When entering a creative field, it’s only natural to seek out the wisdom and work of predecessors whose experiences resonate with our own. But what happens when those voices are more rare, hidden gems than the crown jewels of the canon? In 2018, when Farah Kafei and Valentina Vergara were in their thesis year at Pratt, they launched a significant project to amplify the work of fellow women graphic designers after finding a dearth of representation among the dominant figures in their discipline. The campaign, titled Led by Example, advocated for more women in positions of influence—as educators and mentors, and in the history books. As part of the project, an exhibition hung in Pratt’s Steuben Hall, Missing Pages, took steps to build that dream textbook, presenting research on women designers working from 1900 to the present, and an accompanying panel of industry pros created context for and expanded that conversation. It was at that panel that the seeds of an actual book were planted.

This May saw the release of Extra Bold: A Feminist, Inclusive, Anti-Racist, Nonbinary Field Guide for Graphic Designers (Princeton Architectural Press), which Kafei and Vergara coauthored with design luminary Ellen Lupton and a team of designers coming to the profession from a range of backgrounds. It’s a career companion with elements of zine, comic book, and how-to manual that sheds light on how diverse designers are experiencing and shaping the profession, with a wealth of advice for emerging practitioners. As the book hit shelves, a few years out from Pratt and into their careers as graphic designers, Vergara and Kafei connected with Prattfolio to discuss some of the themes woven throughout Extra Bold—mentorship, working with care, and how design is progressing into the future.

Extra Bold touches on mentorship as a topic—and the book as a whole reverberates with mentor energy. What qualities have you sought out in your mentors?

Farah Kafei: I love that you’re describing it as big mentor energy, because that’s exactly the role I think we were originally interested in filling. Mentors have not been so easy to come by for us, which is one of the reasons Valentina and I felt the need to organize the panel discussion our senior year. We wanted a chance for ourselves and our classmates to actually hear from, ask questions to, and connect with women in the field. We were lucky enough to continue our relationships with two of the four panelists, and they became mentors—one of them being Ellen Lupton, who then approached us to collaborate on Extra Bold. All of that to say, there needs to be a connection and mutual trust and respect for it to work. I’ve found that that matters more than the type of work they do, or other more practical qualities.

Valentina Vergara: I think the most authentic mentorships I’ve had are not those I sought out but fluid relationships with kind and open people who were willing to be candid with me. I feel that this mostly happens with someone who respects me as their peer and wants to see nothing else other than to see me grow.

What is a valuable piece of advice that’s influenced the steps you’ve taken in your career?

VV: My high school teacher once said to me something along the lines of life is going to take you in different paths, just be open to it. I remember it being a scary thought at age 18, but it’s actually really liberating to not put pressure on yourself to just stay in this one lane.

FK: Hmmm. I have a really bad memory. By bad, I mean I’m only thinking of things I wish I hadn’t heard. A recent quote Valentina and I keep coming back to is from the artist Carrie Mae Weems’s commencement speech at School of Visual Arts in 2016, another tumultuous year. She says, “Who will control your production, who will define you, who will control your energy or time? Will it be another force, or will it be you?” I’d like these questions to guide my next steps.

