A graduate of Pratt’s Library and Information Science program, Cynthia Tobar bridges her expertise as an archivist and oral historian with her work as an artist-activist, all with the aim of amplifying underrepresented stories—in her words, “stories of community care and power in housing justice, higher education, and labor justice . . . that resist inequality and the economic divide imposed on our communities.”

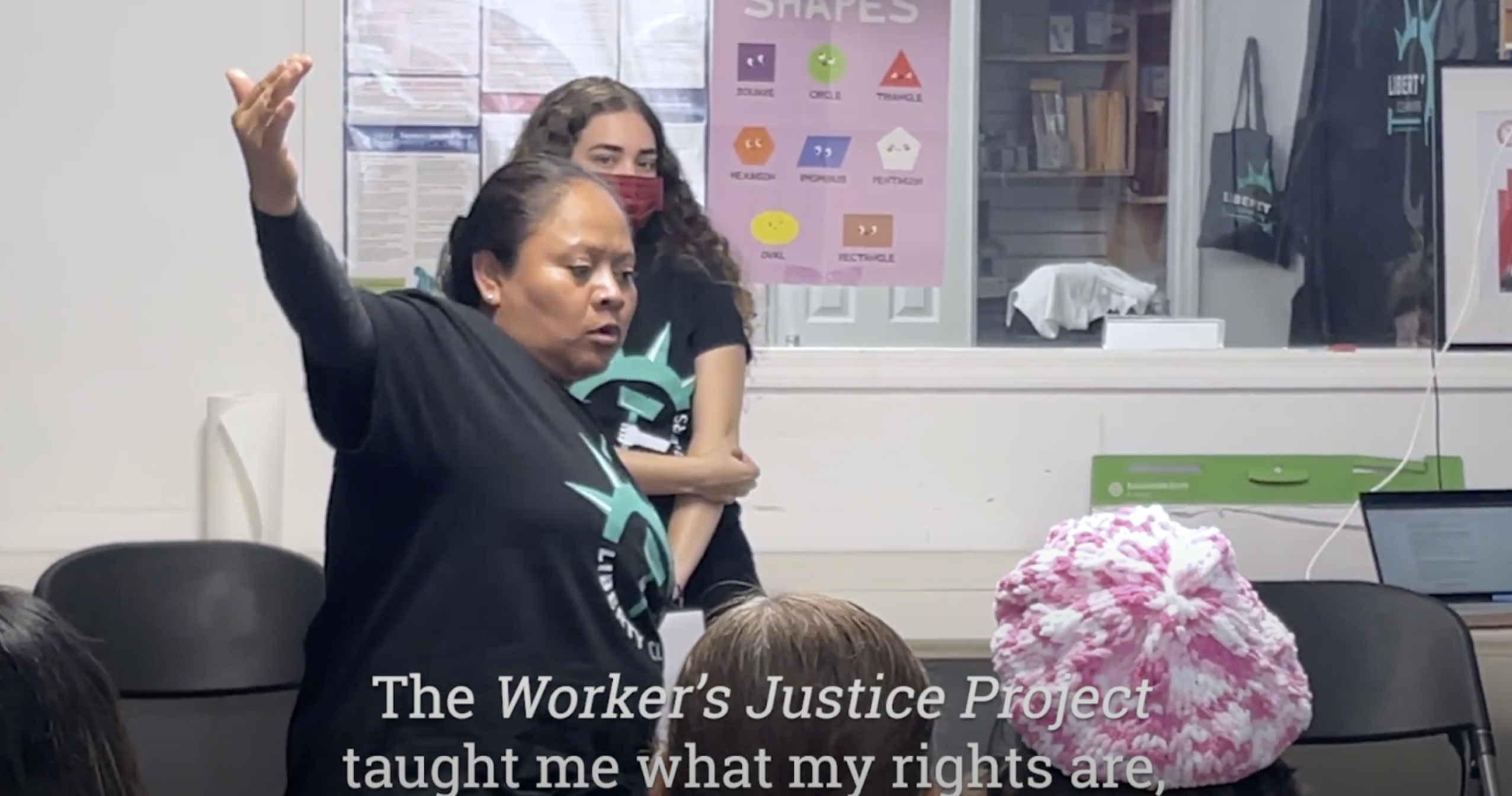

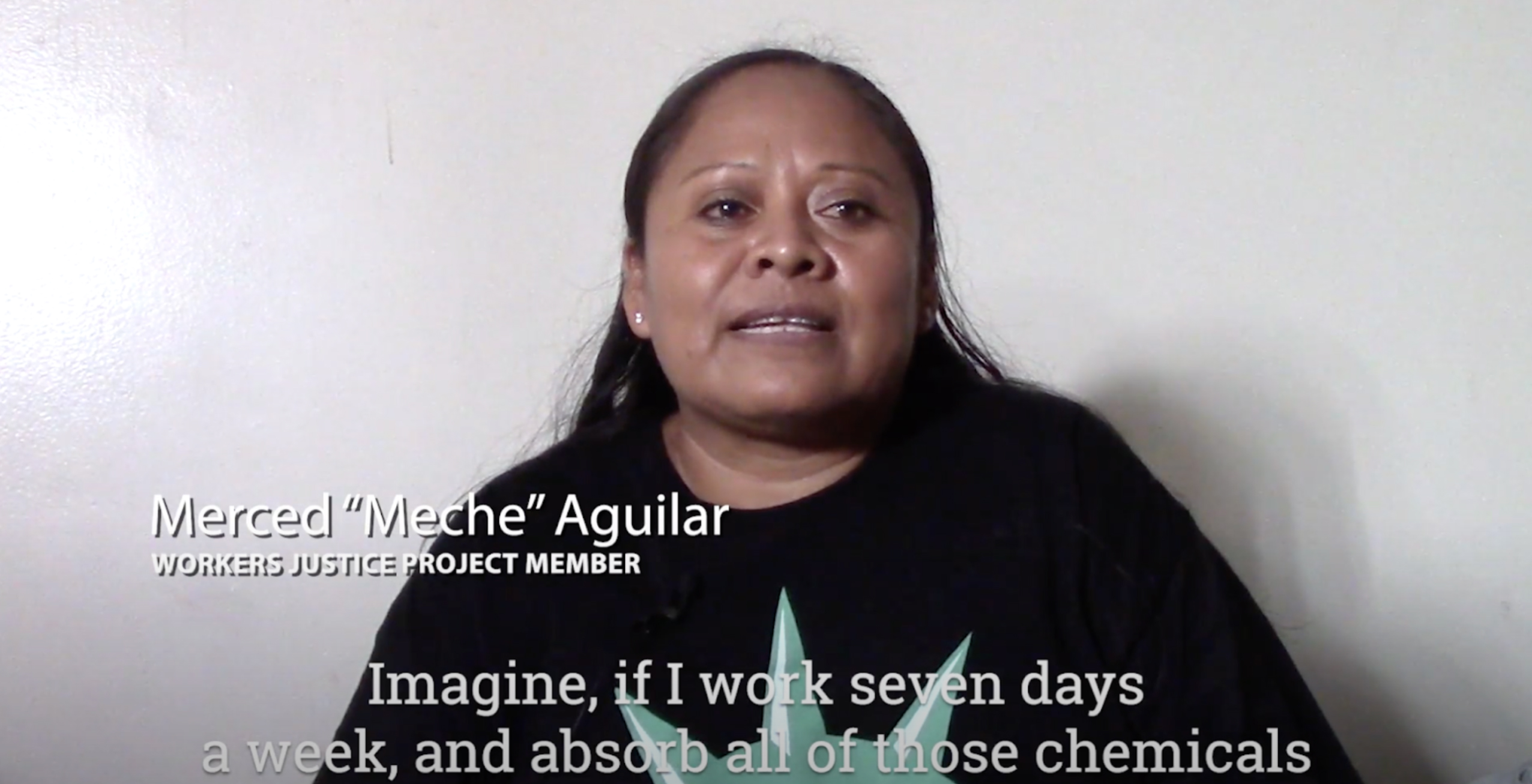

In her recent documentary short film, Mujeres Atrevidas (Bold Women), produced with support from the Pratt Center for Community Development’s Taconic Fellowship program, Tobar presents an intimate glimpse into the professional and personal lives of a group of Brooklyn-based women fighting for better working conditions. As workers in app-based delivery, cleaning, and construction, they come together through their involvement with the Workers Justice Project, a center, founded in 2010, that advocates and organizes for improved workplace conditions and offers educational resources for workers as well as a safe space to build agency and community.

In a Q&A with Prattfolio, Tobar shared background on the film and her oral history practice, and offered advice for emerging artist-activists.

For Mujeres Atrevidas, what drew you to the women of the Workers Justice Project as story subjects/participants?

I was drawn to these women because their stories resonated with my background as a first-generation daughter of Ecuadorian immigrants who also began as low-wage workers in the city.

My mom was a homemaker and my father was a tailor. My father was just barely able to support the family with his salary when we were growing up. Later my mother took on work as a home health aide. The most they ever paid for rent was 800 dollars for a three-bedroom apartment up until their departure from the city in the early aughts. I tell that to people now and they’re just astounded that the city used to be that affordable.

By the time my turn came, I had a child to raise and sustain on my own as a single mother, and that road was pretty turbulent, to say the least. Now, in a city that is getting more expensive by the day, how do you even make ends meet if you’re coming from those circumstances, let alone if you are coming from a single-earner household?

