At Pratt, a particular ethos of concern for social justice, the quality of civic life, and community care is palpable, woven through student projects, faculty research, the work undertaken by the Pratt Center for Community Development, and connecting back to some of the Institute’s founding values. Every new contribution to the long effort for change adds to a continuum, though some milestones haven’t made it into the institutional retrospectives, timelines, or archives, pointing to the need for more inclusive histories. An interdisciplinary initiative called Preserving Activism intends to address those absences, shedding light on the deeper story of that throughline, making the history of advocacy and action at Pratt publicly accessible.

Preserving Activism began in 2019 as a proposal funded by the Strategic Plan Oversight Committee, or SPOC, grant awarded to Academic Director of the Historic Preservation master’s program and Adjunct Associate Professor in the Graduate Center for Planning and the Environment Vicki Weiner, with collaborators Professor of Art and Design Education Heather Lewis; Visiting Assistant Professor of Art and Design Education and Historic Preservation Rebecca Krucoff; and Associate Professor of Interior Design Keena Suh. Their intention was to “tap into the pedagogies and values-driven research methods of the Historic Preservation, Art and Design Education, and Interior Design graduate programs” in which they teach, says Weiner. The team soon expanded to include Pratt’s Virginia Thoren and Institute Archivist and Visiting Assistant Professor Cristina Fontánez Rodríguez and User Experience Librarian and Visiting Assistant Professor Nicholas Dease. Currently, long past the initial funding period, Preserving Activism continues to evolve as a hub for collaborative, interdisciplinary researchers—students and faculty—who are focused on the history of activism both within Pratt and extending out to the surrounding community.

One early project initiative is an ongoing, multidisciplinary graduate course, Preserving Activism Beyond and Between Pratt’s Gates. Initially offered in the spring of 2020 by the Historic Preservation and Art and Design Education programs and taught by Lewis and Krucoff, the course, like many others, was disrupted by the pandemic. Instead of engaging the public through a physical, public event, as originally intended, students shifted their public history exhibition to the web, exhibiting their research and findings in a digital presentation that launched the first iteration of the Preserving Activism website. Separately, Preserving Activism graduate assistants and Pratt Archives graduate assistants collaborated to organize another digital showcase, Protest at Pratt: Student Activism Then & Now, made available through the Pratt Institute Archives and Special Collections’ Online Exhibits portal.

“Students were activating records and at the same time creating new historical records for the archives.”

Cristina Fontánez Rodríguez, Virginia Thoren and Institute Archivist and Visiting Assistant Professor

Even through the challenges of the past three years, Preserving Activism took off. The team received an Impact Award at the 2021 Research Open House and a Taconic Fellowship grant in 2022, which has helped expand their research. According to Lewis, “It grew into something larger, with much more close collaboration, cross-discipline, cross-school. And the results are a website, exhibitions, continuing research, historical research, oral history research, and more direct collaboration between the library and Preserving Activism.”