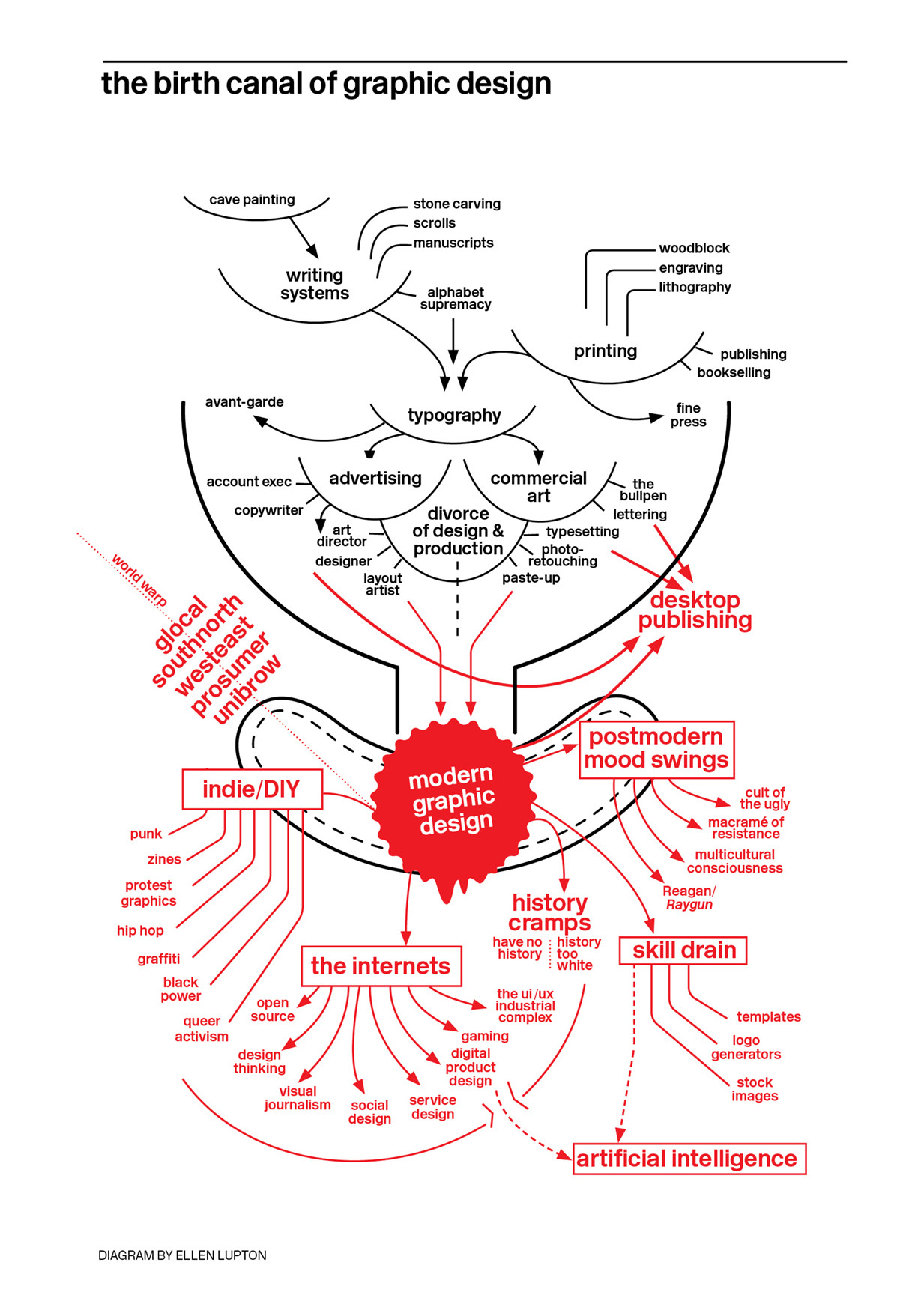

Diagram by Ellen Lupton from Extra Bold, published by Princeton Architectural Press. Used with permission of the publisher.

In the book, Valentina remarks, “Society often pits women—and marginalized people in general—against each other,” but “there is power in numbers, and uplifting and empowering each other is the best way to begin to dismantle this extremely flawed system.” As we move through this time of collective urgency to rebuild broken systems, how do you see systemic flaws being rethought in your area of the industry? What opportunities do you see for the future of graphic design?

VV: I think we are collectively approaching the future with a more critical lens that demands a more equitable industry. A lot of work is being done toward decolonizing established design principles and rethinking the canon of design—which for so long has erased the contributions of marginalized communities and has centered whiteness above all. But needless to say, systems are pervasive and embedded into our society, and rebuilding a broken one is a heavy task.

But I do think we all have the opportunity to restructure this industry. Our work has tremendous social and cultural impact, and I think we are already moving away from a career-oriented mindset into focusing on projects with purpose. I think the future of graphic design is way more fluid, and with a non-linear trajectory it can be way more accessible and inclusive.

FK: I definitely wished and hoped for there to be a greater sense of urgency from the industry after this year, but it feels like for many institutions and companies it’s been business as usual. They have a lot of power and are doing very little, therefore placing the responsibility on each of us, individually. But like Valentina said, there is power in numbers. And there are a ton of incredible individuals doing incredible things together.

A few tangible, recent examples that I’m inspired by are: workers unionizing and securing a more equitable future at the Walker Art Center (Walker Worker Union); generous designers and illustrators quickly organizing and donating time for urgent causes, like the beautifully illustrated and collaborative New York City cookbook that raised $40,000 to help service workers hurting financially from COVID-19 (Family Meal), and a print sale that raised $50,000 in aid to Beirut after the August 4 explosion (Beirut Editions); a creative studio with a nonhierarchical structure that became worker-owned (Partner & Partners).

An example of a more industry-wide norm that’s being dismantled are unpaid internships. This form of gatekeeping is becoming less and less common, which is exciting! It means folks in any financial situation can get that important experience. So there are definitely wins. I’m hopeful that the future of graphic design will be inclusive, innovative, and impactful.

