The miter joints were eluding Cadyn Chien and Cristian Maldonado, both MArch ’25. It was trial and error at scale as they built their project for their Advanced Design Research studio, a private chapel with unique geometry that required joint cuts at more specific angles than the standard 45 degrees. Adding layers of complexity to the project, the pair was working with unique constraints, as the model would need to break down flat for an international trip.

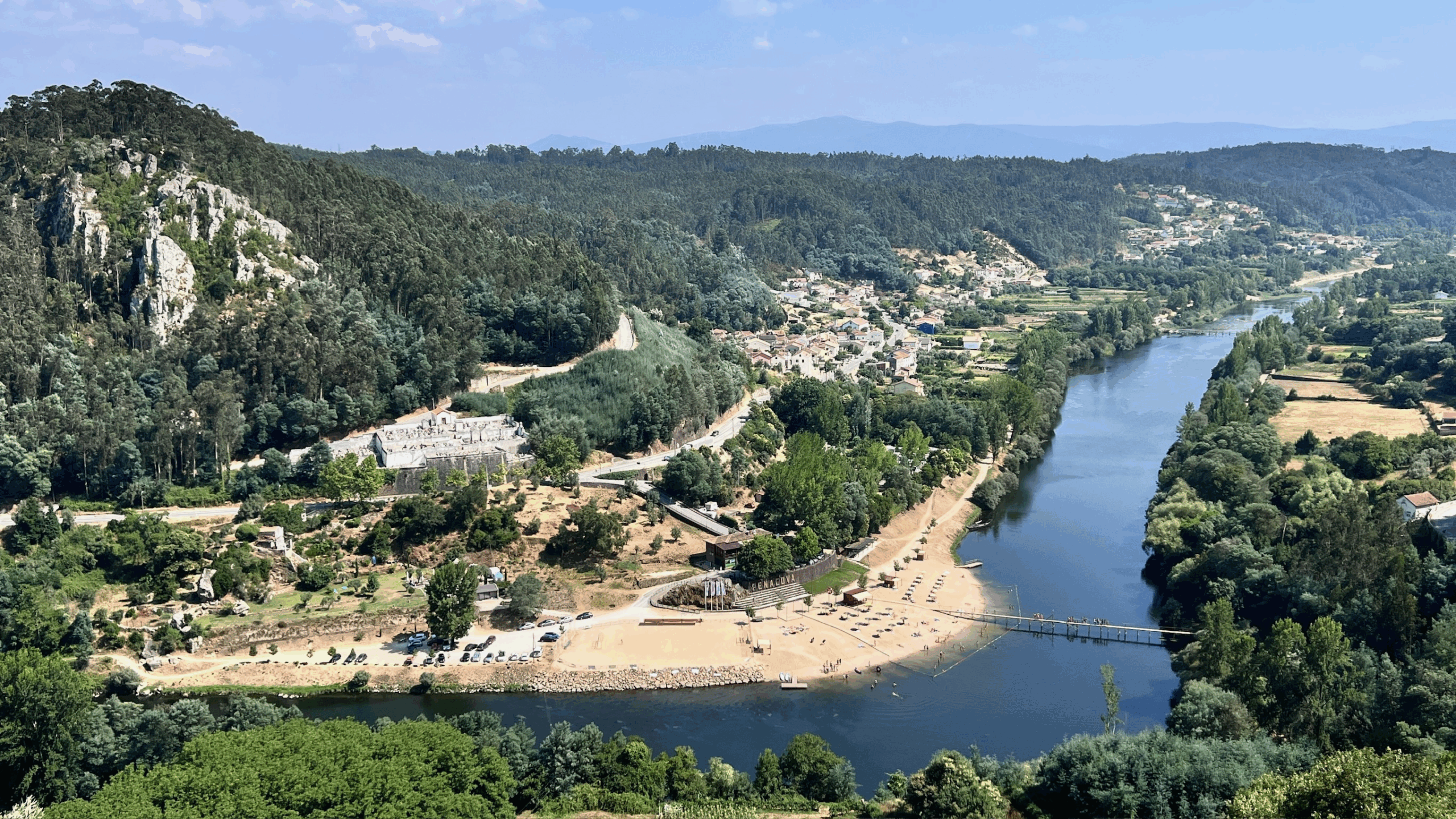

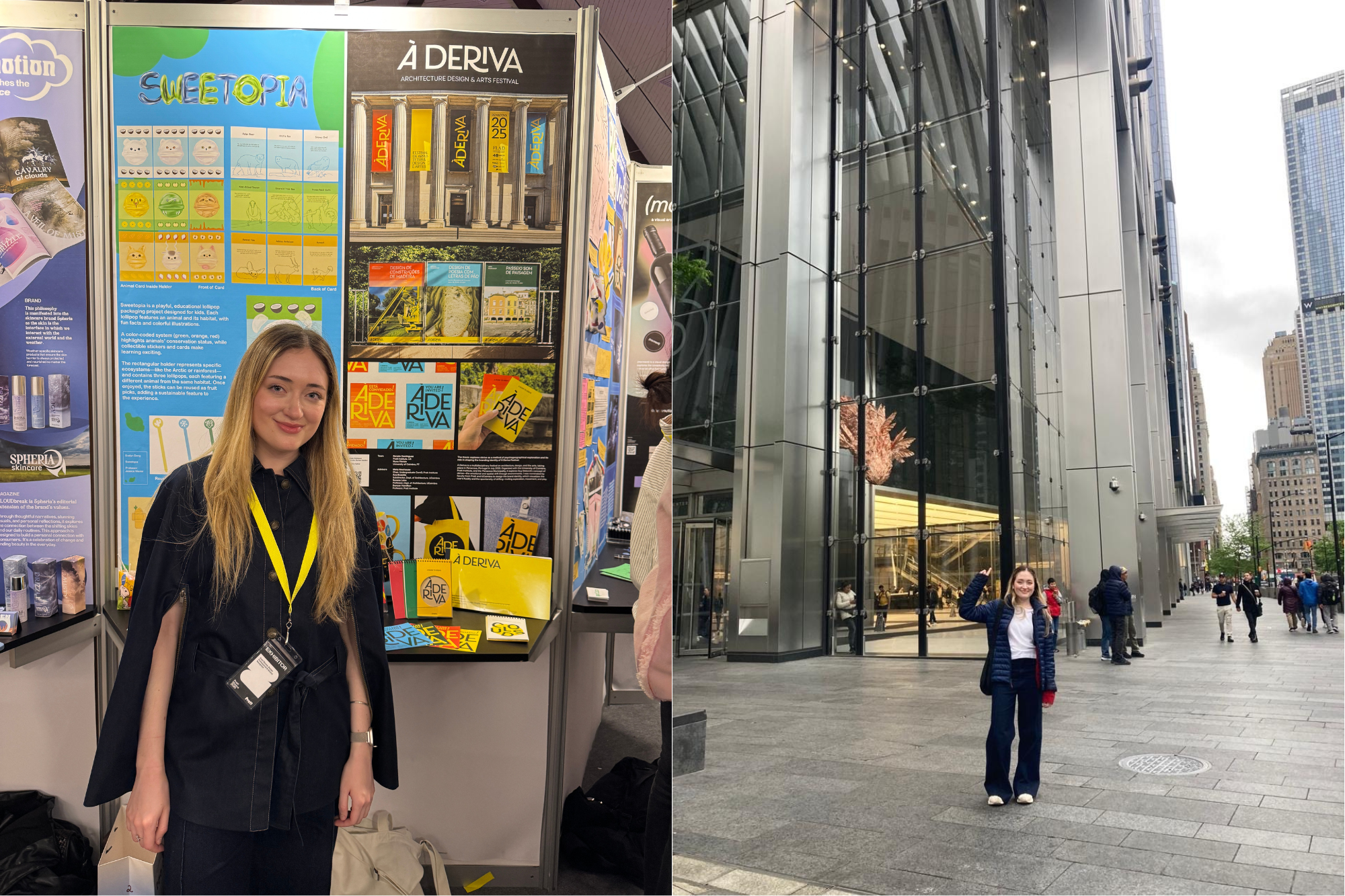

The finished piece would be part of a group of installations and art and design activations Pratt Institute faculty and students were preparing for this summer’s À Deriva Architecture, Design, and Arts Festival in Penacova, Portugal, an event Pratt and the University of Coimbra developed in collaboration with the community of Penacova through seed funding from the Foundation for Luso-American Development in Lisbon. The festival presented students and faculty from across disciplines at Pratt with opportunities for codesigning with a community, learning about regional culture, and exploring new practices and materials.

Assembly Required

From the start, Chien and Maldonado knew they would be working with plywood, since the structure had to be taken apart and reassembled in Portugal. Although the material was flat-packable and ideal for prefabrication, it was prone to cracking and required a lot of troubleshooting.

“We were dealing with really thin wood,” Chien said. “Plywood can chip off and break if you sand too hard. We had to cut a bunch and think about the material limits and possibilities while making it.”

