“One way to stop seeing trees, or rivers, or hills, only as ‘natural resources,’ is to class them as fellow beings—kinfolk,” Ursula K. Le Guin writes in the preface to her poetry collection Late in the Day. “I guess I’m trying to subjectify the universe because look where objectifying it has gotten us.”

Le Guin’s proposal for reorienting perspective is one of the entry points that Adjunct Professor (CCE) Jean Brennan and Adjunct Assistant Professor Maria Gracia Echeverria share with their students in the MFA Communications Design Cross-Disciplinary Studio—Symbiotic Futures, a class that calls them to examine their relationship with the world through new ecological lenses. In the studio, communications design connects with a range of other creative practices and areas of study, creative research moves away from the screen and into the field and extends across the senses, and, uniquely, nonhuman beings become collaborators.

The course is derived from curricula that Brennan and Echeverria developed separately, in 2020 and 2021. The realization of their shared interest in forming a cross-disciplinary curriculum that integrates environmental art and the humanities with design led to Symbiotic Futures. As they looked at big-picture themes that thread through the work happening at Pratt, like sustainability and climate change, Brennan and Echeverria wanted to create a space that wasn’t so much about identifying and fixing a problem but prompting a “leap of imagination,” as Echeverria puts it, and “reconnecting to who we are as animals, and who lives with us, our neighbors—and allowing them to change you.”

It is a more philosophical angle on ecology, Brennan says, than the approach students take in courses like Sustainability and Design, which she also teaches. Moving through three exploratory phases, or modules, of the class, students in the Cross-Disciplinary Studio will tune into their own place in nature and then research a specific being—moss, a mushroom, an octopus, a tree—learning its origins, habits, relationships, and ultimately co-create something with them. The idea is not about mimicking another living thing, Brennan emphasizes, but “becoming inspired by their way of being as a point of reference for making.” For students, it’s an opportunity to focus attention on other ways of living and creating, practice new modes of working, and open up to ways of seeing the world that could carry into any kind of future work.

We Are Part of Nature Everywhere

The first module of the course, called Entanglement, grounds students in the experience of place, as they embark on field research in their urban environs around Pratt. A vacant lot, a sidewalk tree plot, or their apartment backyard might contain a “novel ecosystem,” a term from the book Rambunctious Garden by Emma Marris that refers to new ecosystems that come about due to human intervention. The students look at their environs through the eyes of a researcher, engaging other senses as well to notice and connect to their surroundings. “Field work” is how Brennan describes the process, which includes collecting, drawing, writing, and collage.

Meanwhile, students are considering Indigenous thinking about land and kinship, looking at artwork like Cy Twombley’s Natural History, Part I, Mushrooms and Uta Barth’s photography exhibition to walk without destination and to see only to see, and learning about composer Pauline Olivaros’s practice of “deep listening.” An embodiment workshop has students interact with just some of the guest artists and thinkers the studio faculty host throughout the semester, to do awareness-building exercises.

The culmination of the module is what the professors call “a polyphonic assemblage,” a reference to a concept by anthropologist Anna Tsing related to how human- and nonhuman-made worlds intertwine. All eight sections of the studio put up their work, artifacts, and observations from the field research for everyone to see—many students experimenting with form, with video, installations, printed matter, and other mediums appealing to all the senses to build a story.

A New Colleague

In the Ontology module of the class, students choose a being to research and ultimately collaborate with, something they’ve connected with on an intuitive level. Over the several years the course has run, students have looked at species they live with every day, reached back into family history, and found organisms with unique adaptations or cultural significance. The aim is, as Echeverria says, “to go deep into the universe of this being, so you can have a thoughtful conversation with it.”

Students research the behavioral, relational, visual, and formal qualities or characteristics that define their organism, as well as the cultural and mythical narratives attributed to it. These are visually recorded and mapped in a class Miro board. The module ends with a 2D installation project that asks the students to translate a particular aspect of their organism into a visual form, to be presented at an all-cohort gathering.

This is the point, Brennan says, where the umwelt of the being—the way it experiences the world—begins to emerge for the students, and “how this way of being might suggest a methodology that they can carry into their making.”

Creating Together

The final weeks of the class are all about process, with a series of short making exercises in different mediums, from language to speculative design to performance, wrapping up with a final project (three examples of which are featured in this story). Done in collaboration with their being of choice, this module is called Sympoiesis, or “making with,” a term the students come across in their reading from scholar Donna Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble. (“It is a word for worlding-with, in company,” Haraway writes.) “For some students, their organism is a jumping-off point for new ways of seeing, for others it provides content for speculative storytelling, still others find methods to ‘invite’ their organism into a kind of collaboration as a fellow design colleague,” says Brennan. Encouraging them to explore the complexities of those relationships and less obvious conceptual pathways, Brennan and Echeverria have seen their students start to experiment more, to broaden their creative boundaries.