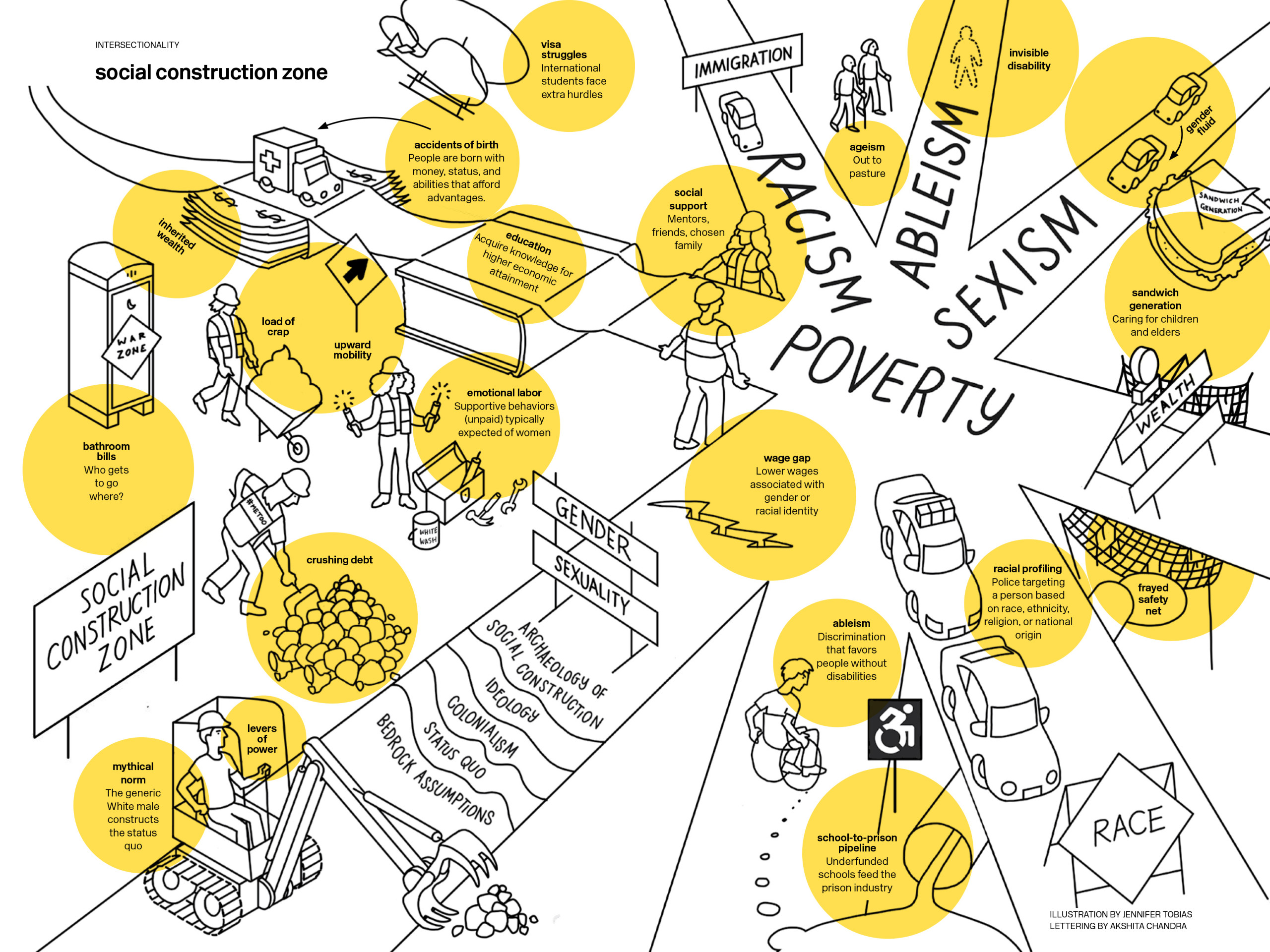

From Extra Bold, published by Princeton Architectural Press. Used with permission of the publisher.

On a more personal level, how have the events of the past year changed the way you think about your work?

VV: Honestly, the events of the past year really reminded me that the work I do has social and cultural impact. Post-graduation, my main goal was to get financially stable and find a well-earning job. But having that constant pressure of making money made me forget about my purpose. It is something I am currently working on.

FK: Ooof. This is a loaded one which I could speak on for hours. Boiled down, your job should not be your life, and if it is, it needs to be absolutely worthwhile. Because life is just too short! And the world needs more creative energy going toward important stuff.

The theme of this issue of Prattfolio is Care. How do you see care integrating into your practice or your path?

FK: Care for me looks like doing the work. Having a critical mindset—I care enough to have hard conversations, to stand up for myself and others, to put carefully considered attention to what I help clients put into the world, acknowledging the social responsibility and impact it has. At least I’m trying my best to do this!

VV: Right out of college, I quickly learned that care needs to be at the center of my path. Specifically, taking care of myself to be able to care for others. It’s so easy to get caught up in a lifestyle where you prioritize work over your own health, but you should always come first. Surrounding yourself with people who care about you is also so important because it allows you to have the space to grow. To me, success comes easier when you learn to value care and compassion over material advancement.

-

![Headshot of Farah Kafei, with long dark brown hair, a white T-shirt with partially covered red lettering, and long gold earrings, leaning against a wood wall]()

Farah Kafei, BFA Communications Design ’18

-

![Headshot of Valentina Vergara, with dark brown and teal curls, silver chain and hoop earrings, against a rose and lavender gradient background]()

Valentina Vergara, BFA Communications Design ’18