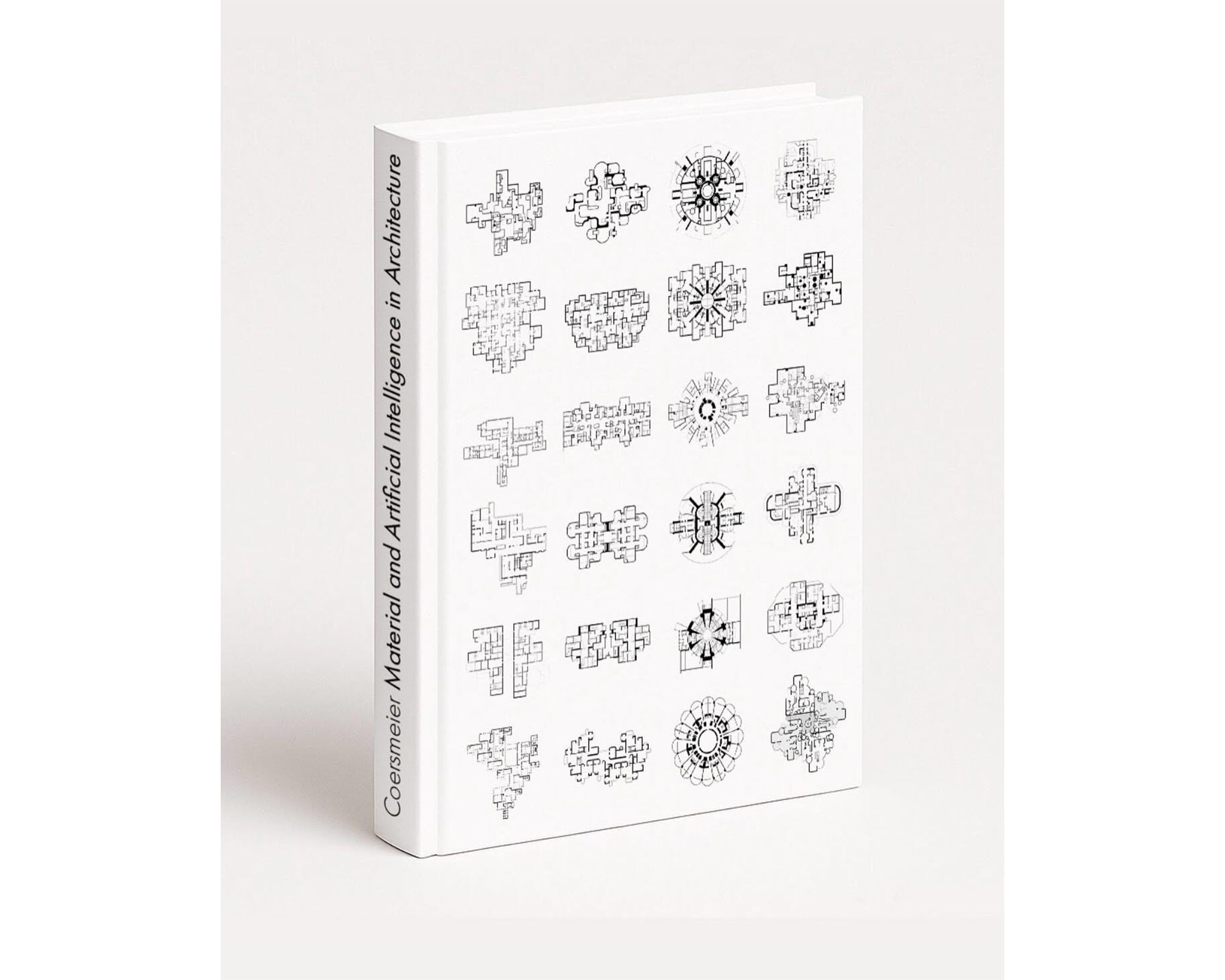

How will our built environment change when designed more and more through the visions of machines? Artificial intelligence (AI) has a history in programming that predates its now ubiquitous presence in culture, yet it’s only in the past few years with widespread access to chatbots and generative image programs that many people have directly interacted with it in their creative work. Although almost every field is grappling with the implications, ethical dilemmas, and possibilities of AI, architecture faces particular challenges and opportunities in adapting its design processes to this technology.

