How can reimagining a historic space help communities to heal and to shape their future?

Pratt Institute students in one advanced studio offered jointly by the master’s programs in Historic Preservation and Urban Placemaking and Management explored this last fall as they worked on a project to activate Lefferts Historic House in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park for neighbors and new audiences. Their work would confront the realities of the house’s colonial past alongside the ongoing dispossession affecting communities in the surrounding area and position the site as a space to support healing for those in the local community whose lives have been affected by racial, cultural, and economic injustices for generations.

The studio, taught by Graduate Center for Planning and the Environment (GCPE) Adjunct Associate Professor Beth Bingham, MS City and Regional Planning ’10, and Adjunct Professor of Interior Design Jack Travis, built on GCPE’s ongoing work at Prospect Park with Prospect Park Alliance. Working with Prospect Park Alliance as their community partner, the interdisciplinary group of 17 students—from City and Regional Planning, Historic Preservation, and Urban Placemaking and Management—collaborated to research, analyze, and interpret the complex history of the 18th-century structure, built by Black enslaved people for a privileged family on Native American land, and consider how a clearer understanding of that history could lead to changes that benefit the present-day community.

The Lefferts Historic House takes its name from the Lefferts family, who were early Dutch settlers to the region, unceded land that was inhabited by the Lenape people before the arrival of the Dutch. The Lefferts family were also slaveholders.

