When Yuliya Dzyuban, assistant professor in Pratt’s MS in Sustainable Environmental Systems program in the School of Architecture’s Graduate Center for Planning and the Environment (GCPE), moved to Phoenix, Arizona, to work on her PhD, she hadn’t yet realized how hot it gets there. Summers in the city can reach a high of 119°F. That extreme heat affected Dzyuban, who did not drive and quickly found public transportation unreliable. Walking in the Phoenix sun was, she says, shocking: “It was like an oven. Being out was a matter of survival.”

Despite having what she describes as a low tolerance for heat, Dzyuban saw an opportunity. She went out into Phoenix to better understand how urban design can influence thermal comfort

in a hot desert climate. First, she looked into the safety of public transit riders, surveying their experiences of heat. Then, she got involved with her university’s partnership with the City of Phoenix and hosted her first “heat walk.” For this, Dzyuban took participants on a walk in a neighborhood slated for redevelopment. She measured environmental variables and recorded how changes in the urban landscape affected the thermal comfort of walkers. Dzyuban visualized this data in a map, showing how design and subtle changes in microclimate can influence participants’ heat sensations, informing the future neighborhood redevelopment plans.

These projects were so successful that Dzyuban went on to expand her ambitions and take her walks and research into public transportation to some of the other hottest cities in the world, such as Singapore and Hermosillo, Mexico. It wasn’t until taking her walks to Singapore that Dzyuban began to realize their full potential. While participants joining the walks shared their immediate thermal sensations, she also realized that these walks could be a powerful tool for community building and raising awareness around climate change. “It’s experiential,” says Dzyuban. “People have fun when they do it, they start asking questions, and it becomes a multisensorial and an educational experience.”

Last year, Dzyuban brought her research to Pratt’s GCPE. She has incorporated environmental data collection into her Microclimate Assessment for Urban Design course and guided walks as part of Pratt Earth Action Week and Climate Week NYC. In the fall, Dzyuban was appointed to the New York City Panel on Climate Change (NPCC), where she is working alongside academics and practitioners from institutions across New York City to assess new research that would inform climate change–related policies in the city.

Dzyuban spoke with Prattfolio about mapping and recording lived experiences of heat, working with city dwellers around the world, and how imagining yourself as a squirrel or a butterfly might be a useful first step toward creating a more habitable city.

Let’s talk about your heat walks. Why is community involvement in your walks important?