Digital imaging has long been central to communicating ideas in architecture, acting as an intermediary between conceptual forms and the built world. Architects are now considering not solely how to use AI to automate aspects of their work, whether workflows or as a way to efficiently interpret regulations like building codes, but also how it can be a tool of creative collaboration as they experiment with a technology that is still evolving.

A study released this year by the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in collaboration with Deltek and ConstructConnect found that while just 6 percent of architects surveyed are regularly using AI tools in their work (including chatbots, image generators, and tools for analyzing grammar and text), 53 percent have experimented with AI, suggesting a modest but growing level of adoption as questions about its usage remain. Around three-quarters of the architects reported feeling optimistic about AI’s potential to automate manual tasks, yet a whole 90 percent had concerns about AI’s inaccuracies, security, authenticity compared to purely human-made work, transparency, and how its data and models might be used.

Meanwhile, the 2025 AI report from the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) stated that 59 percent of its surveyed architects’ practices are using AI, up from 41 percent in 2024. It is likely these numbers will climb in the coming years as understanding about what AI can do and how architects could use it further develops.

“It’s changing every day because all of the AI models that we’re all using, they’re learning,” said Jason Vigneri-Beane, professor of undergraduate architecture in Pratt Institute’s School of Architecture. “Whatever is happening now is never going to happen again, because it’s not like normal software where you open it, you use it, you close it, you open it the next day, and it’s the same. Neural networks are learning, and so you can generate something, and then an hour later, they learned so much from all the other people using it, that moment is gone.”

It was with this interest in capturing the current experimentation with AI and architecture that Vigneri-Beane cocurated Transductions: Artificial Intelligence in Architectural Experimentation with Olivia Vien, MArch ’15, adjunct assistant professor in Graduate Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and Urban Design (GALAUD) at Pratt; Stephen Slaughter, chair of undergraduate architecture; and Hart Marlow, MArch ’09, interim assistant chair of GALAUD. The exhibition, held in early 2025 at The Rubelle and Norman Schafler Gallery on Pratt’s Brooklyn campus, included over 30 architects and designers working in architecture at Pratt and beyond and showcased what they were at that time exploring with AI in their work. It wasn’t an exhibition merely speculating on the future of AI but instead examining how early adopters have already been pushing the technology to its limits.

“One of the things that prompted the show was following the explosion of experimentation around generative AI and its new visual possibilities,” Vigneri-Beane said. Themes that emerged when the curators were viewing the work together revealed how lines were blurring between the physical and virtual, with AI encouraging hybridization between the two by bringing in source material not only from architecture but also from areas such as ecology and geology or film and art.

While architects can input constraints, design styles, specifications for materials, types of buildings, and other guidelines into text-to-image machine-learning models like Midjourney and Stable Diffusion, what these models generate can often be a surprise as they turn text prompts into visuals based on things like patterns in their datasets. Architects are also inputting their own renderings or sketches into these models and further augmenting them through prompts, opening up new directions that they may not have discovered in more conventional modeling software.

“It’s very easy to get something; it’s very hard to get something interesting.”