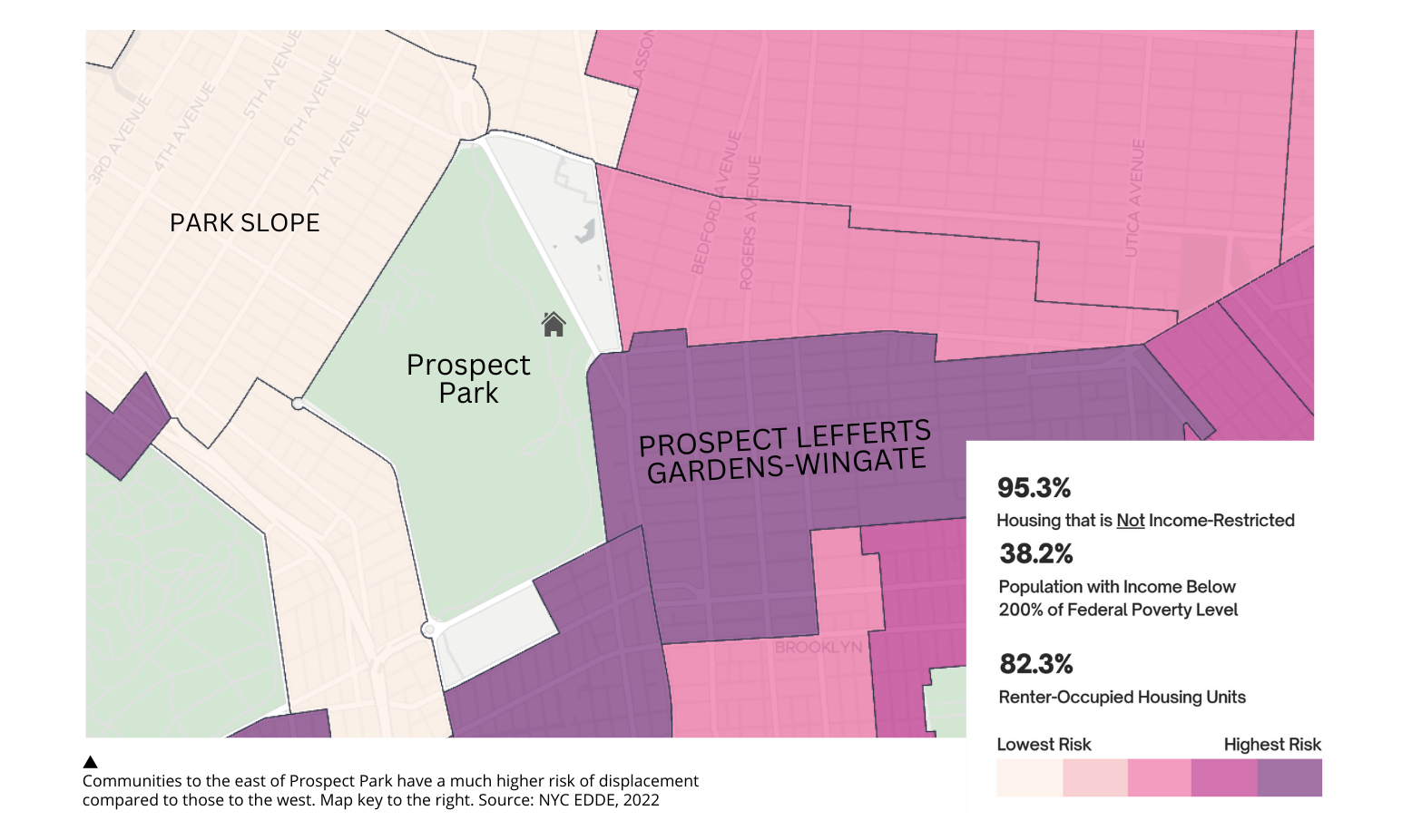

The house, which was moved from its original location on nearby Maple Street in 1917, is situated on the east side of Prospect Park on Flatbush Avenue, adjacent to the neighborhoods of Prospect Lefferts Gardens, East Flatbush, and Crown Heights, a crucible of gentrification and increasing housing pressures, particularly for today’s Afro-Caribbean residents.

Designated a New York City Historic Landmark in 1966, the house, as a museum, has been programmed to reflect the colonial life of the Lefferts family, but Prospect Park Alliance, which jointly manages the site with the Historic House Trust of New York City, has been working to reconsider the house’s story and its role in the community.

This context, along with an understanding of Prospect Park Alliance’s priorities for their community engagement initiative Reimagine Lefferts, would inform the students’ proposals for design interventions that could play a part in “reimagining what the house could be, to recognize its role as a site of slavery, and tell its story in an innovative, inclusive, and forward-thinking way,” as Megan Maize, MS Historic Preservation ’23, said during the group’s presentation at Super Saturday, GCPE’s culminating event showcasing student projects at the end of each semester, last December.

The students summarized those priorities in their final report: to focus on those who lived and worked on the land, to inform visitors to Lefferts Historic House about slavery in New York, to consider the ongoing erasure of Black and Lenape cultures, to connect with diverse audiences on contemporary issues, and to continue active participation with the land.