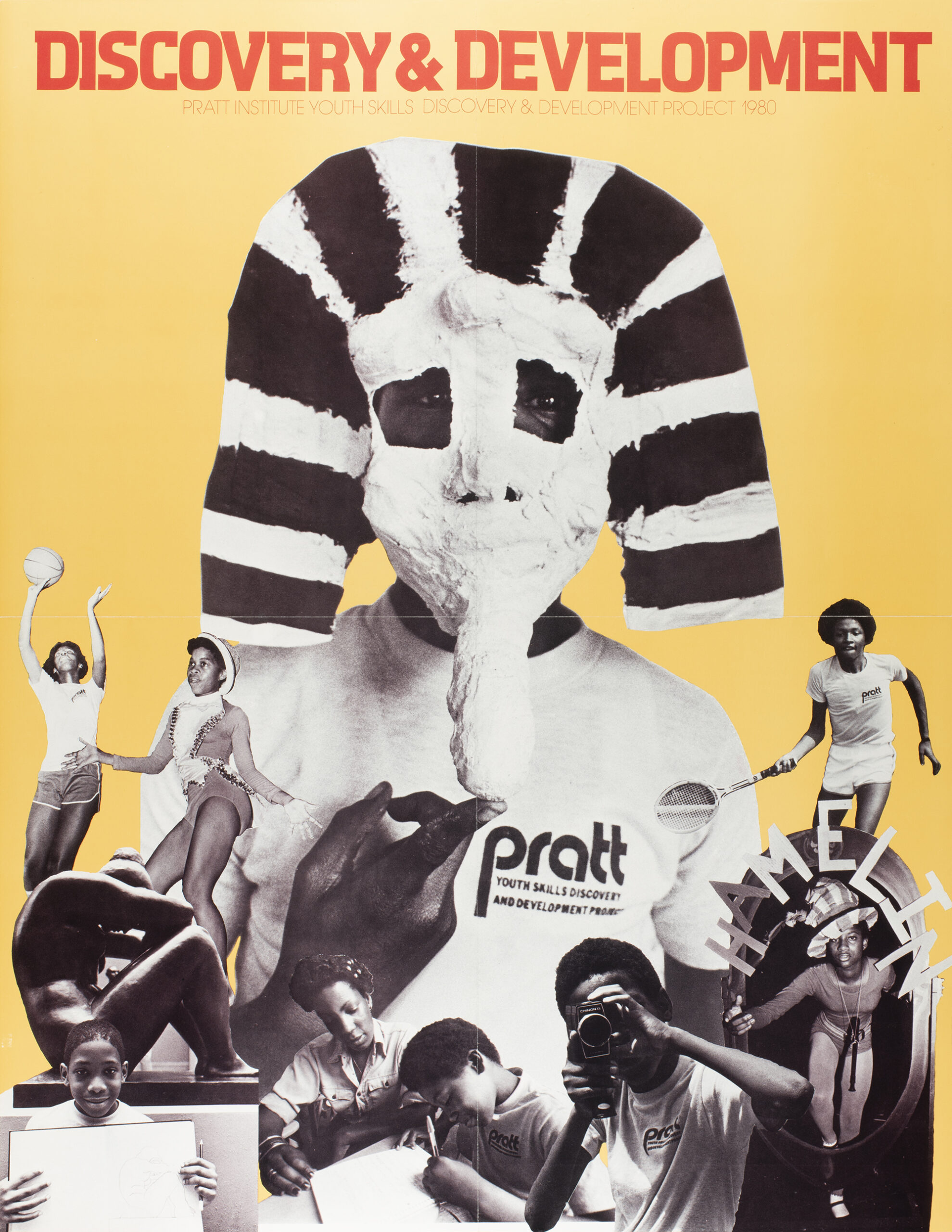

Last spring, as COVID restrictions subsided, Preserving Activism collaborators showcased their work in a public space—in an exhibition on Myrtle Avenue, which has been closely connected to the Pratt community through the Myrtle Avenue Brooklyn Partnership (MABP). Titled A Hidden History of Pratt’s Summer Youth Programs, the exhibition was based on student research from the Beyond and Between Pratt’s Gates course and included images from a set of photographic contact sheets by Pratt alumnus Marc Weinstein, BFA Photography ’74, that were preserved in Pratt’s archives.

These photographs by Weinstein—images of young people painting, sculpting, working with video cameras, and showing their creations on Pratt’s campus and at cultural locations around the city—shed light on a nearly forgotten program for local school children in Central Brooklyn in the early 1970s. The images prompted the students and faculty of Preserving Activism to delve into the lesser-told history of Pratt’s summer youth programs, founded by Horace Williams, BFA Fashion Design ’70, a longtime staff member at Pratt who was the Institute’s first Black vice president. In 1973, it was Williams who joined with fellow activists in the Black Student Union to demand a more diverse faculty and student body, a revamped curriculum, and summer programs open to young people in Central Brooklyn.

According to Fontánez Rodríguez, “Students were activating records and at the same time creating new historical records for the archives . . .. It was a perfect jumping-off point for collaborating and thinking of the archives as something very inclusive.”

The exhibition A Hidden History of Pratt’s Summer Youth Programs presented the photographs in installations in seven storefronts along Myrtle Avenue, in collaboration with Myrtle Avenue Brooklyn Partnership, and paved the way for the project to imagine future public presentations. A recent collaboration has been with Foundation Expanded: Myrtle Avenue Public Projects (a Pratt program, also initially supported by Pratt strategic funding, that connects student and faculty work with the public at Myrtle Avenue Plaza, in collaboration with MABP). A public exhibition, Elevated Voices: Elders Speak of Transportation Access, is installed in the windows of Khim’s Market at Myrtle Avenue Plaza, presenting Suh and Lewis’s recent collaboration with Alan Minor and Luke Ohlson of 7Cinema. The project presents an accumulated history of discriminatory policies and practices in transportation access, examined through oral histories of elder community members who live in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Clinton Hill, and Fort Greene.

