As a practice, New York-based architecture studio ChoShields has always been interested in environmental and social sustainability. But it wasn’t until founding principal In Cho, visiting assistant professor in the undergraduate architecture program at Pratt Institute, became concerned about mold prevention in an extensive renovation project the studio was working on that she landed on what she describes today as their “North Star.”

“As I was doing research, I came across Passive House,” says Cho. “Once I started understanding what Passive House was about, I realized it had so many other critical benefits besides just mold prevention.”

Developed by Dr. Wolfgang Feist in the late 20th century, Passive House is a set of five guiding principles for design and construction that not only provides remarkable interior comfort and indoor health, but also has the ability to drastically reduce energy use, by up to 90 percent. Originally created to be used for residences, today it is used for all types of buildings. Able to heat and cool our homes and other structures with minimal energy use, this sustainable building method, which offers environmental, social, and economic resiliency, helps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions produced by the use of fossil fuels, and therefore plays a critical role in the climate solution.

“Our built environment is a huge culprit in the climate crisis,” says Cho, who notes that it is responsible for 40 percent of greenhouse gas emissions globally, and up to 70 percent in dense urban areas like New York City. “So we don’t have the luxury to ignore it.”

Compelled by this sense of urgency, Cho has made it her mission to empower everyone from professionals to kindergartners with Passive House knowledge. First effecting change through policy, Cho was part of a successful initiative to update New York City residential and commercial building codes to make them more stringent. Then she had a light-bulb moment. Cho realized that if she and her team provided the knowledge to actually comply with these policies, they could drive change on a much larger scale. Together with founding partner Timothy Shields, Cho formed Passive House for Everyone, the nonprofit, education-focused arm of their studio through which they aim to spread knowledge of this highly energy-efficient building science to the up-and-coming changemakers.

“Youth today are so passionate about wanting to address the climate crisis, but they don’t always have the tools to know how to address it,” Cho says. “They are the next generation of industry leaders and they are inheriting this crisis.”

Combining creative arts with hands-on learning, Cho has brought her unique pedagogical approach to teaching Passive House to Pratt students. Over the course of the spring 2023 semester, a group of fourth-year architecture students in her advanced design studio not only learned in-depth the five basic principles of Passive House (air tightness, robust continuous insulation, high-performance windows and doors, thermal bridge–free design, and ventilation with heat recovery) but also put their knowledge into action through a project called the Pratt Brooklyn Ice Box Challenge: the first-ever US collegiate design-build rendition of the international Ice Box Challenge.

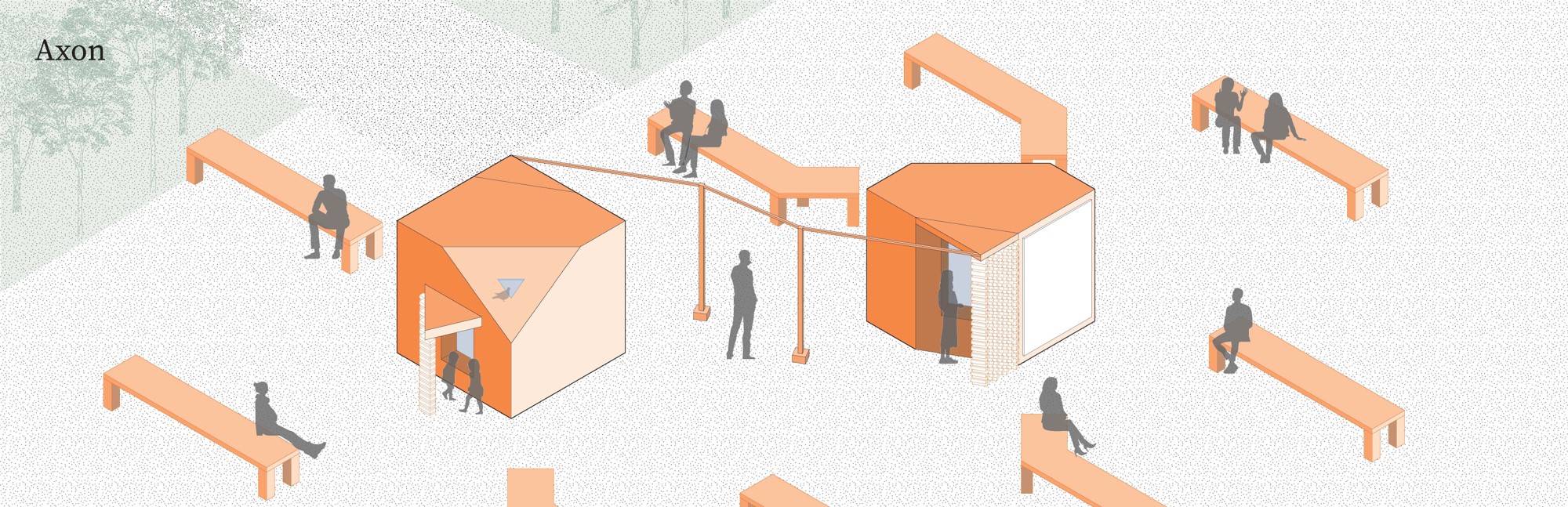

The scientific architectural experiment, first held in Brussels, Belgium, in 2007, and typically done by professionals, invites participants to design two structures, one built to local energy codes and the other to international Passive House standards. A half-ton block of ice is placed inside each of the structures, which are installed together outside, exposed to the sun, on a carefully chosen site. At the end of a specific period—in the Pratt team’s case, one week—both ice blocks are weighed to see which was left the most intact.

“As a student, this experience has been something completely unique and new,” says Maxwell Wolfe, BArch ’24, a student in Cho’s Passive House studio. “Being able to do not only the typical drawings and conceptual thinking, but actually building. Just combining all those skills with new skills.”

