually toured around the world and released over forty albums as a leader. He is one of the most influential jazz artists alive today.

In Universal Tonality historian and critic Cisco Bradley tells the story of Parker’s life and music. Drawing on interviews with Parker and his collaborators, Bradley traces Parker’s ancestral roots in West Africa via the Carolinas to his childhood in the South Bronx, and illustrates his rise from the 1970s jazz lofts and extended work with pianist Cecil Taylor to the present day.

Jonathan A. Scelsa

Provost

As an outward-facing research center of Pratt Institute, the Consortium for Research & Robotics engages in innovative design research using frontier technologies. We work with communities and organizations that benefit from access to extraordinary technology for research, including NYC’s largest industrial robot.

Eve Baron

Gopinath Gnanakumar Malathi

Rachel Ko

Can Sucuoglu

SAVI (Spatial Analysis and Visualization Initiative) and School of Architecture, Graduate Center for Planning and the Environment (GCPE)

Children and youth have the potential to act as accumulators and distributors of knowledge in a way that other age cohorts cannot. Participatory planning processes designed to capture this potential and engage youth and children in community decision-making, not only orient the planning outcomes towards the actual needs and interests of the community, but also foster civic-minded future leaders through an opportunity to practice democracy.

Leslie Roberts

Provost, Foundation

My paintings investigate ephemeral language and rule-based abstraction. I compile lists of contemporary vernacular from the flow of information coursing through our lives and across our screens. The lists are artifacts of my social, political, and personal environment; I chart them into pattern-like works that are diagrams of their own making. These intensely chromatic, annotated panels could be called illuminated lexicons of 21st century life.

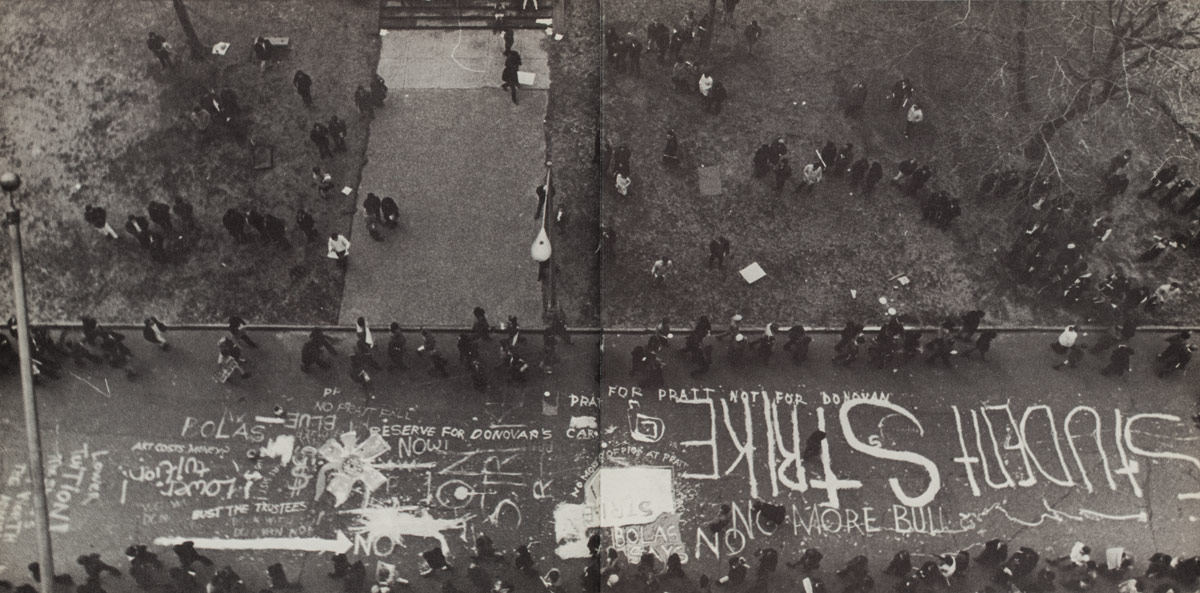

Heather Lewis, School of Art

Cristina Fontánez Rodríguez, Pratt Institute Library

Rebecca Krucoff, School of Art and School of Architecture

Keena Suh, School of Design

Vicki Weiner, School Of Architecture

Amber Colon, BFA Communications Design ‘23

Anisha Kar, MS Historic Preservation ‘21

The interdisciplinary Preserving Activism project team conducts historical research that seeks to foster public dialogue about social justice activism between and beyond Pratt’s gates. This past year faculty and students worked with the Institute Archivist to examine 20th century activism at Pratt through coursework and the collection of oral histories, texts, and ephemera that will become part of the Archives.

Can Sucuoglu

SAVI (Spatial Analysis and Visualization Initiative)

Understanding the changing conditions of the Hudson River and its Estuary requires a complex set of indicators. The water quality, health of fish and wildlife, amount and location of public access, and engagement of residents in stewardship activities tell us about these ecosystems and management needs.

Carolyn Shafer

Pratt Sustainability Center

The Pratt Sustainability Center has developed a suite of sustainable materials research resources to provide Pratt’s students with the tools they need to critically consider the impacts of the materials that they use. By training and educating future leaders, scholars, designers and artists, Pratt is uniquely positioned to prepare our students to understand and address sustainability challenges. As we continue to offer sustainability resources specific to the needs of artists and designers, the Pratt Sustainability Center is helping to equip our students to lead our society to a sustainable future.

The mission of the Office of Research and Strategic Partnerships is to foster new and exciting research opportunities for faculty, staff, and centers at Pratt Institute, and to help make connections with each other, as well as industry and community partners beyond the gates of the Institute.