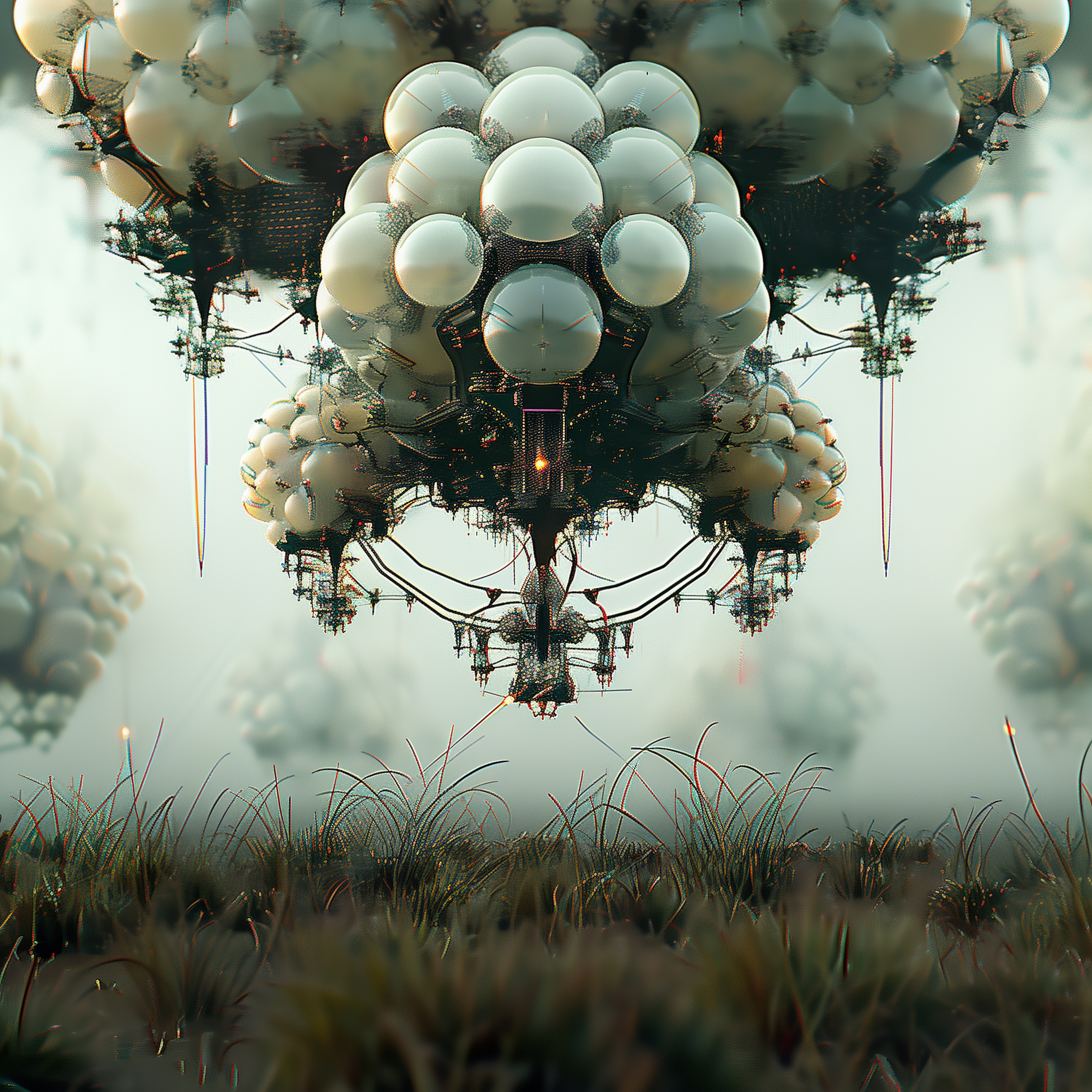

Vigneri-Beane, who is also the founding principal of the Brooklyn-based Split Studio, has an ongoing project on “cyborg ecologies” that engages with AI image generation in taking a futuristic perspective on the relationship between ecology and design at an imagined time when both are being created by machines. The images are hauntingly beautiful even with their hints of apocalypse, envisioning synthetic flowers growing on intricate structures and otherworldly floating contraptions—or “aerial infrastructures,” borrowing from the title of the work—terraforming new ground.

“It’s very easy to get something; it’s very hard to get something interesting, because the more these models learn, the more many of them are tending—because of the way that people are using them—towards realism and commercialism,” he said. He added that when he first started using AI image generators, there were a lot of what are known as “hallucinations,” when the AI would glitch away from reality to fill in the gaps or perceive patterns or objects that were not there. “It was really hard to get something reasonably representative, and now it’s flipped. It feels like you have to work harder every week to uphold the creativity, which I think is a good argument for why we’re vital contributors to this process.”