The idea of the public demonstration aspect of the experiment is to spread awareness about Passive House as a tangible solution to the climate crisis.

“Passive House at a basic level is the best way to address energy use in buildings, to minimize it, and to therefore address the climate challenges that we have,” says Shields. “We have to give the next generation concrete ways to take on these challenges, and knowing that there are a basic set of principles that you can use to really change the world, gives them, even just mentally, the tools to understand that the world can be changed.”

Before digging into the design-build, students started off the semester embracing Cho’s conceptual, creative arts approach to teaching. They created collages, developed spoken word poetry, and choreographed body-movement explorations to learn the five Passive House principles.

“We asked ourselves, how can we share this knowledge in a way that becomes fun and engaging? So that when students leave our classes they’ll always remember the concepts, because they have a certain personal relationship to them,” Cho says. “When they go through these exercises, they get to fine-tune the nuances of these concepts, to get to a point of real accuracy, which you need, once you get into the architecture.”

The students then split into pairs to develop individual design concepts for the ice boxes, before coming back together as a studio following feedback from a guest jury. Together, they synthesized the elements of their projects that worked best, from the simplicity of the forms to the idea of a second skin that can be customized for context, into the two final 8 x 8 x 8 wood-based structures, each with its own window (triple pane for the Passive House) so curious viewers could peek inside.

Putting into practice the materials and methods of high-performance building construction lessons they learned from various industry and trade professionals over the course of the semester—including Sto-Corp, 475 High-Performance, and Rockwool, who also sponsored the project through donations, along with Klearwall, Passive House Network, Square Indigo, and a number of other industry supporters—the students built and assembled the full-scale structures with their own hands.

“For a lot of us, this was the first time doing a one-to-one scale project,” says Jeremias Emestica, BArch ’24, “as was the experience and learning what it takes to do that—from material takeoffs, construction docs, fabrication, and the huge administrative part of it, because organization was such a key aspect.”

Not only did this build represent a first for a US college campus, but the students’ colorful renditions, one green, one red, both with playful graphics, marked the first-ever modular Ice Box Challenge design. The idea was to make transport and reuse easier so they could pass on the project to other schools and they too could learn about energy-conscious building through this tiny, but very tangible, means.

“This studio wasn’t just about Pratt architecture students learning about Passive House, they’re also learning to be industry leaders, to be able to inspire others, to be social agents of change,” says Cho, “even before they graduate from Pratt.”

This sentiment was shared among Pratt faculty at the Ice Box Challenge reveal on May 8, where, together with the Passive House studio students and Cho, they gathered with Pratt community members, industry leaders, city government officials, and local Brooklyn school groups on a sun-drenched afternoon on the Brooklyn campus to witness the results and speak to the importance and the urgency of the matter this project addressed.

“These structures are a testament to how we need to start building in our future,” said Stephen Slaughter, chair of undergraduate architecture at Pratt. “Teaching the next generation of [architects] what these principles [in sustainability] are so they can go into their own practice or into the firms they’re hired in and be an advocate for this is very important.”

Dean of the School of Architecture Quilian Riano agreed and also spoke to the history of teaching and practicing sustainability at Pratt through “environmental pioneers” like late Pratt faculty member William Katavolos and alumnus Edward Mazria, BArch ’62, founder of Architecture 2030, a nonprofit dedicated to finding climate solutions through the built environment.

Summer Sandoval, policy advisor, clean energy and equity, in the New York City Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice, and an alumna of Pratt, MS Sustainable Environmental Systems ’19, touched on the Ice Box Challenge as an effective means to share the benefits of high-performance buildings.

“This challenge is an amazing example of how we can be thinking about the most pressing challenges differently in a very creative way,” Sandoval said. “This really brings to life solutions that people can see, and that people can feel.”

With its block of ice weighing in at 900 pounds, compared to the 737 pounds of the structure built to local energy codes, the Passive House build was the clear winner.

“Now that I know Passive House as a technique, I am much more inclined to use it,” says Emestica. “I’ve been looking at some of my previous projects and thinking about how I can incorporate Passive House design techniques into those projects.”

One example Emestica gave was a housing project, which he said it would be quite simple to apply the principles to because “creating sustainable and comfortable housing is one of the building typologies that Passive House was designed for.” Another is for a mixed-use restaurant and community center project. “For this space, I know the kitchen and the eating area have a huge ventilation requirement, but the other spaces—the classrooms, the gym—they can be built to more typical Passive House strategies. The kitchens below could have their own dedicated ventilation supply zone, and the top is built to a more conventional Passive House mechanical approach.” He adds, “I just think it’s really important to know that Passive House is an option.”

For Cho, who says for ChoShields, this highly energy-efficient building performance standard is a guiding light for every project—“there is simply no other way to build for us anymore”—it’s always about sharing the knowledge as widely as possible and teaching others how to do the same. Beyond Pratt, her goal is to make teaching Passive House a regular part of the curriculum in architecture and design schools across the nation and internationally.

“Teaching our youth is among the best ways to lay the groundwork for a sustainable future, and educational institutions have the greatest opportunity and privilege to create this cultural shift of climate action that needs to happen in our society,” Cho says, “so that everyone, from all walks of life, is empowered with the knowledge to universally advocate for an environmentally and socially equitable world where we can all enjoy the places we live, work, and come together in our communities.”

Participating students: Kelsey Delahunt, Jeremias Emestica, Khushali Jain, Tyler Haas, Yuxin Li, Emerald Liang, Shruti Sridhar, Vivian-Weiwei Sun, Angie Widjaja, Maxwell Wolfe, all BArch ’24