Over the last 15 years, Iranian-born polymath Hamid Rahmanian has created popup books, large-scale cinematic shadow-plays, and concert experiences, telling the story of the Shahnameh, an epic poem that is a foundational touchstone for Persian culture. With the recent publication of The Art & Story of Song of the North and The Seven Trials of Rostam (Kingorama), and the US tour of Song of the North, Prattfolio speaks to Rahmanian about his multimodal approach to artmaking and what continues to motivate his yearslong work with the Shahnameh.

What inspired you to write and create these books adapting the Shahnameh?

Hamid Rahmanian: The Shahnameh is similar to the Iliad and the Odyssey, but it is much longer. In fact, it is the longest poem written by a single poet. This is a book that kept the Persian language alive. The ex-Roman territories like North Africa, Egypt, Libya, and Syria all changed the language to Arabic after a seven-centuries conquest by Muslim Arabs. But this book kept the Persian culture alive and kept us true to who we were, and who we could be in the future.

Fifteen years ago, I used to make movies, animations, fiction, and many different kinds of graphic design. I felt there was a lack of information, and an abundance of misinformation, about my culture in America. I thought it would be beneficial to society to create a body of work that goes around the Shahnameh Epic of Persian Kings, to create a positive outlook and a focus on the literature or visual culture that is hardly ever being promoted to the masses.

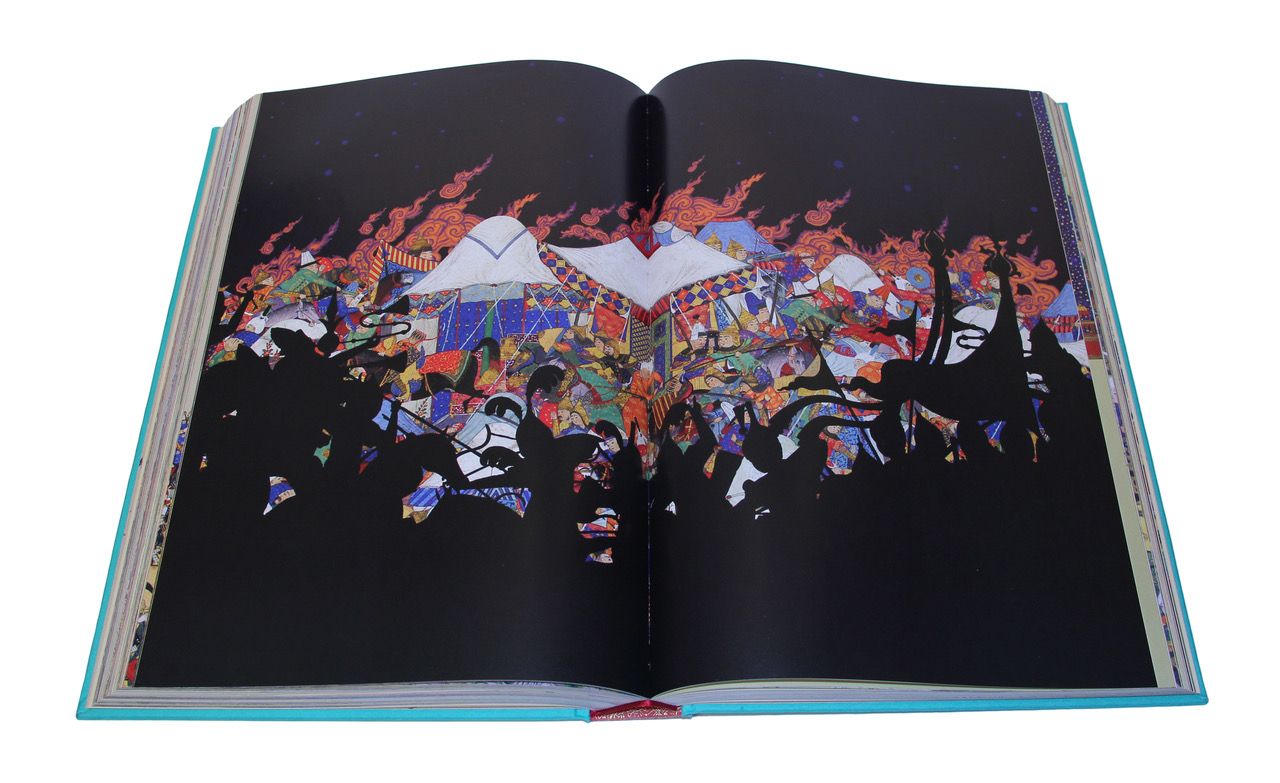

First, I started creating the illustrated edition, which is a 600-page new translation. I commissioned a translator, Ahmad Sadri, to create an accessible, easy, comprehensive translation of the epic and mythological part of the Shahnameh. And then I illustrated almost every page to make it inviting to young and old readers.