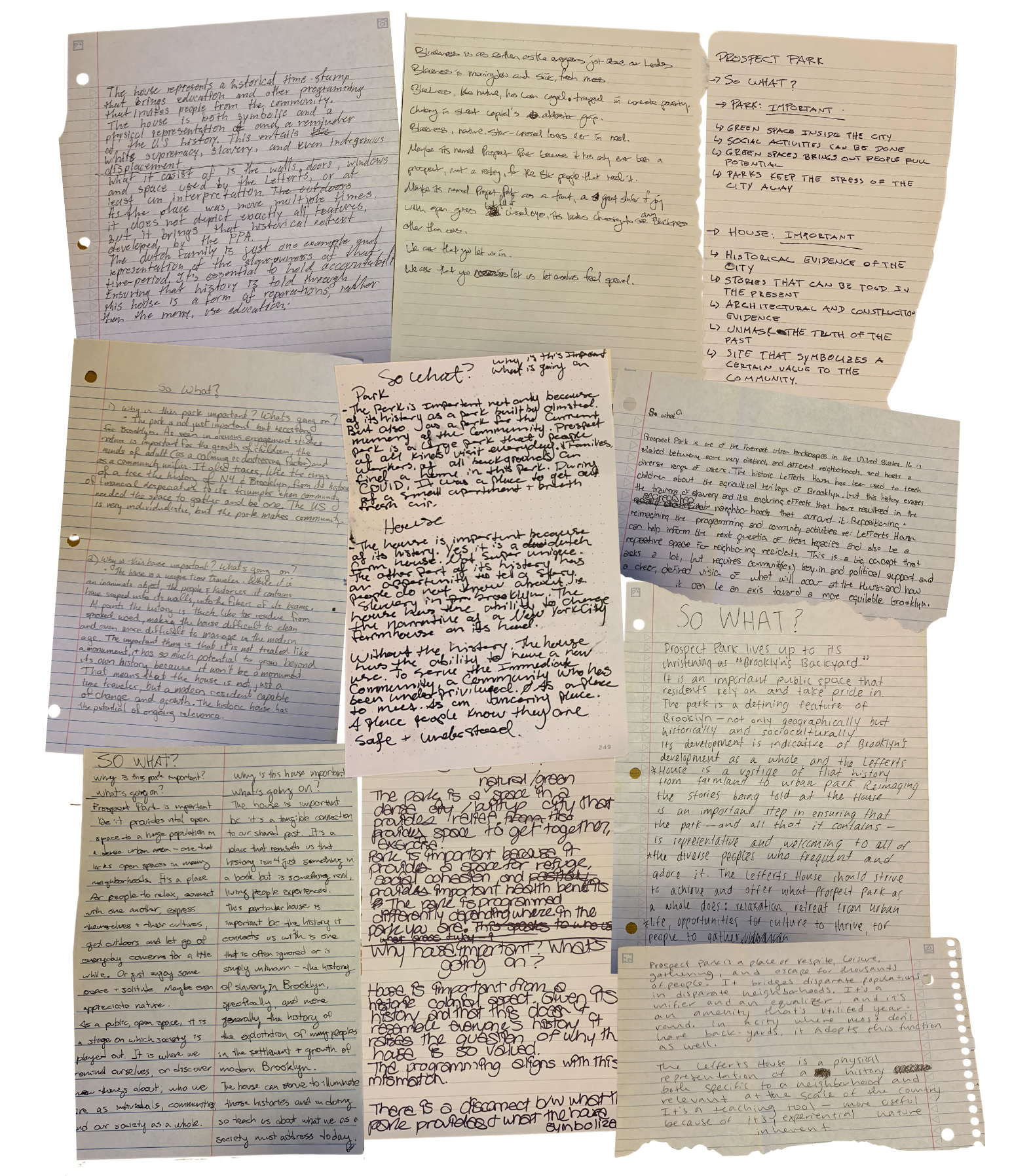

For the exploratory phases of their work, throughout the fall semester, the students embarked on a series of site visits to the house and park and conducted research and analysis on the area and its people from precolonial times to today. They also held conversations with planning, heritage preservation, and community engagement experts as well as, crucially, community members. The group conducted 15 community dialogues, in focus-group and interview formats, with local community board members, residents, and educators, among others.