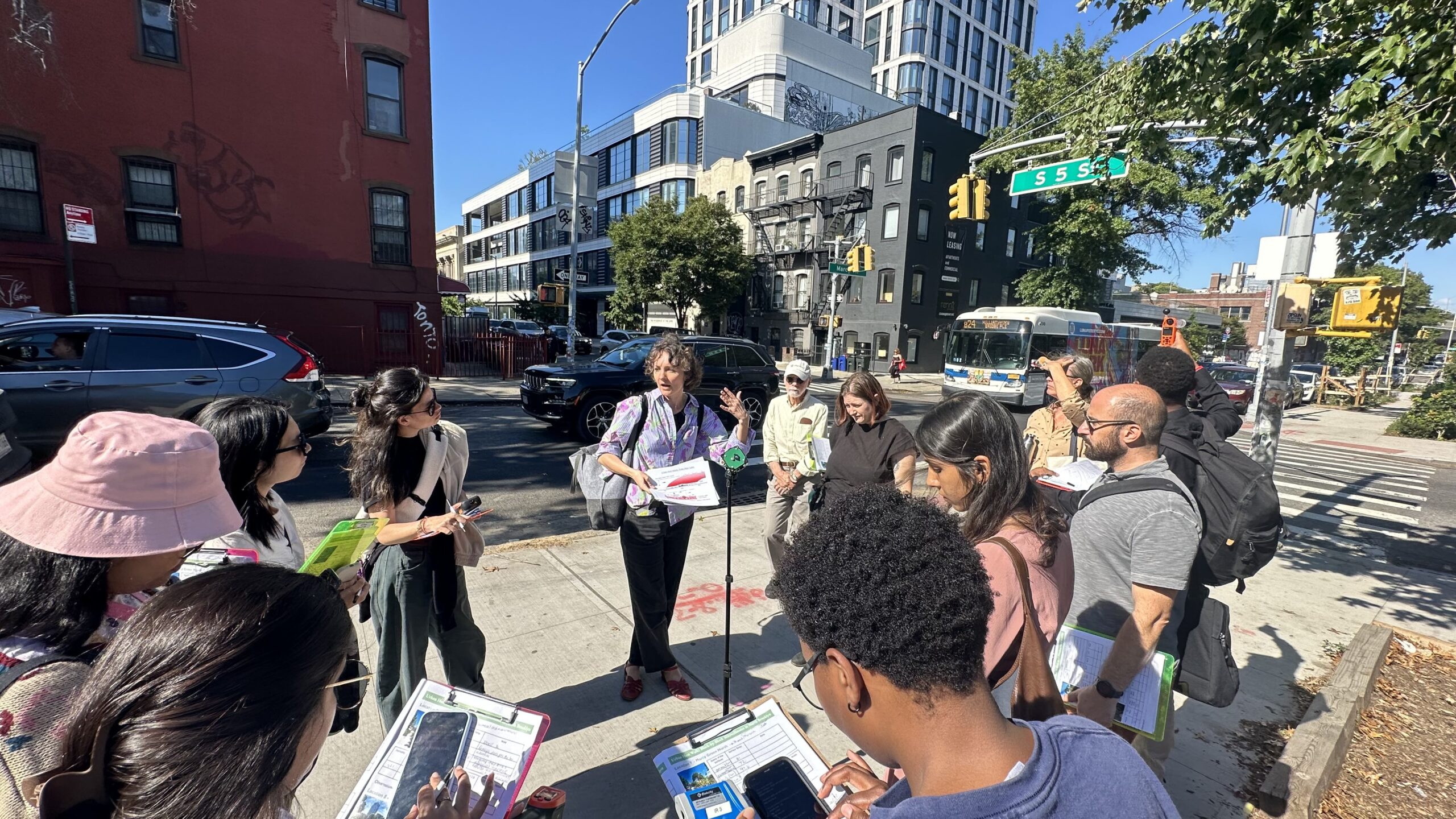

My walks are a way to raise awareness and incentivize change. For example, I organized a walk in partnership with the environmental justice organization El Puente, and [nonprofit park conservancy] North Brooklyn Parks Alliance for Climate Week NYC, guiding participants through a complicated neighborhood history shaped by discriminatory policies that influenced current microclimate and air quality conditions.