One student in 2024, Frieja White, MFA Communications Design ’25, who chose a fly for her final video-installation project, reflects on how those investigations reoriented her practice: “[The class] helped me see how seemingly ordinary subjects, like house flies or the sounds of nature, can reveal deeper insights when explored through a creative lens,” she says. “This project also taught me to embrace interdisciplinary approaches, using concepts like cymatics to bridge sound, motion, and material in new ways, ultimately transforming how I approach both design and the creative process.”

As Echeverria says, “The class wants to show you how much you can learn from these different perspectives, to expand your vision of the world.”

Three Projects

Walnut, Juglans regia

Jose Inclán, MFA Communications Design ’25

Professor: Jean Brennan

Jose Inclán’s Cross-Disciplinary project delved into family history, with the walnut tree as collaborator. The walnut holds a deep connection to his grandfather, who grew up in the hills of northern Spain, in Asturias “colloquially called ‘the natural paradise’ of Spain, as it is full of forests, beaches, and mountains,” Inclán says. “His village was composed entirely of walnut trees.”

In his project proposal, Inclán remembers how his grandfather, who was a shepherd and then tended trees across the country for the Spanish government, acted as caretaker for a plot of land in a small village in Spain. In that plot, he planted and tended numerous species of trees where the native growth had previously been cut down for lumber.

“In 1960, my granddad planted 30 walnut trees in Spain. He showed me the passion to live with and for nature.”

During a summer visit, on one of their daily walks to the plot, he brought Inclán to his favorite tree: the walnut. It was a symbol of sturdiness as well as nourishment and care—“juglone, an allelopathic compound that inhibits the growth of species around the tree, makes it a very robust and vigorous species, but at the same time very gentle, giving us shade and an edible seed to eat,” Inclán says.

After his grandfather passed away in 2015, his family buried him on that plot of land—“a land created by nature but replanted by him to give back to the planet,” Inclán reflects in his project proposal—and they planted a walnut in that spot. “He will forever be connected to us in symbiosis with the tree. He will give us shade, nuts in the fall, and a memory of how we are one within nature.”