Meanwhile, the collaborators’ work continues to be accessible digitally, with a new website, preservingactivism.org, recently launched.

“I’m excited about the potential to start teaching digital accessibility and generating more awareness of how to create content for the web that is inclusive,” says Dease. “The new website, preservingactivism.org, will give more flexibility, not just pictures and text: interactive experiences, timelines, pushing boundaries, and experimenting with archives and images.”

Suh adds, “As we discover projects and research, we’re hoping that we can offer a public, shared platform for these. That is something we would like to build upon, to try to consolidate all this [work], so that it becomes an accessible repository and resource.”

Looking to the future, Weiner sees ongoing momentum for the research and storytelling that will grow in that space. “We’re very excited to bring students, faculty, activists, and other collaborators together to join us in uncovering and highlighting the many layers of history of activism at Pratt and in the Pratt communities.”

Preserving Activism at a Glance

A look at some of the research areas Preserving Activism projects are exploring.

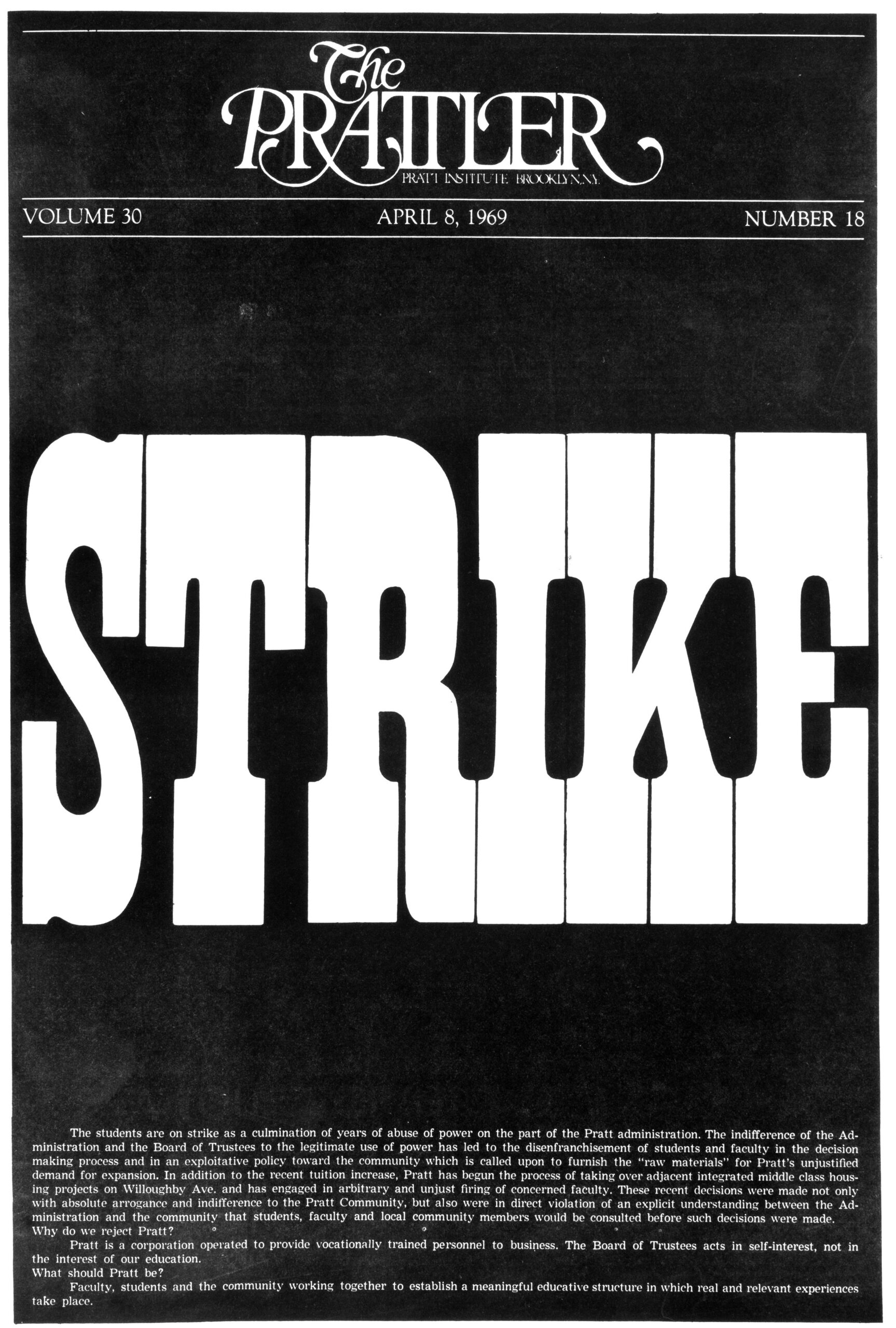

Archives graduate assistants Miranda Siler, MSLIS/MA History of Art and Design ’22, and Nicole Marconi, MSLIS ’21, collaborated with Preserving Activism research fellow Amber Colón, BFA Communications Design ’23, to create the Pratt Libraries’ first digital exhibition, Protest at Pratt, in 2020. The exhibition details student activism at Pratt spanning the late 1960s and early 1970s—from their participation in the International Student Strike against the Vietnam War on April 26, 1968, to community initiatives organized by the Black Student Union, including workshops to introduce local high school students to the college admissions process.