The Pratt Research Talks began in 2019 as a collaboration with the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) and our Research Brown Bag Lunch Series. Throughout the semester, we met in person for an informal presentation and discussion during lunch, where presenters from across the schools, as well as the provost centers, shared their research and answered questions. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit our world and our office began work remotely, we wanted to continue these talks as a way to connect and inspire researchers through sharing the incredible work people at Pratt Institute do everyday.

We expect to continue offering these talks, and are currently curating our fall series. If you are interested in presenting, or think someone you know would be great for our series, please get in touch via research-partnership@pratt.edu.

“THE DESEGREGATION THINK TANK”

Jerrod Delaine

The Desegregation Think Tank is an advocate for change in housing policy. In America, federal/state/local housing policies and incentives have created and maintained segregated communities. This collective analyzes the systems impairing communities and provides solutions that will lead to better communities for all Americans.

Bio

Jerrod Delaine is an experienced real estate developer as well as designer and builder. He’s a currently a professor at Pratt Institute.

“ANIMAL-COMPUTER INTERACTION AND THE CASE OF THE DISAPPEARING BEES”

Nancy Smith

This talk will explore key ideas in the emerging field of animal-computer interaction, and the ways in which our technologies are increasingly involved in the lives of animals. This creates both challenges and possibilities around sustainability, conservation, and animal wellbeing. I will share a particular case study around my research with bees, and will highlight some of the ways I have been thinking about animals and design.

Bio

Nancy Smith is an Assistant Professor in the School of Information, where she teaches in the Information Experience Design Program. Her primary research is focused on understanding the relationship between digital technologies and the environment, which includes work in sustainability, environmental justice, and speculative design. She has a Ph.D. in Human-Computer Interaction from Indiana University.

“SUSTAINABILITY TOOLS FOR CULTURAL HERITAGE PRESERVATION”

Sarah Nunberg

Life cycle assessment has been a valuable tool for architects, engineers, and industry in evaluating the environmental impact of materials and actions from cradle to gate and cradle to grave. In 2019 the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works was awarded a National Endowment for Humanities grant to develop an LCA tool populated with materials used by custodians of cultural heritage and a library of case studies examining actions carried out in cultural heritage preservation. The grant team is composed of Northeastern University engineering students led by professor Matthew Eckelman; Pratt Institute communication design graduate students and professor, Eric O’Toole; and conservation students and professors from graduate programs at NYU, UCLA, University of Delaware, and State University of Buffalo. This talk will summarize the goals of the project and describe the work carried out to date.

Bio

Sarah has been working in private practice as an objects conservator in Brooklyn NY since 2006. Starting in 2012 Sarah began to research sustainable practices and life cycle assessment through her work with the American Institute for Conservation Sustainability Committee. In January 2020 she and her co-Principal Investigators from Foundation for American Institute for Conservation, Northeastern University, and Sustainable Museums were awarded a Tier II Research and Development Grant to fully develop a life cycle assessment ( LCA) Tool and Library. As a visiting professor at Pratt Institute she teaches an undergraduate course on in the Math and Science Department on material degradation and an Art History Master’s course in the ethics of conservation. Sarah received her advanced certificate in conservation and her MA in Art History from the Institute of Fine Arts Conservation Center at New York University in 1994 and her MA in Archaeology from Yale University in 1990.

“PARTICIPATORY RESEARCH & EATING TOGETHER AGAIN”

Amanda Huynh

Social Practice Kitchen is a mobile kitchen, designed to be a site of interdisciplinary investigation across the School of Design. Using food as both a material and tool for communication allows for an exploration on the topics of food waste, cultural impact, community building, social innovation, food security, and service design. This talk will link the Social Practice Kitchen with another on-going project about co-designing together while physically apart.

Bio

Amanda Huynh, Assistant Professor of Industrial Design, Pratt Institute works at the intersections of community-building, social innovation, and sustainable design.

“SOUND PEDAGOGY: SOUND ART AND SOUND INSTALLATION”

Daniel Bergman and Ilayda Altuntas

This collaborative research project between Ilayda Altuntas of Penn State University and Pratt’s Center K-12 is designed to assess the impact of curricula that invite New York City youth to express and explore their identity, language, and socio-cultural backgrounds using the methods of listening, producing, and recording the sounds of their own choice of environments. Through this research, we aim to meaningfully contribute to art education by exploring the meaning of silence, noise, and rhythm from environmental sounds. The sound art program consists of ten sound art lessons for 9-12 grades and focuses on creating sound art pieces using a wide range of materials, including string, wire, mini-electric motors, rubber bands, ping pong balls, balloons, and wooden sticks, inviting students to explore sound and place.

Bio

Ilayda Altuntas is a 4th-year Ph.D. Candidate in Art Education with a minor in Curriculum and Instruction at Penn State University (Bunton Waller Award Recipient). She currently serves as co-president of the Graduate Art Education Association and as a Graduate Teaching Assistant on ART 20: Introduction to Drawing. Her dissertation focuses on a sound curriculum called “Tuning in NYC for Art Education”, a teaching resource focusing on experiencing, creating, and composing soundscapes of environments.”

Daniel Bergman is the Director of Pratt’s Center for Art and Design Education and Community Engagement, K-12. Prior to coming to Pratt, he has had a career as a K-12 arts educator and administrator in schools, non-profits and museums. He has a B.A. in Visual Art and Intellectual History from Wesleyan University, M.F.A in Painting and Sculpture from S.V.A and an M.S Ed in Educational Leadership from The University of Pennsylvania.