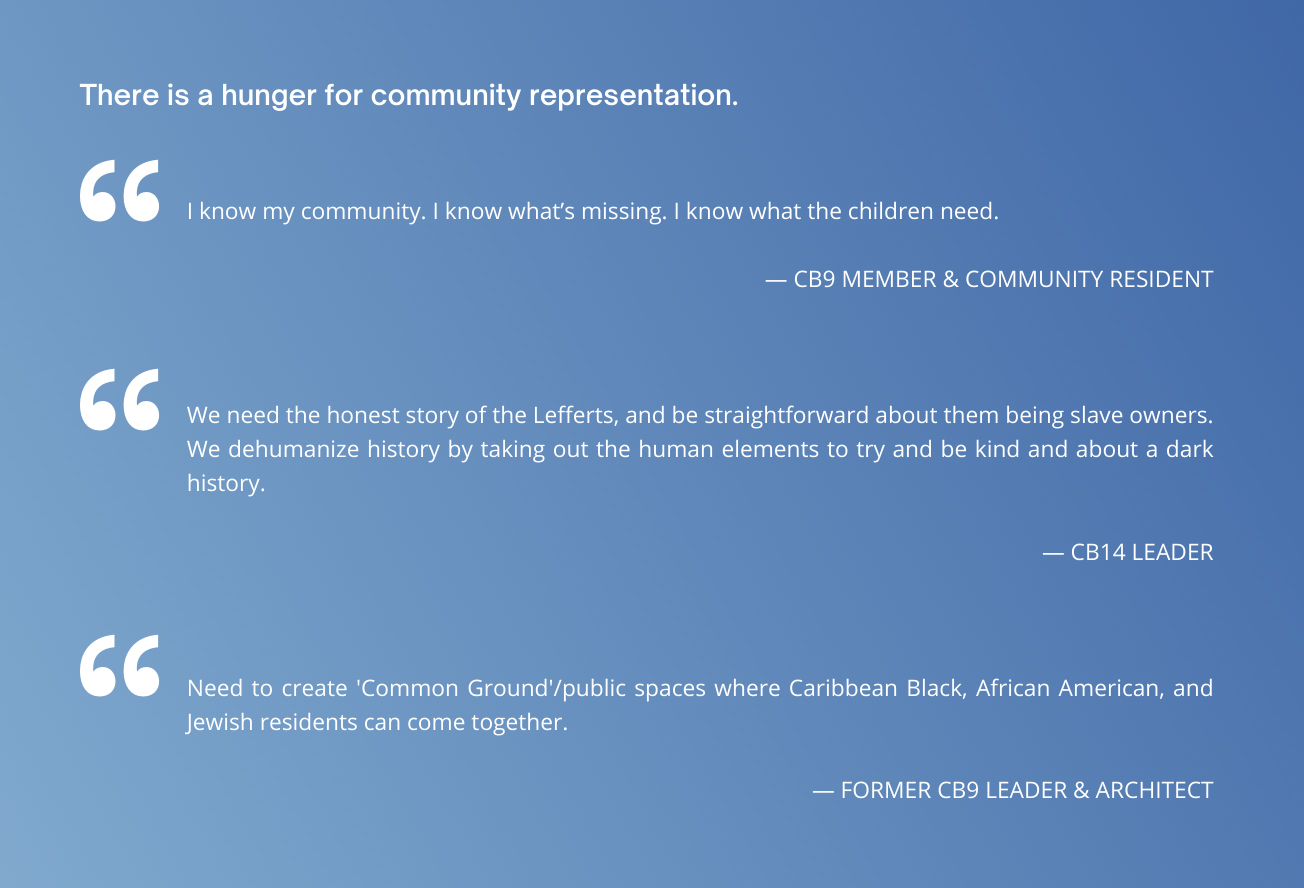

Through that process, the students uncovered community members’ desires for representation, experiences that empower and celebrate humanity, and a more welcoming environment in relation to the site.

Considering how to transform the house from a historical artifact to a space that supports meaningful community engagement, the students acknowledged their challenge: to strike a balance between the stories scholars and professionals might wish to tell and those visitors wish to experience—namely, stories that, while they acknowledge painful realities of the past that continue to weigh on the present, affirm the community’s strength and resilience throughout history and in the moment we are living in today.

“We see the house as a hub of social memory and collective connectivity in the community that isn’t limited to the specific location and timeline of the house,” Maize said. “We want to increase space to dream and imagine new futures while centering critical and silenced narratives rooted in history, through design and programming that fosters deep connection through meaningful dialogue.”

On Super Saturday, the group opened with a poem by Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape writer Opalanietet, commissioned as part of another Prospect Park Alliance initiative, Writing with the Land, whose lines resonate with undercurrents of the students’ work: “Freedom is to roam, freedom is to play, freedom is to choose to stay / To be free with this land, we have no landlord, we have no king, or queen / This land that still is Lenapehoking.”

The design interventions the group developed address the urgent need for community care while honoring the origins of the place and the Lenape and enslaved people whose stories are embedded there.

“We not only propose a way to reintroduce the house to the community,” said Robyn Stebner, MS Urban Placemaking and Management ’23, “we also create another level of engagement that can foster local stories of triumph and inclusion.”

The Projects

Designing Space for Community and Conversation

Displacement, the team observed in their final report, is a throughline that links the past and the present of the site—developed on unceded Lenape land; constructed, reconstructed, and maintained by the forced labor of enslaved Black people; and now, situated adjacent to a crucible of gentrification where today’s Afro-Caribbean communities face increasing housing pressures.