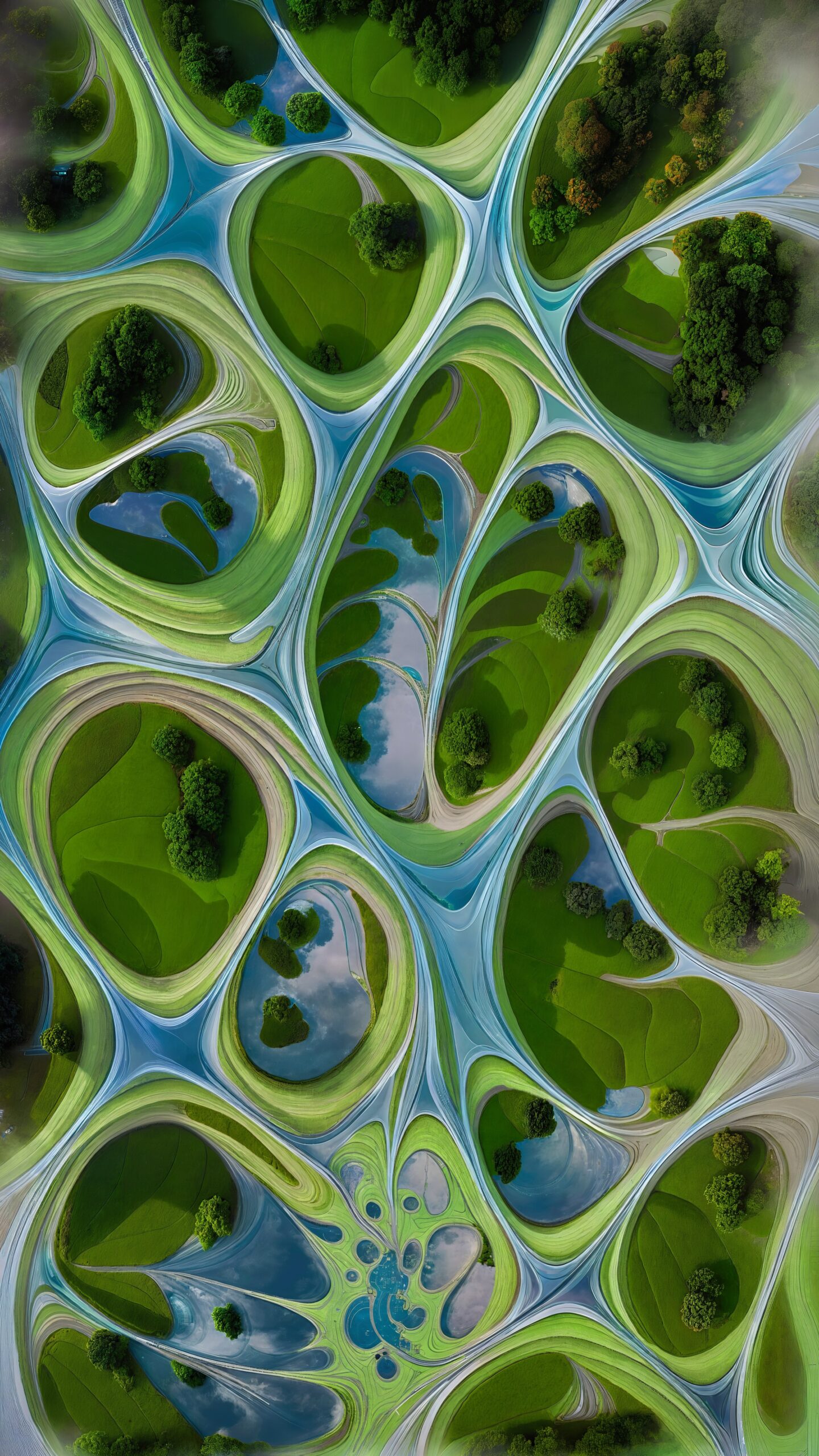

Indeed, many of the creators featured in Transductions emphasized that human intervention is still necessary in these digital processes. “We have to understand what [AI] is capable of, but we also need to understand how to use it, and then how to break it or how to manipulate it and use it with intent,” said Alex Tahinos, adjunct assistant professor in GALAUD. His work featured in Transductions challenged the way that AI tends to be object-oriented and focused on the foreground of its generated images. He instead aimed to make the architecture itself a landscape of structures seemingly being absorbed into the environment, a concentration on the background of a rendering that is contrary to how AI is usually viewing architecture, as it privileges a building or structure rather than its context.

Tahinos is the founder of the multidisciplinary practice fka design and has an ongoing interest in creating hybrid environments through experimenting with technology. His work in Transductions, in bringing building types into unexpected collisions of styles and forms, also expressed how AI creates images that are guided by the relationships between the vast data it is drawing on, which come from diverse visual sources.

“One of the biggest things that needs to be discussed when it comes to AI is the culture of, for lack of a better term, sampling,” Tahinos said. “The music industry went through this same thing, and I think now with the influx of all these images, this tool becomes our way into that idea of sampling, and I think that we’re going to have very similar discussions over the next years based on authorship.”