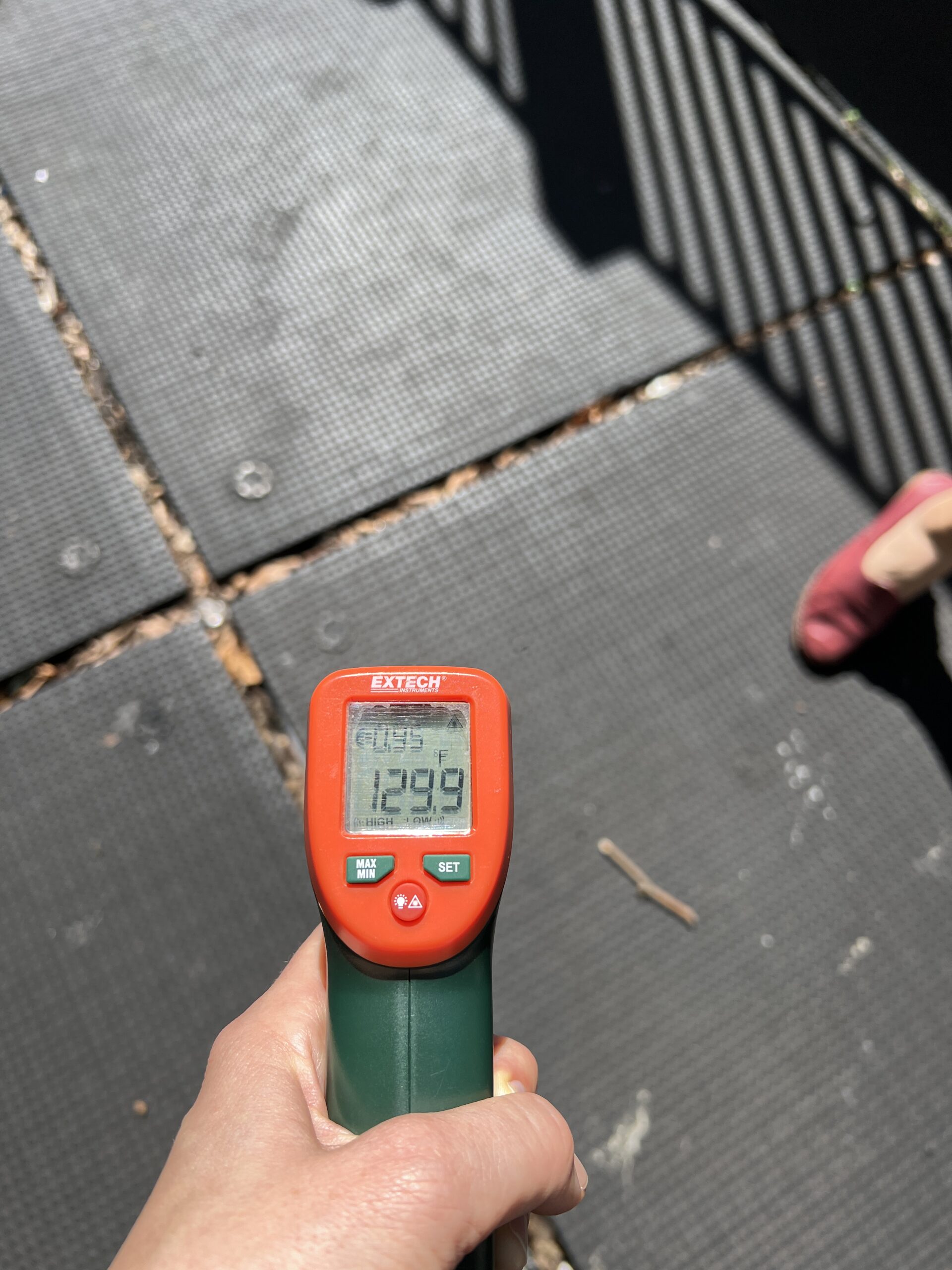

Measuring and recording the difference in environmental variables across several neighborhood spaces (e.g., a playground, a day laborers pick-up site, a highway overpass), we discussed how variations in built form, materials, and vegetation shape urban climate and influence thermoregulation of pedestrians. My devices allow me to measure a range of microclimate variables, rather than just air temperature—a common metric we all know—because it doesn’t tell the whole story of our heat experience. For example, radiation that our bodies absorb from the sun and nearby surfaces is one of the most influential factors in our thermal comfort during summer. There is a big difference in how hot we feel in the shade versus the sun. By measuring mean radiant temperature, we can actually see those differences.

After the walk, I showed how the measurements we took can be mapped to create visual representations of neighborhood conditions, emphasizing local hot and cool spots. I hope that such maps can be used as visual evidence by environmental justice and nonprofit organizations to advocate for more high-quality green space where it is most needed.

You also do walks with your students and with professional organizations. How do your walks teach participants from so many different backgrounds about the effects of heat?

As a part of my class at Pratt, I train students in developing and testing methods to track and map individual heat exposure. They learn to use state-of-the-art biometeorological instruments and collect and visualize data. Based on their findings, students propose site-specific urban design recommendations to improve thermal conditions in NYC neighborhoods. This is one way to raise awareness and transfer skills to emerging sustainability practitioners.

Last year I organized a thermal walk with the AIA [American Institute of Architects] New York Civic Leadership Program, exploring how design could increase biodiversity in the city. By incorporating role cards that represent human and non-human species, I encourage participants to think from different perspectives. For example, an older person with high blood pressure, or a teenager with asthma will experience heat in different ways due to health conditions influencing thermoregulation. The role can also be a butterfly whose wings will burn if it’s in the sun for more than 10 seconds, or a squirrel that splays on the ground to thermoregulate. By measuring microclimates and surface temperatures of surrounding materials (for instance, sun-exposed asphalt can reach 130°F), participants are encouraged to think how to design cities inclusively for residents with different abilities and health conditions, as well as for other species too.

Through such experiences, participants better understand existing environmental inequities. They can take informed action via professional practice, advocacy, or volunteer initiatives toward heat-resilient design of cities.

How have you brought your research to NPCC?

My prior experience on studying the interactions between extreme heat, urban form, and thermal comfort enabled my participation as a member of the NPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report.

The aim of the report is to assess the state of the science regarding the risks and impacts of climate change hazards in New York City. As part of the process, we engage with city agencies and coalitions of professional and community organizations to define the priority areas of the report focus. I am contributing to the chapter that is assessing the interactions between heat, humidity, and air quality and their impacts on outdoor and indoor conditions of public and private spaces, such as playgrounds, schools, and residences.

Heat is a growing health risk for New Yorkers; on average, about 350 New Yorkers die from heat-related illnesses every year. Furthermore, exposure to heat can aggravate chronic illnesses and impact productivity and comfort. This work will provide scientific grounding to developing adaptation and mitigation solutions that would help to protect the most vulnerable New Yorkers.

On Heat Walking in Three of the World’s Hottest Cities

Phoenix

Growing up [in Ukraine], in a city that prioritizes walking and public transit, I struggled when I moved to the Phoenix Metro Area. Walking and waiting for a bus could become a life hazard in the extreme Phoenix heat. That motivated me to research thermal conditions of public transit users. I measured microclimates, surveyed riders, and identified infrastructure that could make them feel cooler. I found that conditions are quite extreme and can be dangerous, causing heat stress, and temperatures of surface material exposed to the sun can cause skin burns. The City of Phoenix is taking active steps to protect heat-vulnerable populations, balancing conflicting priorities of tree planting, water scarcity, and urban growth.

Hermosillo, Mexico

Unlike Phoenix, the majority of people in Hermosillo take public transit. It’s a very different situation. At the time of my research, some buses did not have air conditioning. We installed sensors in those buses, and we found that, in some cases, the temperature could go up to 50°C [122°F]. Furthermore, I found that bus-stop shelters installed by third-party contractors in exchange for advertising space offered minimal shade protection. As a result, bus-riders preferred informal stops under the tree shade. This example shows the importance of prioritizing thermal safety when designing both grey and green urban infrastructure for the city in extreme climate.

Singapore

Singapore, on the other hand, is a dense tropical city with lush vegetation. The public transit system in Singapore is well-developed and efficient, and the majority of the population relies on it. I found it easy for me to adjust there. High vegetation coverage is a result of the government initiative to prioritize city in nature that supports this vision by expansion of nature trails, parks, and increased connectivity between the green spaces. As part of the Cooling Singapore project that I was a part of, I helped to advance this vision by evaluating the effect of urban nature on residents’ perceptions and health through measuring and modeling the impact of the built environment and trees on urban climate and thermal comfort sensations.

Learn more about Sustainable Environmental Systems at Pratt