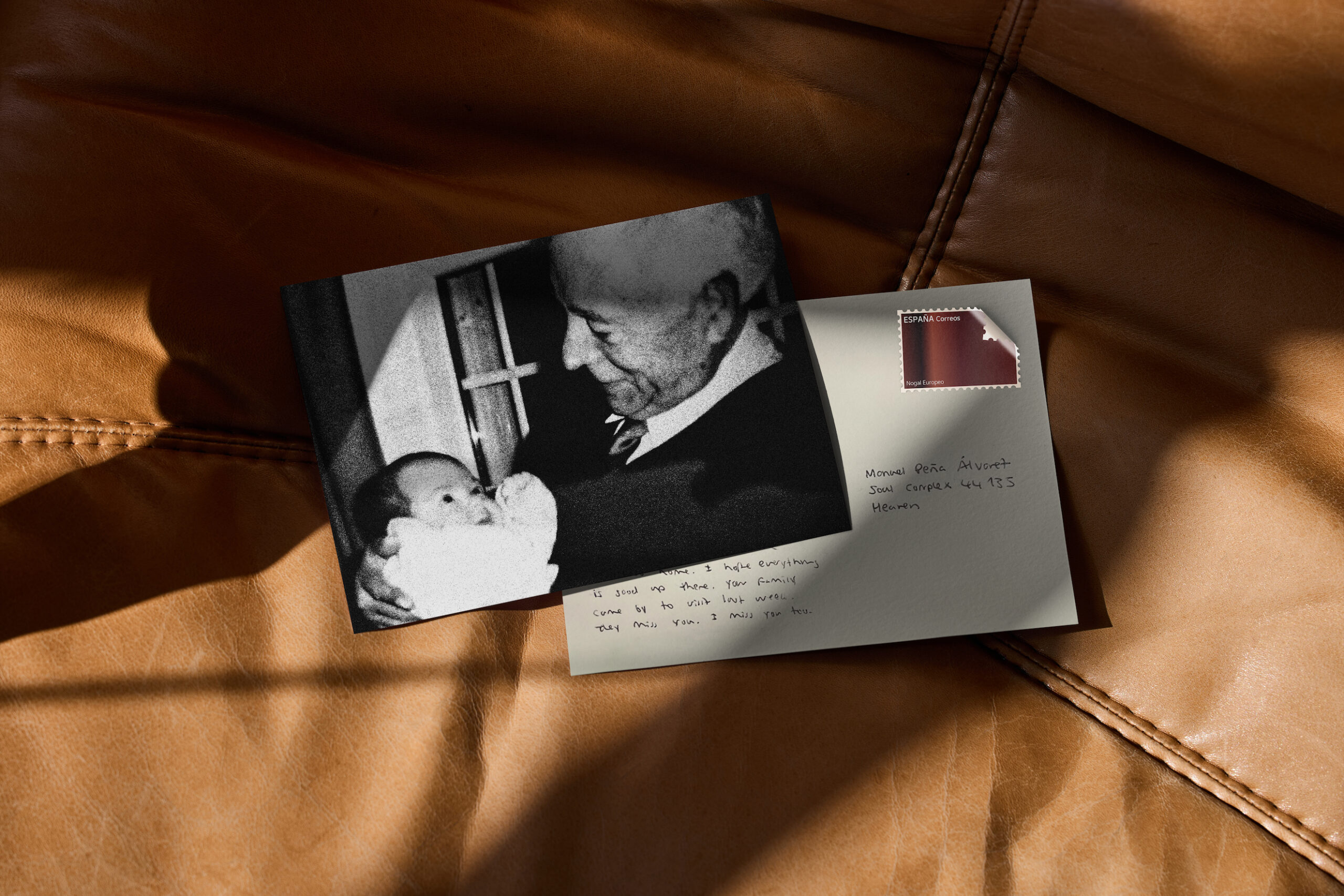

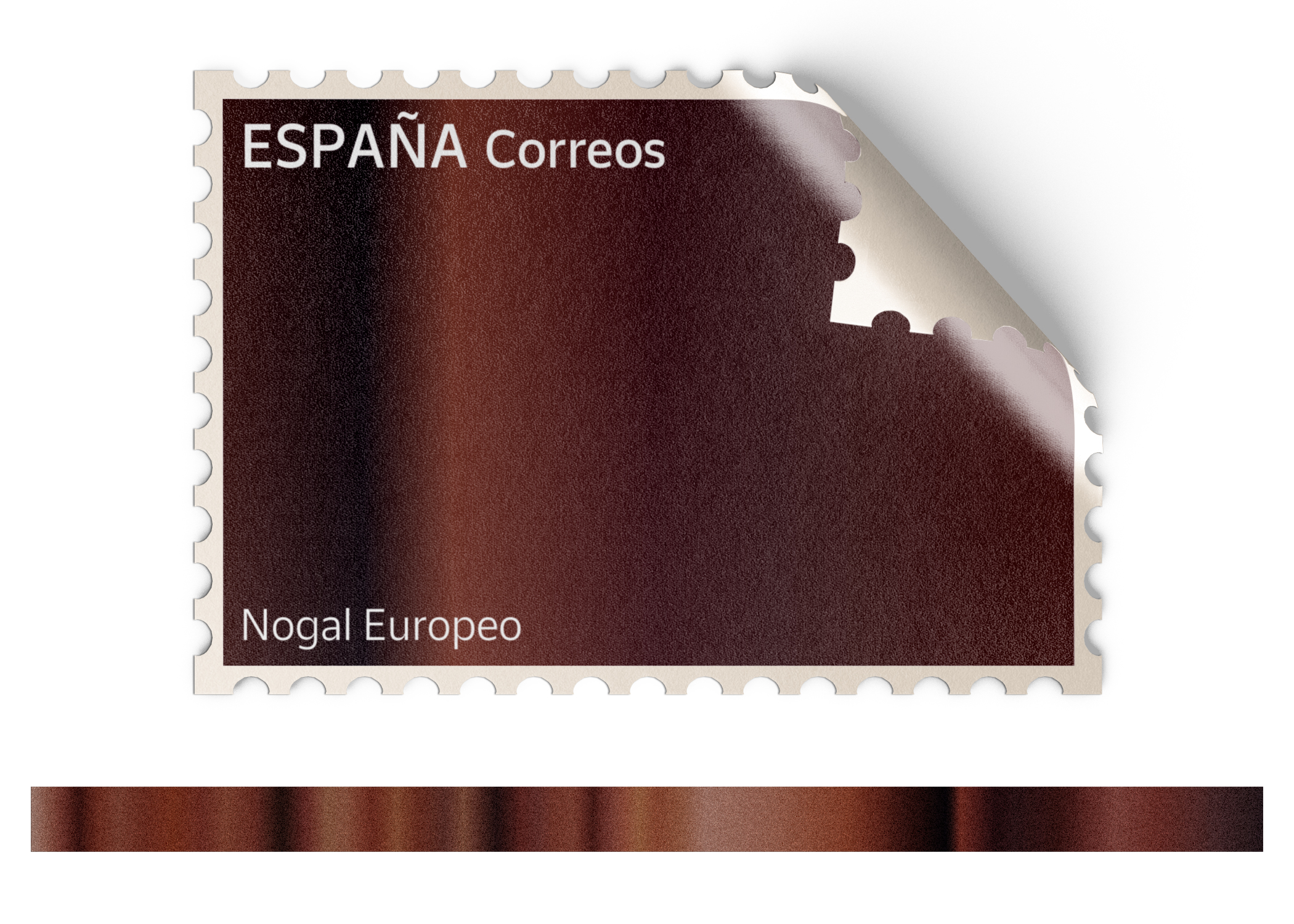

Inclán’s project centered on the heart of the tree, looking at the color profile of a cross section of the trunk. With colors derived from a zoomed-in view of a walnut tree core sample, he created postage stamps for postcards he made with old family photographs. Written on the back were messages to his grandfather, in a walnut ink Inclán developed, bringing the project full circle: “The tree sends memories in postcard form to my granddad in heaven.”

The Fly Book: The Essence of a Housefly

Frieja White, MFA Communications Design ’25

Professor: Matt Martin

Batting, buzz, breakdown, hovering, resting, transitory, vibration—these were some of the words Frieja White came up with in her exploration of the housefly, a being she chose to work with for both how we perceive it and how it perceives.

“What drew me to the housefly was its status as a creature often dismissed or overlooked,” White says. “Despite being seen as an annoyance, the housefly has complex behaviors and ecological roles worth examining. Its ability to thrive in human-altered environments, coupled with its unique communication through wingbeat frequency, piqued my curiosity.”

“This project connects sound, motion, and material.”

The wingbeat would become central to White’s final project. White created a video projection showing a mirror image of bound cardboard booklets with wooden panels at the center, shaken in the air in a wing-flap motion.

The batting—the concept White ultimately focused on in her explorations—creates a strong sound when the pages strike against the board. (The books were displayed along with the projection.) Sped up as the video progresses, the audio brings to mind the zipping sound of a housefly.