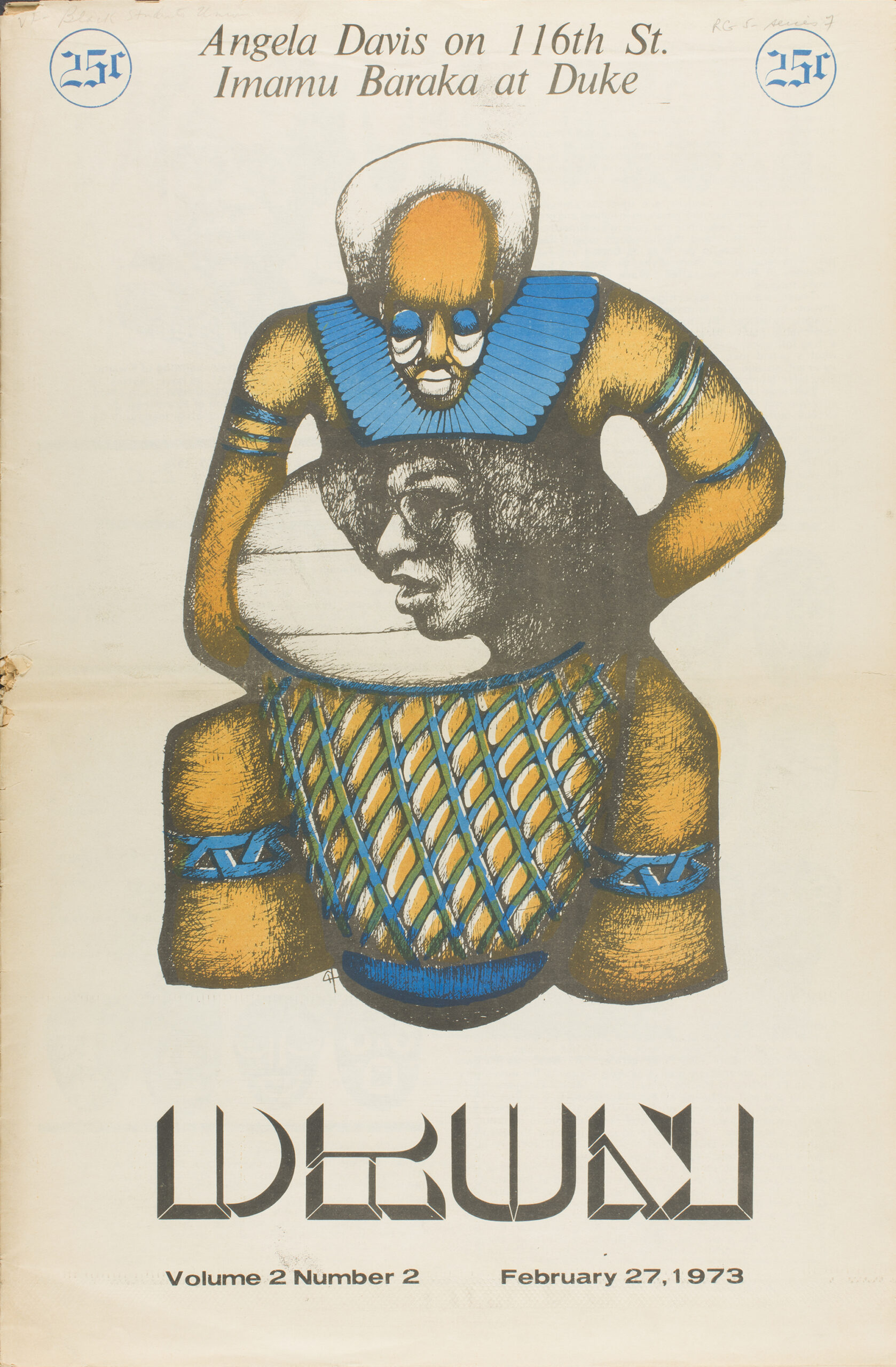

Drawing on oral histories from Pratt alumni, research by Kaitlin Millen, BFA Art and Design Education ’19; MS Art and Design Education ’20, takes an in-depth look at the origins of Pratt’s Black Student Union (BSU), their publication Drum, and the demands the organization put forth in 1972 that championed change on campus and beyond. As part of Preserving Activism’s mission to make these stories public, this project’s digital presentation includes the recorded and transcribed oral history interviews of Pratt alumni Pat Cummings, BFA Communications Design (Illustration) ’74; Connie Harold, class of 1975; and Larry Provette, class of 1972, among others.

Pratt Institute: A Social Experiment

This project by Anisha Kar, MS Historic Preservation ’21, explores Pratt’s 1887 founding and early history with a particular focus on founder Charles Pratt: his ideals, philosophical perspectives, connection to Progressivism, and the values that guided his vision for Pratt, and that continue to influence the Institute today. Drawing on resources from Pratt Archives that include Charles Pratt’s diary, memorandums, and speeches, this research showcases Pratt as an advocate and champion of inclusive education: “I want to found a school that shall help all classes of workers, artists, apprentices and homemakers, and I wish its courses conducted in such a way as to give every student practical skill along some definite line of work and at the same time reveal to him possibilities for further development and study.”

Arresting images by Marc Weinstein, BFA Photography ’74, of local young people building rockets, making art, and exploring cultural hot spots like the Studio Museum in Harlem ignited Preserving Activism researchers’ investigation into the lesser-told history of Pratt’s summer youth programs. Weinstein had worked with Horace Williams, an alumnus and Pratt staff member, to document the early ’70s programs, which Williams