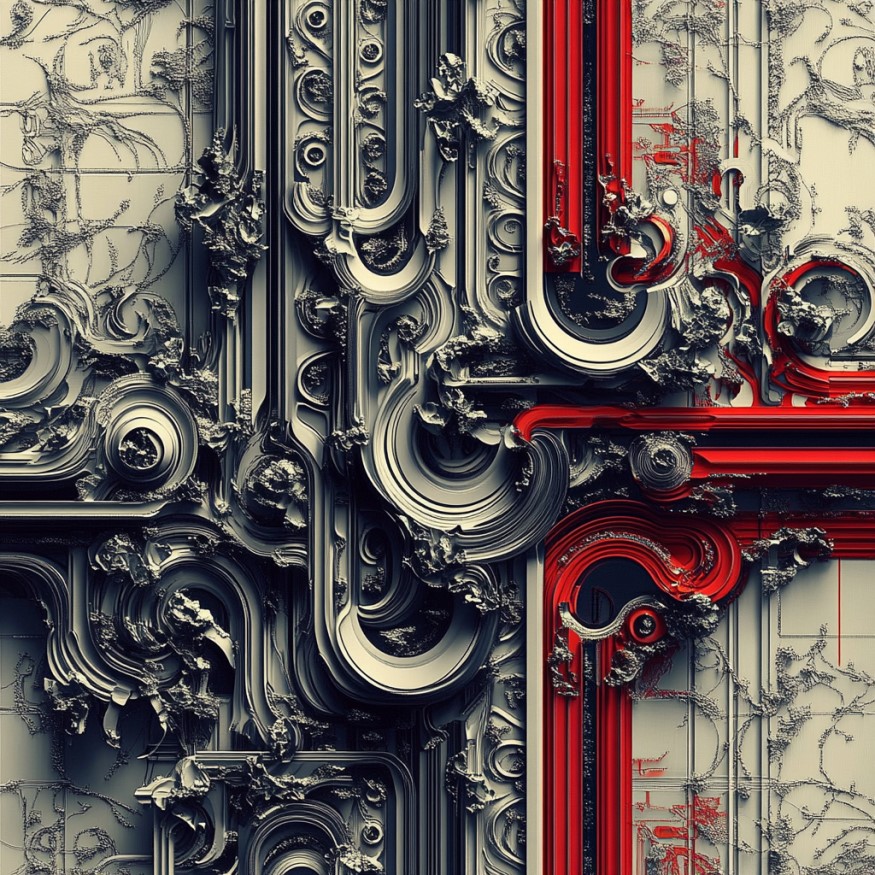

Where the architect fits as an author in the creative process when AI is a part of it was also a recurring theme in Transductions, including in more practical considerations of its role in making real-world objects. “I see it as a powerful extension of existing workflows, a tool to accelerate iteration and bridge the gap between digital design and physical fabrication,” said Robert Lee Brackett III, adjunct associate professor of undergraduate architecture.

He noted that his practice already merges hands-on techniques like model-making and sketching with computational methods, such as simulation and 3D printing, with AI adding another connection between those tactile and technical approaches. “The key is utilizing AI not as an autonomous creator, but as a collaborative partner, reacting to and enhancing human intention, responding to established design parameters, and accelerating the translation of ideas into tangible form.”

Brackett’s work in Transductions demonstrated how he has been translating abstract, textured landscapes digitally made with AI into 3D forms that are then milled into foam and cast in concrete. Like Tahinos, he has been confronting the limitations of the dominant perspective of AI as it tends to veer towards photorealism rather than abstraction. Transductions also featured Brackett’s work with Duks Koschitz, professor of undergraduate architecture, with whom he codirects d.r.a. Lab (Center for Design Research in Architecture) at Pratt. They have been investigating the use of AI to generate images of inflatable structures—something they’ve regularly utilized, as pneumatic structures offer quick and cost-effective solutions for large temporary works—with a concrete texture.

“This probably took longer than making a 3D model and using standard rendering tools, but the form was imaginary, and we wanted to push the tool,” Brackett said. While inflatable concrete might seem like an impossible idea, attempting to make a heavy material into something ephemeral and light, Brackett and Koschitz are interested in how AI is allowing them to realize what would be too difficult to test only through hands-on building. “It’s a constant feedback loop—taking things from the physical world, putting them into the digital world, generating plausible scenarios, and then bringing that back out to see if we can make them at the scale of architecture.”

