With humanity, compassion, and courage, Pratt alumni are changing culture, altering the landscape of the world for the benefit of others. Patients can access more effective care, communities that have experienced injustice grow stronger, and citizens find means to speak truth to power and reimagine society because of graduates’ notable contributions to industry and culture—work that wouldn’t be possible without endeavoring to understand experiences beyond their own. The 2018 Alumni Achievement Award winners, who were honored at Alumni Day in September, share their thoughts on the human resonance of their diverse work.

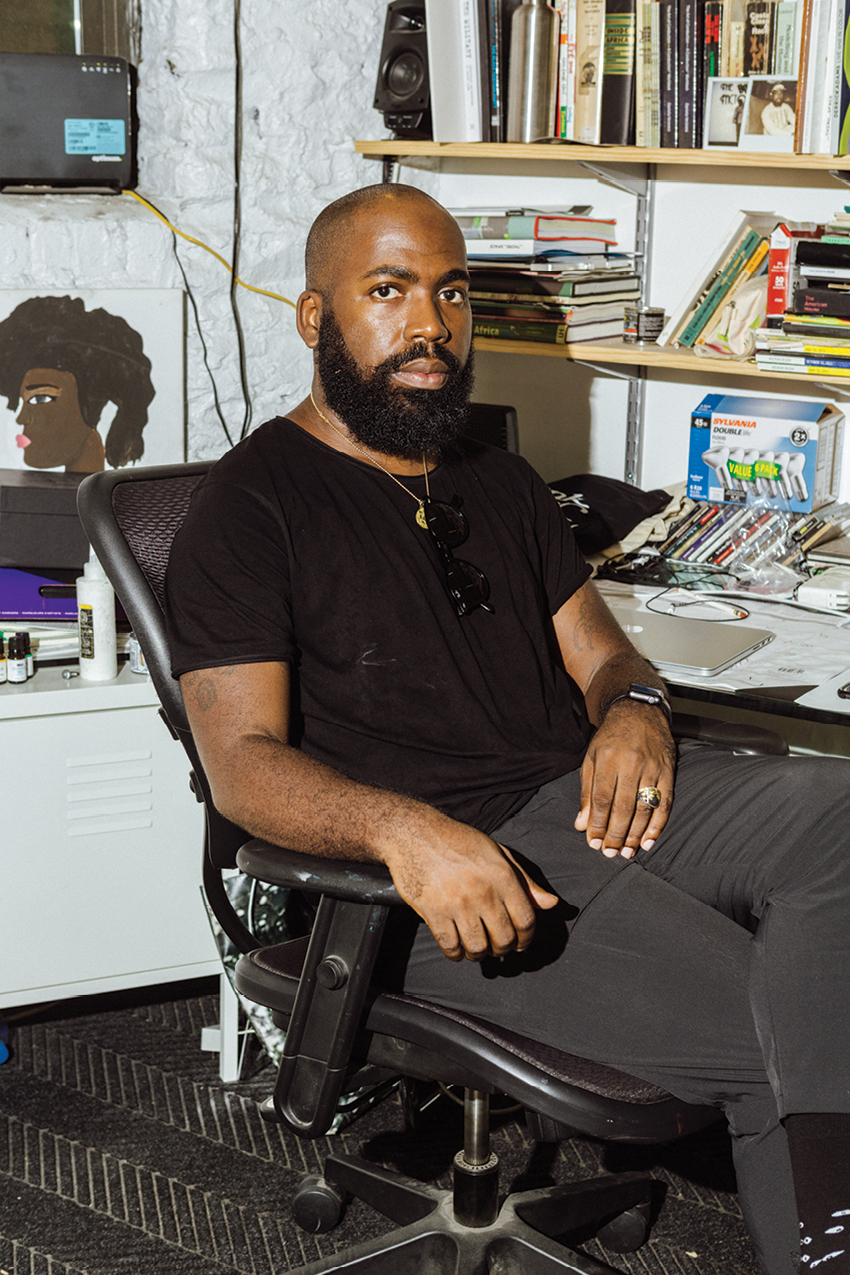

Derrick Adams, BFA Art and Design Education ’96

Derrick Adams is a Brooklyn-based artist working in an expanse of disciplines, with a practice rooted in fragmentation and manipulation of structures and surfaces to examine how popular culture and media messages inform the images we create of ourselves. Adams is renowned for his work exploring the nuances of the black experience, most recently through his multimedia exhibition Sanctuary, which used a series of travel guides written by and for black Americans in the mid-20th century as a departure point for his explorations of accessibility, barriers, and what it means to have freedom to move.