The intricacies of making unfolded in Pratt’s School of Architecture woodshop.

“We went to the woodshop and that, for me, was the first time that I had to work with every machine,” Chien said. “Cutting, sanding boards down, trimming them, using the table saw. We did a lot of wood joinery exploration, thinking about how the different pieces of wood can interlock with each other and how they also speak of the narrative, so that some joints are more structural and others are more expressive.”

This expressiveness would help “Chapel of Play” achieve a balance of playful and sacred elements as part of the Design 6: Storied Cabinets studio taught by Graduate Architecture, Urban Design, and Landscape Architecture faculty Joe Vidich and Olivia Vien, which asked students to design and build structures, inspired by Penacovan culture and history, that “blur boundaries between the container and the contained, the functional and the fantastical.”

Over the course of the semester, bringing the structure from 2D to a scale model to an accessible piece of furniture presented many challenges, none more so than getting the miter joints right. Figuring out the exact angle required a level of precision and experimentation that exceeded what digital tools like Rhino or laser cutting could offer. Small mistakes during the cutting process could lead to chipping or poor alignment, so they learned to pay close attention to the grain, flexibility, and fragility of the material itself.

-

![Close-up of blue ropes or cords looped through metallic rings and anchored to a wooden frame. The ropes are tied in knots at the bottom, showcasing a structured, linear pattern. The background consists of a light wood surface, emphasizing the contrast between the blue cords and the natural wood tones.]()

-

![An interior space predominantly painted in bright orange. The view is from a low angle, looking up toward a skylight at the top, which allows natural light to seep in. There are two small square openings in the orange walls and strands of material hanging down, adding texture and dimension to the space.]() Photos by Rachel Guo, MArch ’25

Photos by Rachel Guo, MArch ’25

“There was a lot of back and forth communication between us and the [woodshop] workers,” Chien said, referring to the technicians who supervised the machines, and explaining how even a basic misunderstanding about whether they were referring to the cut-off angle or the remaining angle could derail a cut.

There were other elements to consider in this build as well—things like screw type and seal for the paint finish, which had to factor in climate, durability, and ease of reconstruction. “We had to think about safety, shipping, and how the wood would respond over time, especially since it’s a structure that allows people to enter,” Chien said.

The pair’s final composition was in itself a gateway to exploration and a new perspective. For the design, they arrived at a tall vertical structure placed on a horizontal base that invited visitors to enter through a low opening, an action that Chien and Maldonado began to see as a “mini ritual.” “It’s telling the body, ‘you have to change your position and crawl inside.’ You have to slow down and think, ‘is this opening big enough for me to crawl in?’” Chien said. “Then there’s this shift that happens when you’re inside, not just formally, but geometrically as well. The inside space is painted in this vibrant warm orange that’s meant to be stimulating and intimate, inviting both curiosity and a sense of pause as the body feels like it’s wrapped in filtered sunlight.”

New Tech Meets Traditional Materials

In Portuguese, the word deriva refers to a state of figuring things out as you move through them, maintaining a sense of playful curiosity amid both the familiar and the new. This concept animated the year-long collaboration between Pratt and the University of Coimbra, during which teams researched, designed, and built the projects that would be installed and displayed in Penacova, finding inspiration in local culture and materials and conversations with community members.

On a fact-finding and story-collecting trip, Pratt faculty held a community town hall in Penacova and toured local architectural sites, museums, and manufacturing spaces, where they were able to hold and feel cork. This experience laid the groundwork for two undergraduate studios tasked with developing installations for the festival. (Read more about the student experience at the center of À Deriva.)

Portugal is the largest producer and exporter of cork in the world, and the manufacturer Corticeira Amorim agreed to donate cork for use in the festival projects. Even then, the material’s fragility was apparent to Richard Sarrach, executive director of Production Systems and adjunct associate professor of undergraduate architecture. When he brought the ultra-thin 2mm sheets of cork to Assembly Loop Lab (ALL), the design-fabrication facility under Production Systems in the Technology Division, they cracked and tore easily, resisted traditional fabrication methods, and appeared limited in their ability to occupy space.

Through continued experimentation, Sarrach and Scott Sorenson, associate director of Production Systems and visiting assistant professor of undergraduate architecture, discovered that specialized equipment could transform how cork performed and appeared.