established after listening to the Black Student Union’s call to action to create access to Pratt’s educational resources for the local community. This research culminated in a photography installation—in collaboration with Myrtle Avenue Brooklyn Partnership—across seven Myrtle Avenue storefronts in spring 2022.

Maps; streetscape photographs; an oral history with city planner Ron Shiffman, BArch ’61; MS City and Regional Planning ’66, cofounder of the Pratt Center for Community Development; and other materials, compiled by Rofidah Alhumaidi, MPS Arts and Cultural Management ’22, help clarify the City-sponsored urban renewal plan of the 1950s and ’60s that significantly impacted and forever changed both Pratt’s campus and the surrounding area. What was the background of this urban renewal plan? Who were the key players involved? How did that activity shape the activism era that followed? These are just some of the questions this area of Preserving Activism research aims to address.

Research being undertaken this year by faculty members Heather Lewis (Art and Design Education) and Keena Suh (Interior Design), in collaboration with community partner 7Cinema, highlights the 1969 removal of the Myrtle Avenue El, the 1970s fiscal crisis’s effects on public transportation, and the impact of the BQE on community life. The project, Long Memories of Material Injustices: Central Brooklyn Elders Speak about Inequitable Transportation Access, which received the support of a Taconic Fellowship from the Pratt Center for Community Development, includes oral histories documented by 7Cinema—where Pratt graduate Alan Minor, MS City and Regional Planning ’18, is a partner—and unconventional archival practices related to memory, to capture the accumulated history of discriminatory policies and practices around transportation. An exhibition of this work, Elevated Voices: Elders Speak of Transportation Access is on display at Khim’s Market on Myrtle Avenue through the end of May 2023.