How do you see empathy functioning in your work?

My work draws inspiration from humanity in general, and black Americans specifically. Given the inequity and injustice against people of color in America and the world, the very act of making work with the black subject brings us into the consciousness of those who view it—what shifts take place in the mind of the viewer are unknown. I make work of people like myself at leisure as a testament to the fact that throughout struggle there is also a time for rejuvenation, play, and reflection. It is necessary to see a complete picture of black people and not just images of oppression and violence. Only by seeing us as whole can understanding be achieved.

Is there a project that has particularly underscored the human resonance of your work?

My show Sanctuary at the Museum of Arts and Design here in New York was inspired by The Negro Motorist Green Book, an annual guidebook for black American travelers published by New York postal worker Victor Hugo Green from 1936 to 1967. I wanted to make work about this person who indirectly saved people’s lives by doing something so simple yet so profound. Mr. Green compiled information from across the country as a guide for safe places to eat, sleep, get gas, shop, etc. during an era when open and legal discrimination was widespread. Seeing what is happening in our country and world today, it felt important to make this show so audiences can compare the similarities and hopefully take positive action.

What advice would you give to young artists seeking out ways to generate understanding and awareness of others’ experiences through their work?

Look around you. Look at yourself. Look at others and see what they are going through. Ask what is important, what is urgent, what is missing. Present practical ideas showing us how we can be better. To present others in the hopes of generating understanding, you really need to understand their experiences, which can be a difficult task depending on where you are coming from. The key is to know that understanding other people’s struggle does not detract from what you are going through; try not to compare.

Mahogany L. Browne, MFA Writing ’16

Mahogany L. Browne is a writer, organizer, and educator known for her bold works of performance poetry and her activism. Currently the artistic direction of Urban Word NYC, a youth literary arts organization, Browne came up in the world of slam and spoken word, deftly weaving the personal and political in her work. Browne is the author of several books, including Redbone, nominated for NAACP Outstanding Literary Works, and the best-selling illustrated book Black Girl Magic (Roaring Press/Macmillan), and she recently coedited The BreakBeat Poets: Black Girl Magic anthology. During her time at Pratt, Browne founded the Women Writers of Color Reading Room and produced two years of social justice and arts programming for Black Lives Matter at Pratt.

How do you see empathy functioning in your work?

I see empathy breathing throughout my pieces because they require humanity to be considered. I’ve been investigating what is goodness and what is “bad,” and it’s required that my moral compass takes a backseat and I truly observe human behaviors. How does jealousy show up? What does lack of attention as a child manifest as in the adult body? When is capitalism worth our community’s financial stability and how are cultures decimated because of it? And rather than ask who’s to blame, I am trying to ask, what does support look like?

Is there a project that has particularly underscored the human resonance of your work?

My last couple of years’ work asked me to investigate the ripples of domestic violence, cultural assimilation, and effects of mass incarceration. I am currently diving deeper into the research as a child of a victim of the mass incarceration system, so I feel like I’m truly just getting started.

As an educator, how do you guide your students as they attempt to use their voices to confront those challenges with wide ripples beyond their own experiences?

I am always holding up the mirror and the microphone. The people I work with are often reminded they should be silent. They are awarded for this behavior. And when they speak up against atrocities, there is some tension. Through writing, we release the tension. We’re able to name it and reclaim our space in the room, in the world. I also remind folks that if we don’t write our own stories, who will speak up for us? This kind of action reminds them of history, how inaccurately our stories are retold when we aren’t the authors of our own memories.

Thomas J. Hughes, BME ’65; MME ’67

The body has its own mathematics—and what if solving the right equations means saving lives? It’s a question Thomas J. Hughes has pursued since his early days as a researcher, and now one of the most widely cited authors in computational mathematics and engineering science, Hughes has devoted much of his career to engineering improved resources for patients at risk of life-threatening disease. Among his notable contributions is laying the groundwork for HeartFlow, Inc., which developed a patented cardiac test that analyzes blockages and blood flow in cardiac patients without invasive procedures.

How do you see empathy functioning in your work?

Empathy is the driving force behind the areas in which I choose to work, the problems in these areas that I attempt to solve, and with whom I choose to work—for example, in the area of cardiovascular disease. It may seem strange that an engineer would be working on such problems, but in recent years there has been a confluence of technologies and disciplines brought to bear on medicine. When I was about to choose a PhD thesis topic, I heard about initial work in the new—at the time—field of biomechanics, in which mechanical ideas were used to study problems of orthopedics and blood flow. My father died when I was nine years old of a “heart attack,” but I didn’t really know what those words meant. He suffered for years before he died, and I wanted to know more about this illness and to eventually do something about it. The thesis topic I chose was motivated by this—namely, blood flow in arteries. It was very mathematical and perhaps ahead of its time, but it set the stage for my future involvement in medicine.