This fall, Brackett and Koschitz are teaching an undergraduate advanced design studio exploring generative AI outputs, including image and text generation as well as 3D modeling, in which students will be asked to integrate AI tools into an architectural workflow. With the wide availability of AI, both undergraduate and graduate students are often coming into their courses with some firsthand knowledge of what the tools can do by having interacted with text-to-image models like DALL-E, which was released in 2021, and Stable Diffusion and Midjourney, which were both released in 2022. The dialogue that many educators are hoping to start in introducing AI to their coursework is in asking students not to take the outcome of AI image generation as the final product and instead use it as a starting point or sandbox for their individual creativity.

“The point is to try to teach them that no matter what the tool is, your job and your agency as a designer, as an architect, should be to bring your own thoughts and ideas to it and never let the tool just tell you how to use it,” said Caleb White, visiting assistant professor in GALAUD. “And I think we’ve learned that from years before dealing with digital tools in architecture.”

-

![An AI-generated image of an inflatable concrete structure made of ribbed tubes over a manmade pond surrounded by trees.]()

-

![An AI-generated image of a cavernous, inflatable concrete structure over a lake surrounded by fall foliage.]()

-

![An AI-generated image of an round inflatable concrete structure made of ribbed tubes on a platform beside a manmade pond.]()

-

![An AI-generated image of an inflatable concrete structure with many openings over a manmade pond surrounded by trees.]() Duks Koschitz and Robert Brackett III, Inflatable Concrete Pavilions (Series), 2024

Duks Koschitz and Robert Brackett III, Inflatable Concrete Pavilions (Series), 2024

He pointed out that modeling programs like AutoCAD have been a standard of 2D and 3D computer-based design for architects since they were introduced in the mid-1980s. While AI can represent a new frontier of design possibilities, it still requires the same level of awareness of how the technology works and how it can be used to express an idea and still bring a level of craft to its image production, just as an architect wouldn’t take the default tools of another rendering software as their final product.

White, who is also a lecturer in Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s School of Architecture and cofounder of the architectural design firm MatterLab, based in Troy, New York, and Mixed Signal, an experimental design media group, has been engaging with AI in his work for years before its increased accessibility. He brought that experience into the Mediums 3-Visualization course he cotaught with Ramon Pena Toledo, visiting professor in GALAUD, and Joseph Giampietro, adjunct assistant professor in GALAUD.

“There are certainly experts in the industry on AI, but I would actually say that most of us are amateurs and playing with it together,” White said. “So we tried to take that position in Mediums. We wanted to incorporate AI because you can’t ignore it anymore. It’s important for students to be exposed to these tools, but we also didn’t want it to be an AI-focused seminar, because I think everybody is realizing this tool can become a little bit of an echo chamber, and it can actually start to limit the outputs that you can achieve if everyone’s using the same tools in the same ways.”

That concern with the sameness of AI content is not unique to architecture, with everything from the use of ChatGPT for writing to the uncanny perfections achieved by AI photo editing tools threatening to homogenize creative work. Likewise, AI’s environmental impact, its privacy concerns, copyright issues, and ethical questions about the scraped data AI models are trained on and their biases are shared across disciplines engaging with this technology. Job displacement from AI—whether the technology is actually able to replace a human or if doing so seems economically advantageous for the employer—is also shadowing excitement about applying it to practices and firms in architecture, where positions that are between the creative process and production have the most precariousness in being taken over by AI through automation.

“AI is fundamentally changing how people work and is likely to replace some jobs,” said Mark Heller, an assistant professor in the Master of Landscape Architecture (MLA) program. “In the short term, there may be a risk of layoffs and downsizing as firms compete to be the nimblest. In the long term, I am hopeful there will be a flourishing of small landscape architecture studios—individuals, partners, small collaboratives, possibly even guilds, that are able to compete with traditional firms because they develop unique and efficient modes of leveraging AI.”

Heller’s work includes building software for landscape and urban analysis, modeling, and simulation, and while he said he has used AI minimally, it’s been in a range of applications, from the most basic, as a thesaurus, to more complex usages like identifying best practices and precedents. He compared it not to replacing a person but instead to the need to pull up a dictionary or scroll Reddit threads for information.

