“Cheryl D. Miller, president of Cheryl D. Miller Design, had no idea that her 1987 Print magazine article, ‘Black Designers: Missing in Action,’ would catapult her to national prominence and be a catalyst for efforts to raise consciousness. In fact, she still receives calls and letters referencing that first documented account of the dilemma of Black designers.” These words, penned by Brenda Mitchell-Powell in a 1991 AIGA report—describing the organization’s efforts to address staggering inequity in the graphic design field—are as true and relevant today as they were three decades ago.

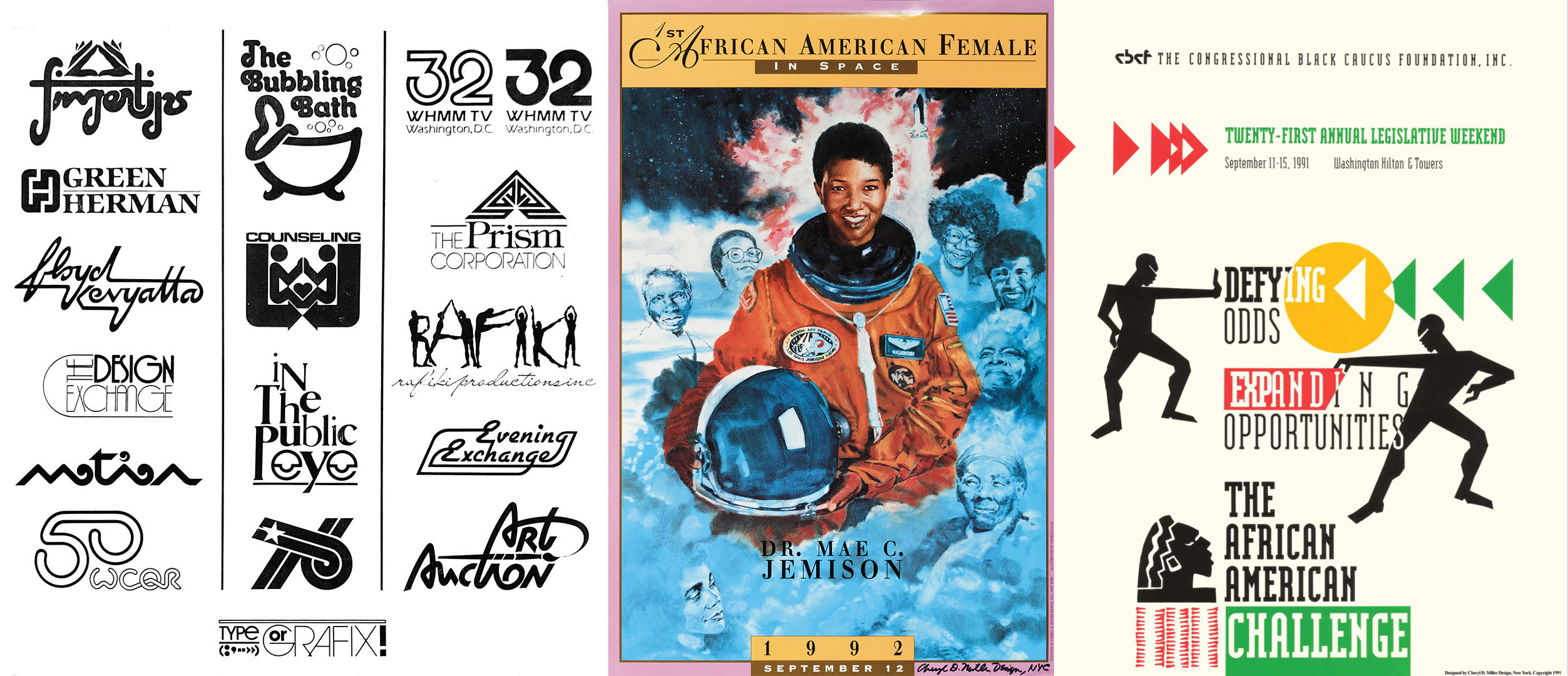

Thirty-five years ago this fall, Miller’s landmark story arrived in the pages of Print magazine, raising the question of “why the design field hasn’t made better use of the talents of Blacks who have already contributed so much to graphic communication.” The piece was a critique and a call to action, illustrated with a dynamic selection of work being made by Black designers like Michelle Spellman, Eli Kince, Carol Porter, Kirk Brown, and more.

The story of that article began with Miller’s Pratt thesis. Two years out from her master’s and busy at the helm of one of the first Black woman–owned design firms—Cheryl D. Miller Design, Inc., NYC, on Lexington Avenue—she felt her thesis beckon from her office shelves. “It sat in my mind. I thought, this cannot stay here,” Miller recalls. “I took a copy of it, and I marched it over to Print magazine,” one of the industry’s definitive journals. By the time Miller returned to her office, her phone was ringing—it was editor in chief Martin Fox offering her an editor and a fee to write an article based on the thesis; she agreed.

This was the continuation of a charge Miller had seized upon at Pratt, when Etan Manasse, then chair of graduate communications design, told her that adding to her already robust portfolio would not earn Miller her degree. Instead, as a requirement for Miller’s thesis, Manasse gave her this assignment: “I want you to make a contribution to the industry.” She would have to write her way to the master’s.

“I knew what he meant, and I knew what I would do—and I knew that I had to do it,” Miller says. “The Black designer wasn’t on the page, and I needed to find out why.”

Before establishing her business in New York and attending Pratt, Miller had built a thriving broadcast design career in Washington, DC. The move to New York propelled her to expand her expertise to publication design and corporate design, and to develop her design-business vision at Pratt. In both cities and throughout the Mid-Atlantic, Miller had witnessed the same hardships. “My community of Black creatives at the time, we were coming out of Jim Crow, trying to get into business,” she says. “I used to have portfolio reviews every week, helping people get jobs and get out of this snag. It was systemic. In the design business, you have to have friends, you have to have a network to get into a studio. I knew the only way to get in the game was to make the game. So with that, my office was Grand Central Station. I saw the disenfranchisement, I saw the erasure. I knew the problem, and I needed to document it.”

Miller’s thesis, “Transcending the Problems of the Black Graphic Designer to Success in the Marketplace,” chronicled with penetrating clarity the pressures and challenges Black designers faced in their careers, from lack of familial support as they pursued their educations, to the high cost of tuition and materials, to an absence of mentorship in the field. The thesis and the article that followed laid the groundwork for the industry to confront issues that, while they persist today, have ever more historical documentation, scholarship, and energetic advocacy generating momentum to address them, due to Miller’s work and that of those who continue to build upon it.

In recognition of her advocacy and visionary contributions to the field as a designer, writer, educator, and legacy creator, Miller has won numerous awards, most recently, the AIGA Medal for Expanding Access, the Cooper Hewitt National Design Award, and the distinction of being the inaugural Honorary IBM Design Scholar—all in 2021—among other honors. In October, Miller was inducted into the One Club for Creativity’s Creative Hall of Fame.

Meanwhile, the work continues. As an educator today, Miller urges her students, who range from young designers to seasoned design educators, to lean into their own advocacy, and to amplify Black voices—their own voices—in design history. Her words of advice to emerging designers: “Create your aesthetic and your voice and write it into the canon. In my primary class, Decolonizing Graphic Design, from a Black Perspective, I decolonize the basic 15-week history of graphic design, from my cultural lens. I’m going to teach you the canon because you need to know it. But you also need to know that there’s more to the story, and you have the story in you.”