Is there a project that has particularly underscored the impact of your work?

In 1994, during the time I was on the Stanford University faculty and also had an engineering company, the university’s new chief of vascular surgery, Chris Zarins, came to see my company’s computer simulation technology. It was all devoted to traditional engineering products, so the only thing I had that I thought he could relate to was a garden-hose problem that looked a little bit like an artery, but it was squirting water all over the place and seemed like a vascular surgery gone awry. I had no idea what his reaction would be and I became a little worried. He stared at it for what seemed an eternity and then turned and said to me, “This technology is going to revolutionize vascular surgery.” That was the beginning of a collaboration and friendship that have gone on ever since. Chris and our first graduate student, Charles Taylor, cofounded HeartFlow, Inc., which has commercialized a computer-based, patient-specific, noninvasive procedure for precisely diagnosing coronary artery disease that replaces risky invasive procedures still in current use, at lower cost and with better patient outcomes.

What advice would you give to young engineers seeking out ways to improve others’ lives through their work?

Most of the young engineers I work with are advancing toward PhD degrees that will prepare them for research careers. They typically have very strong technical backgrounds and possess skills in mathematics and computing that could be exploited on a wide variety of problems. As they are coming to the end of their studies and thinking about the future, they often ask me about what direction they should pursue. I usually say something like this, “Cardiovascular disease and cancer are the number 1 and number 2 killers in the US, and worldwide, respectively. Pick one.” Often, they question whether they have the necessary background, but smart people can learn anything, and modern research is multidisciplinary and team oriented. They have the ability to bring unique skills to the subject and often the talent to really make a contribution.

A final note: I practice what I preach. I am also now working on prostate cancer, which I became interested in after a good friend died from it.

Pascale Sablan, AIA, NOMA, LEED AP, BArch ’06

A rising talent in the field of modern architecture inspired by urban narratives, Pascale Sablan takes inspiration from today’s city landscapes and their inhabitants, as well as the quiet strains of history that might otherwise be drowned out by more dominant voices. Representation and voice are at the heart of Sablan’s practice, which has seen her contribute her expertise to the African Burial Ground National Monument, the first black slavery monument in New York City; help redesign a Haitian school campus destroyed in the country’s 2010 earthquake; and most recently, curate the exhibition SAY IT LOUD, a showcase at the Center for Architecture and the United Nations in New York City featuring more than 20 distinguished minority designers.

How do you see empathy functioning in your work?

There are 109,748 licensed architects, and 2 percent are African American. Those 2 percent faced many obstacles and persevered, and some contributed greatly to the built environment. However, due to the forces of erasure in both the education system and profession, their work and their existence are rarely recognized. I feel empowered to protect, elevate, and proclaim their contributions. Most of my work is shining light on others to inspire a more diverse profession in the future.

Is there a project that has particularly underscored the human resonance of your work?

The Haiti Campus is a project I collaborated on with students in the ACE Mentor Program [a national program for young people pursuing architecture, construction, and engineering careers]—a unique opportunity to join two of my passions: mentoring and design. We worked together to redesign a school, in Cap-Haïtien, Haiti, for the Association of Haitian Physicians Abroad organization, whose school campus in Port-au-Prince was destroyed in the 2010 earthquake. Incorporating educational, support, and community functions, the campus is now able to house 1,500 students ranging from elementary to high school, withstand earthquakes and hurricanes in the flood-prone area, and create a resource that ties into the existing fabric of the community.

What advice would you give to young architects seeking out ways to improve others’ lives through their work?

Wholeheartedly join organizations and participate in initiatives and programs that address an issue you feel passionate about. This will help you immediately make an impact. It will educate you on many facets of the issue as well as expand your network to like-minded and motivated professionals who also are passionate about the cause. You do not need to invent the wheel. Support one another and make an impact.

Tucker Viemeister, BID ’74

Tucker Viemeister thrives on the collaborative exchanges that make meaningful, lasting design. Since cofounding Smart Design in 1979, he has gone on to lead teams at such firms as frogdesign, for which he launched the New York City office; Razorfish; Thinc; Ralph Appelbaum Associates; and Rockwell Group, where he founded the Lab. Known for his OXO Good Grips ergonomically designed kitchen tools, iterated through dozens of models to best serve users with a range of abilities, Viemeister has been a forerunner in design that prioritizes both accessibility and aesthetics. His latest project, with Shanghai studio Xenerio, sees him helping to bring complex science to a broad audience in the planning of a new planetarium in China.