But White was also interested in the way the fly senses the world: “I was fascinated by its extraordinary vision, with compound eyes that provide nearly 360-degree panoramic views and process approximately 250 frames per second—far surpassing the human perception of 24 frames per second for a smooth movie experience. This vision allows flies to detect motion with incredible speed, offering a mosaic-like view of the world through thousands of tiny visual receptors called ommatidia.”

“Their intricate sensory world and misunderstood ecological contributions inspired me to explore how something so common could provoke deeper thought about our relationship with nature.”

Genesis: A Bacterial Taxonomy

Yasmeen Abdal, MFA Communications Design ’25

Professor: Maria Gracia Echeverria

It began with a butterfly—the brimstone, Gonepteryx rhamni, a small vibrant-green species whose leaf-shaped, vein-patterned wings bear a remarkable resemblance to the foliage it lives and eats among. For the brimstone, mimesis, or mimicry, is a means of protection and survival, of hiding—but as Yasmeen Abdal found, imitation might function another way as well, to help us see.

In her final project for the Cross-Disciplinary course last year, Abdal took inspiration from the brimstone to explore the idea of mimesis: “I examined the uncanny—the tension between the familiar and the unfamiliar. How does deception or imitation reshape our perception of the world? How can contamination mimic natural beauty, blurring the line between the artificial and the organic?”