Finding that residents on the east side of Prospect Park, particularly in Prospect Lefferts Gardens, are at the highest risk of displacement compared to other neighborhoods bordering the park, the team considered the house as a potential site of community agency and organization. Looking at the cultural makeup of the study area’s communities, the team’s recommendation “embraces Caribbean culture as an asset that both powers the community and decolonizes the space,” said Jerome Nathaniel, MS City and Regional Planning ’23.

The team drew inspiration from esusu, an Afro-Caribbean community-based savings and loan system—historically key to establishing financial security, and also representative of the power of community-organized systems—for a project they called Susu Space. They developed a plan for programming the house, with a layout and design features to support community workshops, artist residencies, a marketplace, and a small library.

Relatedly, as food insecurity also disproportionately affects residents of the study area, the group also put forth a project that revolved around regular community gatherings. Drawing on the park’s history as a site for shared meals (a contrast to Central Park, which once prohibited picnicking, the group’s report points out), the team envisioned how the house could host conversations and storytelling events around meals, connecting community members and offering opportunities for collaboration with local organizations and food purveyors.

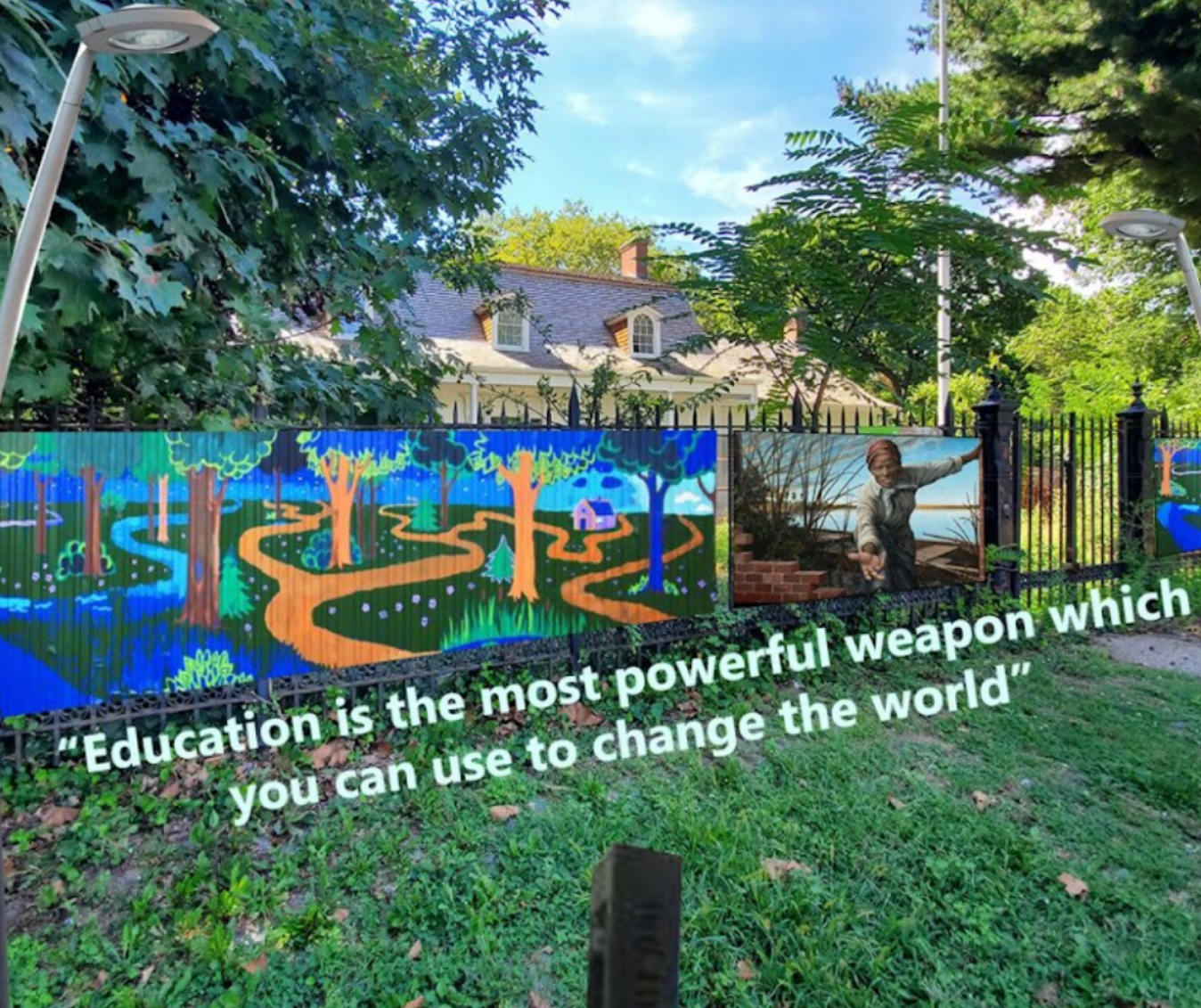

Activating the Street