The way I illustrated it is really interesting because I didn’t want to sit down as an illustrator and draw everything. We have a tradition of painting and illustrating that has hardly ever been introduced in the Western world, so I put together a collection of over 8,000 pieces of miniatures and lithographs from the late 14th century to the mid-19th century. Anything influenced by Persian painting from Mughal India to all the territories of the Ottoman Empire. Those pieces became the ingredients for illustrating all these plots from this epic poem.

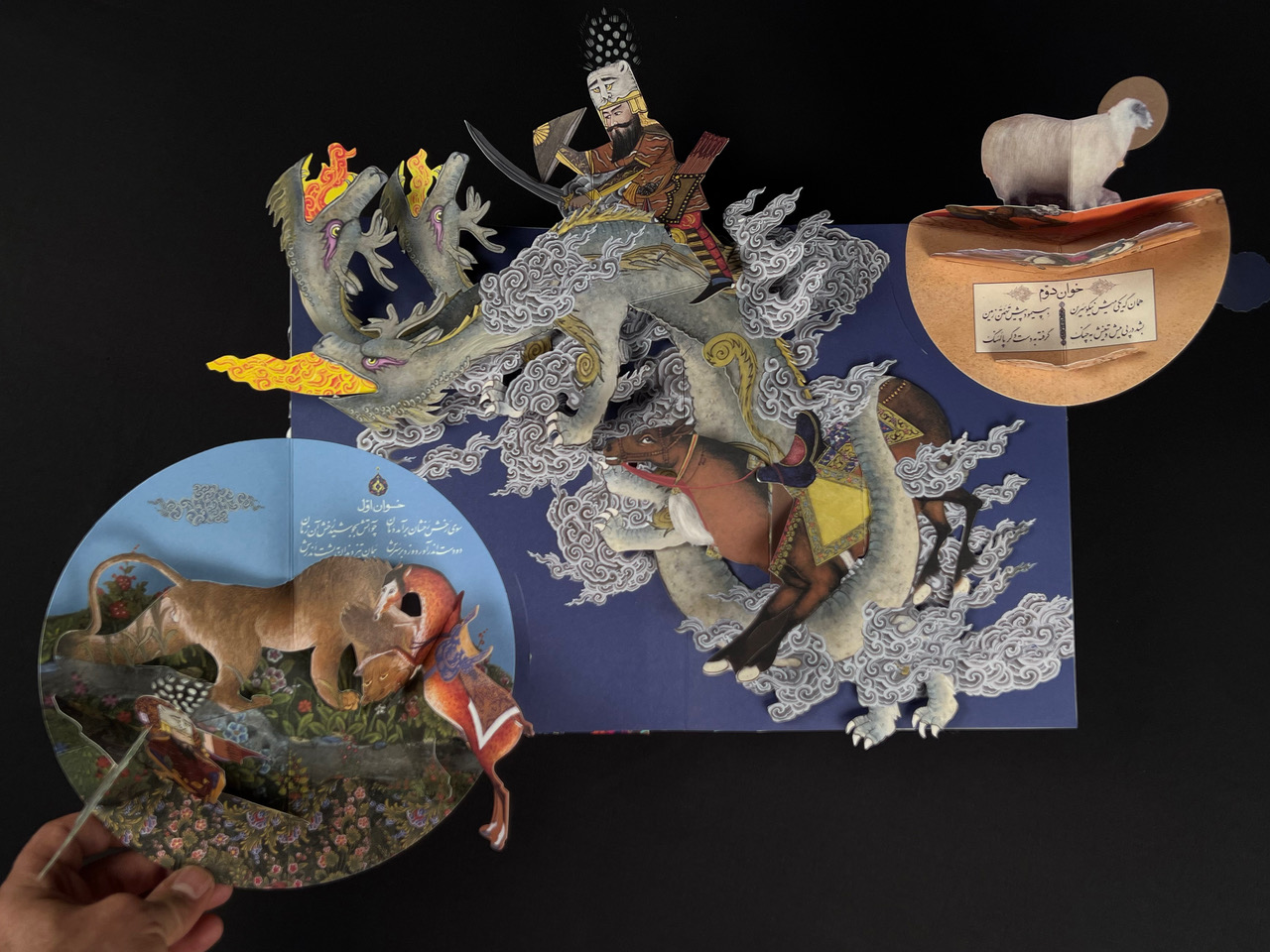

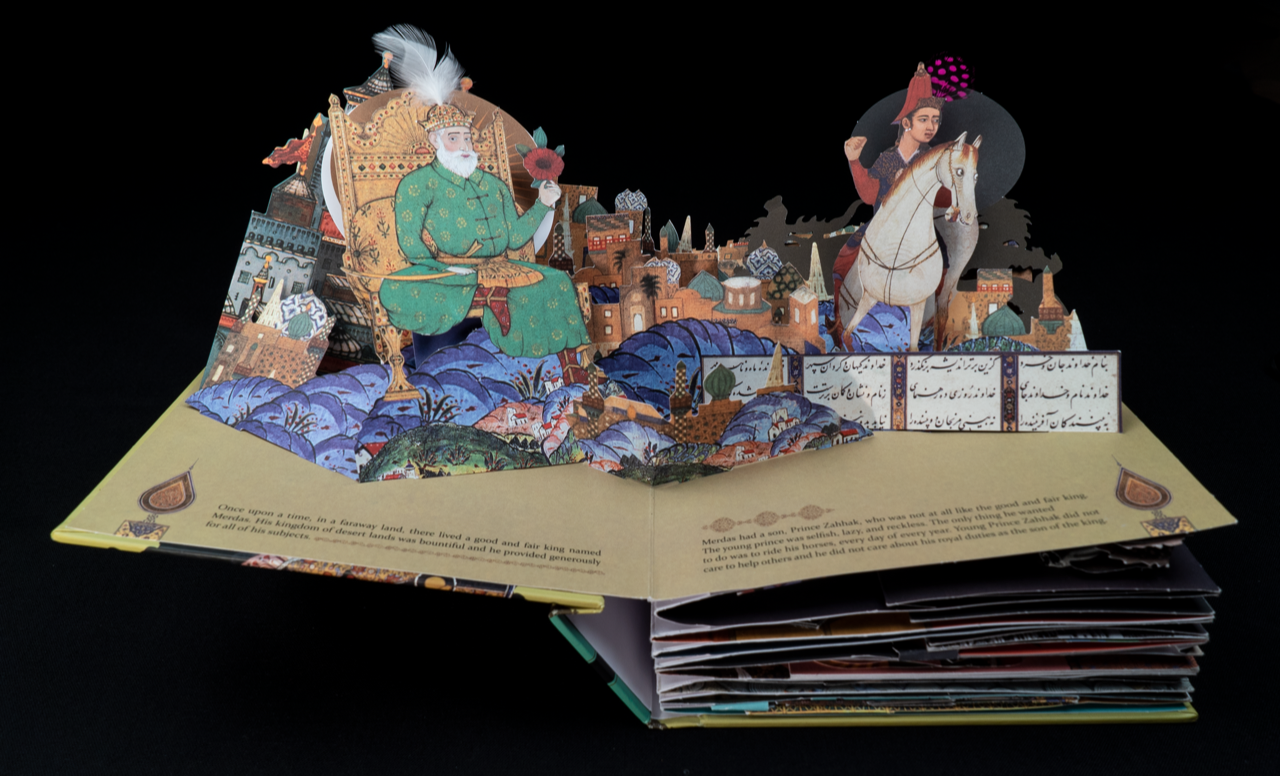

From that process, which took me more than 10,000 hours over the course of four years, came my first book [Shahnameh: The Epic of the Persian Kings], which is in its ninth printing now. That became the foundation of all my projects that have come out since 2013. I did two pop-up books [The Seven Trials of Rostam and Zahhak: The Legend of the Serpent King] with a paper engineer, Simon Arizpe [BFA Communications Design ’06, visiting instructor in communications design], which reflected the same kind of visual traditions. And then I did three shadow theater productions. One of the last ones was Song of the North, which has around 500 puppets.

Can you talk about your multidisciplinary approach to your artmaking?

HR: I’ve not bound myself to one profession. I studied computer animation at Pratt. Before that, I studied graphic design. After graduating from Pratt, I worked for Disney. And then I started making movies.