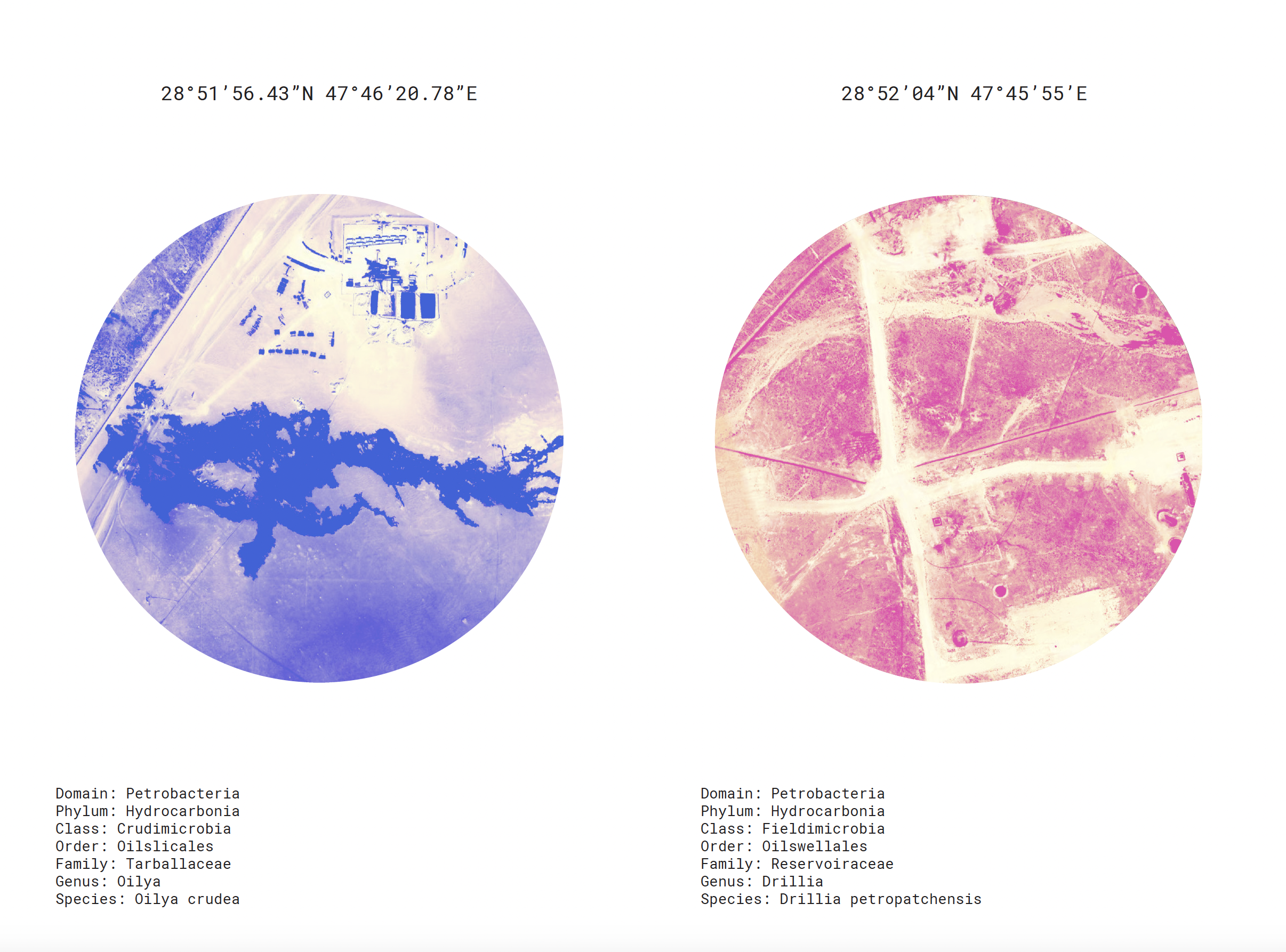

For the project, “Genesis: A Bacterial Taxonomy,” Abdal, who grew up in Kuwait, looked at contaminated sites in the country—“oil fields, camping grounds, and the world’s largest tire graveyard” from a vantage that zoomed out far from the familiar.

“Elements of beauty emerge from unexpected sources, blurring the lines between contamination and nature.”

From an aerial view, sprawling fields of tires resemble bacterial clusters in a petri dish, uniform dots heaped and radiating out on a flat, pale surface. “By analyzing these environments on both micro and macro scales,” she observes, “I revealed how their spatial presence deceives perception.”

She developed a hypothetical guide to new species of bacteria whose taxonomy derives from the reality of its composition—like Rubberus tireus and Drillia petropatchensis. Accompanying it is what Abdal calls a “National Geographic-style parody video” (above), another take on mimicry and deception.

“The project serves as an allegory,” she says. “It introduces a speculative bacterial family that embodies the modern ecological paradox—where beauty emerges from contamination, reshaping our understanding of nature’s transformations.”![]()

A Reading and Listening List for Noticing Differently

Explore just some of the readings and references from the MFA Communications Design Cross-Disciplinary Studio.

- Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer

- Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake

- The Mushroom at the End of the World by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing

- Staying with the Trouble by Donna J. Haraway

- A Psalm for the Wild Built (Monk and Robot series) by Becky Chambers

- Rambunctious Garden by Emma Marris

- Emergent Strategy by adrienne maree brown

- Late in the Day: Poems 2010–2014 by Ursula K. Le Guin

- A Forest Walk, a guided practice podcast from Emergence Magazine, with Kimberly Ruffin

Learn more about Graduate Communications Design at Pratt