To get to Lefferts Historic House from Flatbush Avenue, visitors enter Prospect Park through Willink Plaza. The group proposed interventions to energize what is now an expanse of brick and concrete. In addition to safety and accessibility upgrades to lighting, street-crossing signals, and signage, the team proposed the installation of murals and sculpture that reflect local culture and history, along with inviting wayfinding that would welcome park goers and guide them to the house.

Sharing the Story Beyond the Site

Before its closure for renovation in 2019, Lefferts Historic House operated as a children’s museum. In the students’ community conversations, they heard from local residents who vividly recall experiences they had at the museum as children, like churning butter and making popcorn. Bringing those kinds of memorable experiences to a wider community prompted another project that would activate offsite.

During the renovation period, the students reported, Prospect Park Alliance had developed an outreach program called Pop-Up Lefferts, which at the height of the pandemic focused on take-home activities, though ambitions were larger. Listening to the organization’s expressed desire to expand the program, the team considered how the initiative could build upon the house’s on-site programs for school children and reach students in the classroom.

The team suggested an educational program that animated the daily life of different people who once lived at the house or on the land, balancing the harsh elements of history with stories that demonstrate resilience. To help school-age students engage with and process their feelings around the subject matter, the group proposed interactive elements such as a small-scale house model or portable environment to encourage play and expression.