During the pandemic, as delivery workers were suddenly visible and celebrated for the risks they took and the services they performed in the media and the public, large segments of the low-wage, delivery workers were nevertheless left unprotected and excluded from emergency-relief policies.

The subsequent shutdown exposed how dependent many of us had become to living in a digital economy that relies on “invisible labor.” Labor that has everything delivered to our door, and there’s less and less space being provided for people from different walks of life to engage with one another.

As these spaces of engagement decrease, the sense of economic and social isolation for this group increases. And the public is further disconnected from the injustices that this workforce is experiencing.

After observing female-identified workers in this community being underrepresented in media narratives during this time, I wondered how this group was dealing with this disturbing trend.

Coincidentally, I also began to notice the growing intensity of the Workers Justice Project’s campaign work to increase awareness of these issues online, and their fight for a living standard wage for these workers by allying with [the labor group] Los Deliveristas.

When you look at the current salary ranges, they’re not sustainable. They laid bare the growing inequality that’s imposed a heavy toll on their constituency of working poor, people of color, women, immigrants, and others who were marginalized long before the pandemic exposed the cracks in the economic and social protection systems of our country.

It was also inspiring to see all this activity take shape at a women-led worker center!

It was with this mindset that I wanted to do justice for each of these women by providing a space for them to speak about the challenges they face in their work.

I am so grateful to the Pratt Center for their support of this work! Thanks to this funding, I set out to engage with the community within Workers Justice Project, Brooklyn-based worker center that educates, organizes, and fights for better work conditions and social justice in the workplace. I was able to establish a working relationship with them and interview several of their members.

The more I sat with them, the more I realized that I also had to focus on the friendships, sense of community, and empowerment these women identify as their sources of strength in their organizing. Essentially, these women are the heroes of their own lives.

What story were you hoping to tell, and what did you discover along the way? What themes did you focus on in your conversations with the women you interviewed?

I wanted the film to reflect the reality of today’s Brooklyn for low-income, immigrant female workers. While I wanted to question and deconstruct how worker challenges were being dealt with locally—workplace challenges such as harassment, worker safety, and wage theft, I also wanted to ask which aspects of this type of gig work the women found appealing.

What compelled them to seek out this type of work? The resulting stories dispel the myths surrounding the women who regularly take on this work as only coming from uneducated backgrounds.

For instance, one of the workers featured in the film, Ernesta, was trained as a licensed nurse back in Mexico. However, since she was the head of her household and had to quickly provide for her children in a foreign country with limited resources, she decided to pursue food delivery with its low barrier to entry. This work allowed her to set her own working schedule and gave her a relative amount of autonomy, since she works as an independent contractor.

Many women gravitate to this type of work primarily because of its flexibility, which is a big incentive for working mothers since the job allows them to accommodate their hours to their children’s school schedules. This allows them ample time with their children in order to oversee their homework and prepare dinners for their families.

Curiously, these are aspects that many professional women in the workforce do not often encounter in their fields, and this was one of the more illuminating findings I surfaced from the interviews. My film scope soon expanded to not only feature the stories of female Deliveristas, but also capture the narratives of domestic cleaners to document their effort to form their own union collective as Liberty Cleaners.

The conversations also focused on uncovering the tactics that Workers Justice Project staff applied to help these women build power to win economic and workplace gains—from educating domestic cleaners on how to concoct their own detergents without the harmful chemicals they often find in store bought cleaning products, to providing English-language courses.

I was moved to see how labor justice manifests in spaces such as the Workers Justice Project. This organization strives to provide these marginalized female workers with opportunities to learn and advocate for themselves in safe spaces, giving them the room to address difficult issues that matter to them, which result in transformative strategies.

This is a promising model that can enhance continuing learning and organizing to advance worker-informed labor policy solutions. My hope is that this will paint a more representative picture of these women’s impact on the labor movement in Brooklyn.

“I wanted to be part of a documentation and archival process that was non-elitist, transparent, and accessible to the community.”

What made documentary film an ideal medium for bringing light to this story?

I wanted to amplify my oral history practice via documentary film. Up until then, I conducted video oral histories and directed short film vignettes.

Documentary filmmaking, which I view as an extension of my oral history practice, allows me to broaden public awareness of this topic as well as the impact Workers Justice Project’s advocacy has on these workers’ empowerment. The documentary genre helped me to widely spread the urgency of these women’s experiences and their perspectives as low-wage workers and offer this compelling vision for an equitable future to a wider audience.

My goal with Mujeres Atrevidas is to provides viewers with a look at this growing contemporary social movement, interweaving the stories of female workers with depictions of how worker centers and their members come to understand the need not only to contest economic power through policy and organizing, but that in order to win, political and cultural power is critical.