I have collected skills from all of these experiences and have used them to make different projects. My play Song of the North spent three years in production in New York City. I picked stories [from the Shahnameh] that can stand alone. Sometimes you can not pick one story because you have to know what’s happening before, like an episode from a series, but there are a few exceptions.

So I picked those stories and I adapted them to become more familiar and more accessible to 21st-century audiences. Then, I started building character puppets, designing the faces, and how they should look according to the traditions.

Usually when people also ask me “What do you do?” I always answer, “Depends on the week, the month!” Sometimes I’m a director, sometimes I’m a book illustrator, sometimes I’m a book publisher, and sometimes I’m a book distributor. Some days I paint. I don’t bind myself to one profession.

How did your time at Pratt impact your creative work, especially these projects?

HR: When I was at Pratt, the world was a different place. I remember the third year we had this Silicon Graphics Octane computer that had one gig of RAM. One gig! Imagine that! And we were all fighting over that one-gig computer.

Before that, we were the generation of floppy disks and the zip drive. And I have to say, it was very tough and very slow. I was very ambitious. I think to this day, I am the record holder of the longest animation thesis project ever created. In 1996 I created a six-minute-long animation, for which I received the College Television Award [from the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Foundation]. And I was nominated in the Student Category of the Academy Awards. The competition took place at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival, where Nick Park, the director of Wallace and Gromit, debuted a short stop-motion animation.

In 1996, I got hired by Disney, right after Pratt, after I did that animation, and I worked for Disney for a few years. Then I left and came back to New York and started making documentaries and fiction films until 2009 when I started working on the Shahnameh project, which I thought would be more beneficial for society, and would be more fulfilling for me as an artist, creating something that adds color to the fabric of society and benefits others, not just myself.

What is a challenge you’ve overcome that’s made you a better creator?

HR: In America, anything that comes up around Iran has to go through the prism of politics. Being an immigrant from the “enemy” culture, it is very hard to find your place. The fact I could actually manage to do it for the last 15, 16 years is not short of a miracle.

My driving force is to promote a highly sophisticated art from a culture that has been demonized for such a long time. I’m not creating art for the sake of creating art, my emotions, or my intellect. I have a responsibility to promote the beauty of my culture as best as possible.

For kids around the US, I am planting a seed, something beautiful, meaningful, and sophisticated in their minds about Iranian culture. So hopefully when they grow up, if they become statesmen, if they become the governors, congressmen, congresswomen, they have something beautiful in their mind about Persian culture, this culture that has contributed to Western society for millennia without getting proper credit.

Is there a person whose mentorship or influence has transformed or informed your work?

HR: Good question. I am fortunate that I had many great teachers in my life. I am always seeking teachers. I’m the type of person who likes to learn constantly. So in any opportunity where someone can teach me a way that I should look at the world or some technique, I’m a blank canvas.

When I was growing up, I went to Tehran University. I had a lot of good teachers. At Pratt, I had Rick Perry, who’s no longer with us. I also had Michael O’Rourke [professor emeritus in the Department of Digital Arts], who was my teacher and advisor on my thesis animation.

When does the creative process look collaborative?

HR: I did an audiobook production of the entire epic, which is 12 hours of sound design and sound effects. We had 61 voices. And there is a work I did a few years ago with Yo-Yo Ma’s band, Silk Road Ensemble, a philharmonic experience with animation and lighting design.

The theater experience at the beginning can also be solitary, but once you open up your designs and your methods, you have to have people come in. Eventually, you have actors and builders and a whole crew to collaborate with in order to bring your dream onto the stage. I see myself as a gardener, directing the water to the right tree and irrigating the field. All these kinds of people come and actually make your dream and your vision into a reality. Through them you translate yourself into actual objects, it is like alchemy!

I got help from a Pratt graduate for Song of the North; she helped me animate some of the backgrounds. Her name is Hoda Ramy [MFA Digital Arts ’21]. And the paper engineer I collaborated with on both of the books, Simon Arizpe, teaches at Pratt. Before the pandemic, I got help from the Digital Arts Department and Peter Patchen [then chair of the department] to cut a lot of our puppets. It was the first time I had a studio with a lot of light. Unfortunately, that ended when the pandemic started and I had to transfer them all into my little dark studio!

I did like to work with them and to be at a Pratt facility because it feels like a good space for creativity, and it’s fun and inspiring to have all these people from Pratt involved.

And all that work’s been for this yearslong project.

HR: Yes. It’s been 15 years on the Shahnameh, this single book. And I have another 15 years on it planned.