Using a UV printer, typically employed for printing on rigid surfaces like glass, metal, and plastic, they applied ink directly to cork. Because the UV curing process hardens ink with light instead of heat, it allowed for varied surface treatments without damaging the material. The result was visually striking, lending the cork unexpected qualities. It shifted in appearance with the light, at times looking like leather, at others like metal.

Pairing this with the precision of the Zünd digital cutter, which sliced cleanly through cork “like butter,” the team was able to move beyond the flatness of the material. By stacking, folding, and rolling it onto itself, they created layered surfaces, going from paper-thin sheets to forms several inches thick. What began as a fragile, easily damaged surface evolved into a sculptural, dynamic skin.

For the festival, Sarrach and Sorenson incorporated the transformed cork into a cabinet of curiosities based on Portugal’s gastronomic brotherhoods—around 100 organizations dedicated to preserving culinary practices and traditions in Portugal. They selected nine related to Penacova to represent in their design. The figures were produced at ALL using Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) 3D printing with custom code that gave the brotherhoods a distinctive fuzziness, adding an ethereal quality to their forms.

“As visitors move around the installation, they experience shifting perspectives of these ‘conspiring brothers,’” Sarrach and Sorenson noted. “The cabinet serves as both shrine and stage, elevating these cultural guardians while inviting viewers to discover the rich tapestry of Portuguese culinary traditions they represent.”

Recipe for Connection

During one of the early visits to Penacova, Analia Segal, adjunct professor – CCE of fine arts, was intrigued by the concept of community ovens she kept seeing in small towns along the Mondego River.

“These are local brick ovens that people share for cooking and making bread,” she said, noting that they’re common throughout Europe. “The traditional Portuguese ‘biscoito’ endured long voyages, nourishing sailors and explorers as they set forth on their intrepid journeys across the seas.”

As she spoke with locals, she learned of bread’s importance as both a source of nourishment and a basis for community and wanted to explore the sculptural potential of breadmaking. During a 10-day return trip in March, she apprenticed with João Fernando Costa, a fifth-generation baker who she met at the initial town hall meeting, at his bakery Padaria do Largo.

-

![The inside of a traditional brick oven with a curved entrance. Inside, several dough rounds are resting on a stone floor, while a pile of smoldering embers and ash is positioned at the bottom, indicating that the oven is heated. The walls of the oven are made of beige bricks, creating a warm, rustic atmosphere.]() Segal was inspired by the community ovens located along the Mondego River and local baking traditions. Photo by Joseph Vidich

Segal was inspired by the community ovens located along the Mondego River and local baking traditions. Photo by Joseph Vidich -

![A variety of twisted and coiled pieces of baked bread, in different shades of brown and tan.]() Photo courtesy of Analia Segal

Photo courtesy of Analia Segal

“I learned the ropes of being at a bakery,” she said. “I went there early in the morning and learned different breadmaking techniques. I got to know the family and develop trust, which is a big part of the process. I felt like the impetus for this was learning and finding new models for transmission of knowledge in different settings. We came up with a recipe that was suited for a sculptural piece as part of a multimedia installation.”

Segal’s interest in this ancient practice inspired a workshop “that centered on the belief that we are not estranhos—not strangers—but companheiros: from cum panis—those with whom we share bread, gestures, and stories.”

“I felt that it was tapping into the instinct that everyone has to create,” Segal said. “Dough is very similar to clay, there’s no need for technical learning or explanation. It becomes more about giving room for dialogue.”

Pratt students and faculty, along with local citizens, joined her for the “mãos na massa” workshop at the start of the festival that sought to “remind us that making and sharing are ancient acts of connection, and that every loaf broken is an offering of presence.” Gathered around a table on the cobblestone street, the participants were asked to choose a word in their mother tongue that made them feel closer. They then kneaded dough and sculpted words like memory, community, and rio, the Portuguese word for river.

-

![A projection on a white wall displays the phrase "sou minha própria paisagem" in a stylized, golden font made of bread. The background consists of earthy tones and textures. To the right is a glass door revealing an outdoor area with trees.]()

-

![A wooden table outdoors displays various shaped pieces of dough arranged to form letters and words. Several hands are interacting with the dough, with one person's hand placing a piece. In the background, there are people standing. The ground surface is made of cobblestones.]() Photos courtesy of Analia Segal

Photos courtesy of Analia Segal

“As a contemporary artist, I choose the material that best communicates my ideas, so it’s not necessarily the bread that was important, it was the participatory experience, the collaboration with the community, the traveling, the language and translation,” said Segal, who is also currently a PhD candidate at Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. “There’s a lot about this project that continues my research inside and outside of the classroom. It has planted new seeds to develop.” ![]()