What do you hope viewers will take away from the film?

My hope is that audiences will get an insightful look at what daily conditions female frontline workers face while illuminating the key role workers centers can have in cities and states across the country, especially at this critical moment in our country’s history as new labor policies and standards, such as domestic workers’ bills of rights and higher minimum wages, are being enacted.

At a time when trade unions and worker organizations are re-emerging in the public eye, worker centers provide a range of services, social and cultural spaces, and support for marginalized communities who don’t have the same level of access to the resources that existing trade unions provide.

These member-driven centers emphasize place-based organizing rather than work-site-based actions; leadership development and internal democracy; popular education and coalition building. These characteristics show us the extent of just how such centers can interface with the current actions in the US labor movement.

Ultimately, I hope viewers will empathize and be as moved as I was by how these female workers are able to sustain and improve their lives, despite the daily hurdles that they face, as we collectively reflect on questions regarding this city’s future and its relationship to labor.

How do you see your information and library science/archives background informing your practices as an artist, oral historian, and filmmaker—to name some of the roles you embodied to make Mujeres Atrevidas?

I encountered library and archival work during a crucial turning point in my life, when I was shifting from working as a public school teacher back in my old childhood neighborhood of Jackson Heights in Queens.

While I was ready to move on beyond my experience working in public schools, I wasn’t as ready to give up on the public service, outreach, and community-building aspects that I relished as a teacher. Librarianship proved to be a perfect blend of public service and education, and I found the librarian’s role in facilitating a patron’s sense of agency in knowledge creation—with them coming into library spaces seeking knowledge on their own terms—profoundly liberating.

This new occupation also aligned with my core activist leanings and allowed me to continue work on my own projects that examines and challenges power dynamics in social justice movements, but now from a different angle: the documentarian’s perspective.

While you were a student at Pratt, did you take advantage of any particular resources or opportunities that have helped orient you in your work? Or was there something you learned or discovered during your time as a student that shaped your practice in a particular way?

Beginning my studies at Pratt, I was able to plug into a service learning opportunity interning at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, which thrilled me to no end! I remember how much this place meant to me as a broke undergrad years earlier, roaming through their vinyl collection looking for obscure, strange, and fascinating music.

This was the food that nourished me during those dismal times, and I was so giddy to be a part of helping to preserve and increase accessibility to those performing arts materials. And I had never even heard of archiving before that point and was ecstatic to see that I could sustain myself, and actually get paid for this work! Not that it was a huge amount of money, but I was delighted to work there and my fate as an archivist was sealed.

It was while working there and taking archives coursework at Pratt that I was introduced to oral history as a documentary practice, and I began to delve deeper in my newfound calling. I also began to question and use a critical lens to analyze power relationships in archival practice, challenging the traditional nature of archives and the principles underlying their custody and management.

I wanted to be a part of the new social reckoning I was witnessing in the archival field. I was drawn to arguments that questioned how we determine by which guidelines archives are kept, and how we reconsider what items are signaled as being of “historical interest” in archives. By applying community-based and participatory approaches in archiving, I believe archives can center the stories and experiences of communities excluded in dominant narratives of history.

Archives can function as a site of resistance and solidarity. In this sense, I entered the archival field determined to use inclusive archiving as my approach and use oral history as my method. I wanted to be part of a documentation and archival process that was non-elitist, transparent, and accessible to the community. Oral history does that—it creates a shared space where folks can gather, learn and thrive—just by listening.

“You’d be surprised what is possible if you experiment and open yourself up to the various approaches you can take as you work your way to making sense of the world.”

Where does this documentary project sit within the larger span of your research and practice?

My art practice and research places a great deal of power back to those most underrepresented in our society, and provides an alternative interpretation to the public. I explore different ways of presenting history as it is unfolding. I extend this further with my oral history and documentary practice by amplifying stories of community care and power in housing justice, higher education and labor justice. Documentaries are a powerful vehicle for presenting these counter-stories that resist increasing inequality and the economic divide imposed on our communities to viewers.

For people in the early stages of building or evolving their careers, like students at Pratt, who are looking to develop practices that bridge art making, activism, and scholarship, what advice would you offer? What has guided you professionally as you’ve carved a multifaceted path for your career?

My advice, for what it’s worth, is to follow your passion. Mine was being able to take what I learned documenting activist stories of everyday people demonstrating the strength of their convictions and apply this as my “scholarly” focus in my research and artmaking.

Refuse to take a myopic approach toward your particular interests. You’d be surprised what is possible if you experiment and open yourself up to the various approaches you can take as you work your way to making sense of the world. It doesn’t need to be perfect, it just needs to resonate with you.