Making Space for Remembering and Healing

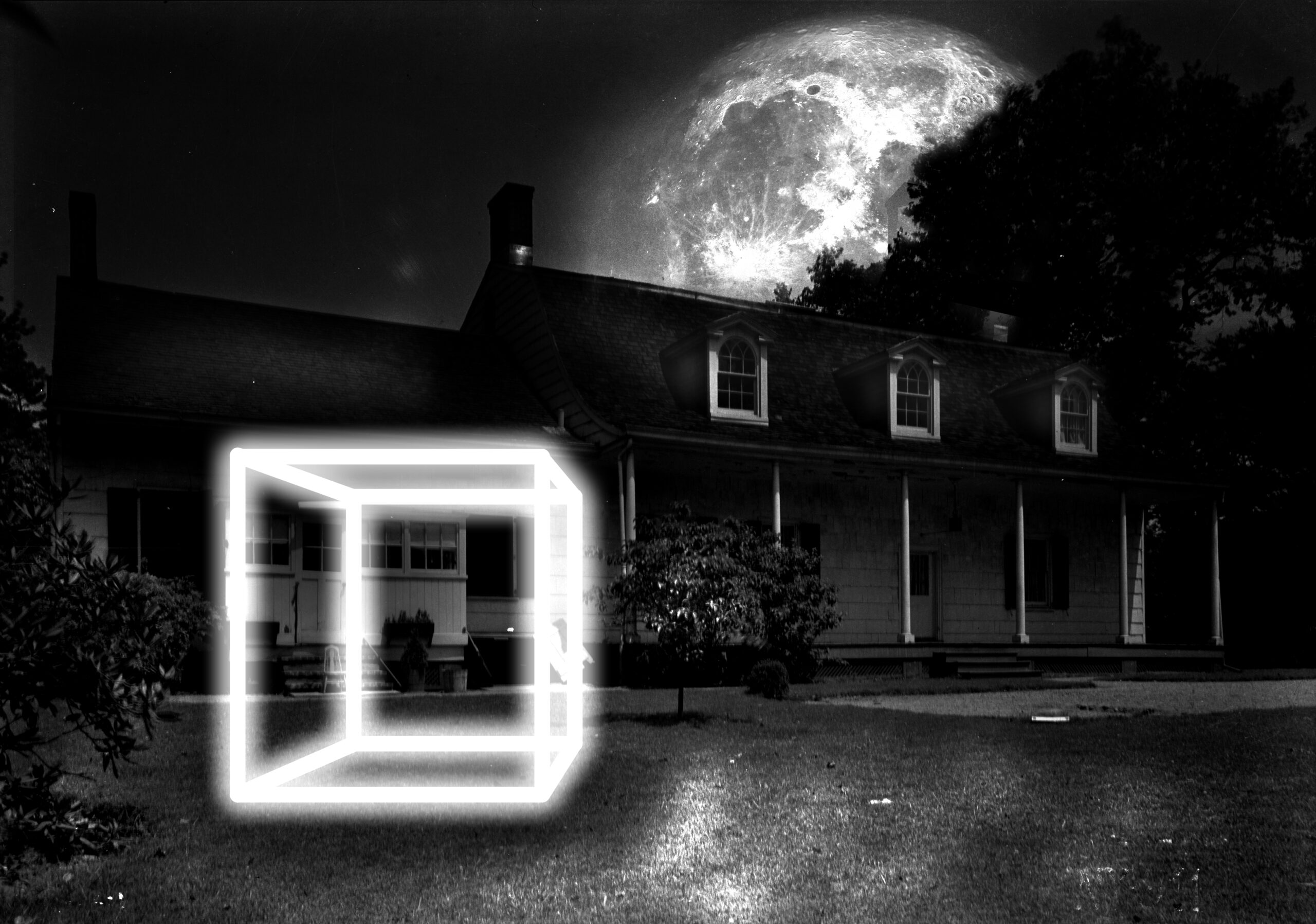

In their site analysis, the group identified several “lost spaces” within Prospect Park once home to structures embedded with stories and context—such as thatched huts that were part of the park’s original design, and a dairy that offered park visitors milk from cows that grazed on the Long Meadow. The Lefferts House itself once had an addition, built in the 1850s, that was removed when it was turned into a historic museum. To draw attention to missing pieces of postcolonial history like these as well as Indigenous landmarks, the group proposed installing a series of sculptural voids—open frames that delineate space—that might invite curiosity and fresh interpretations and spark new conversations about topics that touch today’s local community, like home, migration, and change.

Another recommendation explored wild landscape design using native plants, evoking the space as it was before colonial settlement and offering visitors zones of contemplation and pause to connect to the land and its history. The group also reimagined storytelling around the land, which has previously focused on Brooklyn’s agricultural history, to emphasize Indigenous and Black farmers and growers. In addition to proposals for architectural elements and plantings, the team suggested immersive aural displays that could range from calm-inducing falling water to historical soundscapes.

An Ongoing Plan for Cultural-Heritage Engagement

In their report, the group highlighted Prospect Park Alliance’s intention to locate and contact descendants of enslaved people who lived at Lefferts House and people of Lenape ancestry who live in Brooklyn. To make the most of these potential connections, they recommended a series of steps that might generate long-term public engagement with cultural heritage, including determining the interest of descendants in participating in decision making around the site and forming an advisory council of descendants and Lenape residents, and linking up with other sites that share similar histories to work in concert on repositioning narratives, raising awareness around histories of slavery and Indigenous displacement, and establishing best practices for involving and enriching the community.

To bring closure to their work, the group committed to reporting back to all of the communities they connected with in their research, they said in December. But they emphasized that the overall work is ongoing, and in their observation, there is no single next step. Their most important recommendation for Prospect Park Alliance: to sustain community outreach, and continue to invite new perspectives and opinions to the conversation.

“As a site with a tangible historic legacy located within a major public space in a diverse, dense neighborhood in a prominent city,” the group said in their final report, “Lefferts House presents an opportunity to set a powerful precedent for the ongoing engagement between such a site and its surrounding community.”