“Optimistically, the potential of any new tool is to free us from drudgery,” Heller said. “Architecture and its allied disciplines are heavily mediated by software. If automated workflows and more intelligent software and hardware can shift the balance between computer-based time and time spent in the field with real materials—not proxies—the most important question to entertain is how we want to spend that newly available time.”

It also has the potential to create new roles in the industry, notably in construction, which works in partnership and alongside architecture. For example, Vardhan Mehta, BArch ’18, was recently named to the “Forbes’ 30 Under 30” list for his work as the cofounder and CEO of Acelab, a Brooklyn-based company established in 2020 that is creating AI-powered software that can support construction companies in sourcing sustainable and affordable building materials. As more architects start looking into how to use AI, more opportunities will presumably arise, whether it’s analyzing risk factors in the structure of a building or improving a design’s sustainability by testing different layouts. (Being able to give text-to-image generators a prompt that actually creates something that stands out from the rest of AI-generated imagery, meanwhile, is a new and necessary skill in itself.)

“The question is not will we adapt, but who will script the adaptation.”

“Every generation, across all disciplines and professions, contends with the possibility of professional extinction. But architecture doesn’t die—it mutates,” said Dr. Harriet Harriss, professor in the Graduate Center for Planning and the Environment (GCPE). “When drawing boards gave way to digital modeling in the 1980s, the discipline didn’t collapse; it recomposed itself. Each technological rupture is less an ending and more an invitation. The question is not will we adapt, but who will script the adaptation. Enter early, and we write the spatial syntax of tomorrow’s cities and spaces; enter late, and we become footnotes in someone else’s dictionary. Architectural pedagogy should not attempt to protect students from this disruption by persisting with a business-as-usual approach, but instead should apprentice them into disruption—teaching them to choreograph the ruptures rather than merely withstand them.”

Those consequences are incredibly evident in the many criticisms of AI, such as its tendency to elevate certain perspectives and dismiss others, and how it can amplify any biases that were part of the data it was trained on. Especially since that data has largely been scraped from the internet, it has taken in all of the discrimination, stereotypes, and inequalities in who and what are represented there and how.

Studies of text-to-image AI systems have revealed that they can reinforce and perpetuate stereotypes about gender and race and foreground a Western cultural perspective. Likewise, architecture by the leading designers of the United States and Europe is more likely to be in the datasets than architecture originating in parts of the world that are underrepresented online. According to the nonprofit Internet Society, over half of online content is in English, although approximately 16 percent of the global population speaks English as a first or additional language, further skewing what content is shaping the output of AI.

“AI is no oracle. It is a mirror, smeared with the fingerprints of its makers,” Harriss said, recalling themes explored in Preservation in a Time of Precarity, a Pratt symposium “on the intersection of, and equanimity between, artificial intelligence and Indigenous intelligence” held in fall 2024. “Its training sets are already biased towards Western and Global North assumptions and advantages. If we let those values dominate, AI becomes not a tool of possibility but a repetition engine for old hierarchies, including gender and racial biases that are often dressed up as ‘traditions.’ That is why pedagogy must teach students not just how to use these tools, but how to disobey them—how to imagine against the predetermination and often prejudice of the prevailing datasets.

“What should give us all hope,” Harriss added, “is the impact that the extraordinary diversity of the next generation of architects is beginning to have on AI. They are not just inheriting it, they are shaping it, embedding new forms of ethics, justice, and ecological responsibility into the datasets and the design cultures that AI learns from and carries forward. That’s the essence of machine learning: it absorbs the identities of those who train it. Consequently, a leading architecture school is less a site of instruction and more a rehearsal space for futures that do not yet exist—a place where students learn to teach the machine as much as it teaches them.”

This is probably simply the beginning of how AI will shape the practice of architecture, as much of what has been most visible are those stunning and strange renderings of fantastical structures that merge data culled from across human culture into new forms. Architects have never taken just one approach to how they represent their work, even in the days of sketches and models, and for many, AI is another avenue for this visualization that at the same time can encourage them to rethink their ideas by doing something unexpected. As architects are exploring its potential for imagery, design, and automation, they are finding new ways to create while making sure that the world AI is envisioning is one that keeps humanity at its core. ![]()

The imagery in this story, the work of Pratt Institute faculty and their collaborators, was featured in the 2025 School of Architecture exhibition Transductions: Artificial Intelligence in Architectural Experimentation.