How do you see empathy functioning in your work?

Empathy is a prerequisite for any designer because design is a back-and-forth project. Designers need to understand the clients, the manufactures, the workers, the materials, and especially the user. User-centered design is not solving the users’ problems—good design is about creating opportunities in the whole ecosphere. Instead of climbing Maslow’s hierarchy of needs one layer at a time, industrial designers are always trying to achieve all levels at once—function, safety, meaning, and beauty. It’s not possible to actually live someone else’s life, and it’s very easy to apply your own assumptions that may tangle with reality, so to be really sympathetic, you need to always probe the boundaries of your own empathy—beyond the comfort zone.

Is there a project that has particularly underscored the human impact of your work?

Empathy is a moving target—cultural ideas about human relationships are evolving at the same time technology is adding new dimensions. I’m working on a conference [which took place in September at the Japan Society] whose theme is empathy—it’s about how advances in digital-sensing technology are affording new avenues for empathy and what human relationships mean to artificial devices.

I’m also working with Xenario on a huge new planetarium in Shanghai, China. We are designing the exhibitions to help people understand the universe and inspire further exploration and discovery. We are attempting to present some of the biggest questions, scales, and ideas in ways accessible to people of all levels of understanding—this requires a gigantic level of empathy!

What advice would you give to young designers seeking out ways to improve others’ lives through their work?

Here’s what I say to all designers: Your work is really important! You can’t just “be true to your work.” The things you make will shape other people’s behavior. Designers may think their talent is what’s important—but actually empathy is more important. Empathy is a key ingredient of user-centered design, making the world more beautiful and society more civil. Form and function are one when the design is beautiful—that’s why I coined the word beautility. It’s something I learned at Pratt from my teacher Rowena Reed Kostellow, one of the founders of the industrial design pedagogy. As she told us, “Pure, unadulterated beauty should be the goal of civilization!”

Margot Williams, MSLIS ’80

Margot Williams’s work restores humanity to lives affected by structures of power around the world. Her career at The Washington Post—where she was part of two Pulitzer Prize–winning teams—The New York Times, NPR, and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists is one of the most respected in the investigative-reporting world, with research that has shone a light on civilians who lost their lives in police shootings in Washington, DC, and terrorism suspects sequestered in an international network of secret prisons. Currently research editor for investigations at The Intercept, Williams reports on national security and surveillance for this news outlet specializing in deep-digging, justice-minded journalism.

How do you see empathy functioning in your work?

My favorite quote about journalism comes from the newspaper reporter played by Gene Kelly in the 1960 film Inherit the Wind: “It is the duty of a newspaper to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.”

A newsroom is a team effort internally and a public function externally. Empathy figures in both. In the newsroom, researchers and reporters have to support and engage with each other in order to succeed. This is especially true in investigative reporting, which is a collaborative process. As a news researcher, throughout my career I have primarily worked in teams and partnerships, in the news library and on breaking news, data dives, and investigative projects.

Externally, news research and journalism aim to help people and hold government accountable. To do this consistently and objectively, you have to empathize with the plight of others, at home or abroad. Journalism is a humanistic profession.

Is there a project that has particularly underscored the human resonance of your work?

In January 2002, the first detainees landed at the detention camp at Guantánamo, and they were prisoners without names until 2006. I set out to find out who they were and how they got there. At The Washington Post and later at The New York Times, NPR, and The Intercept, I have continued to collect, research, and publish data on these men, which can be seen at The Guantánamo Docket interactive database of documents and analysis on the New York Times website.

I have been to Guantánamo three times and have met with families of the 9/11 victims as well as the defense attorneys for the men accused of the terrorist attack. Every person caught in a secret system of kidnapping, detention, and torture was a human being. Some had committed heinous crimes and deserved punishment. Many more had committed no crime at all. I could relate to the innocent ones, and that gave me the determination to account for them all.

What advice would you give to young people seeking out ways to use data to tell important stories and generate greater understanding?

Develop expertise in a subject area involving people you are passionate about. These could be people very much like you or people who are very different. Understand why you care about them and why you want to tell their story.

Develop the technical skills to organize and analyze your reporting. I’m proud to be a data nerd. Girls can do math and women can be data journalists. My Pratt MSLIS degree showed me I could do it.

Don’t lose hope. We live in terrible times, where delusion and deceit are ascendant, but that can change. It has before, thanks to people who tell new stories that make new sense to the world, people like you.

This article was originally published in Prattfolio (Fall/Winter 2018). Read the issue at www.pratt.edu/alumni.