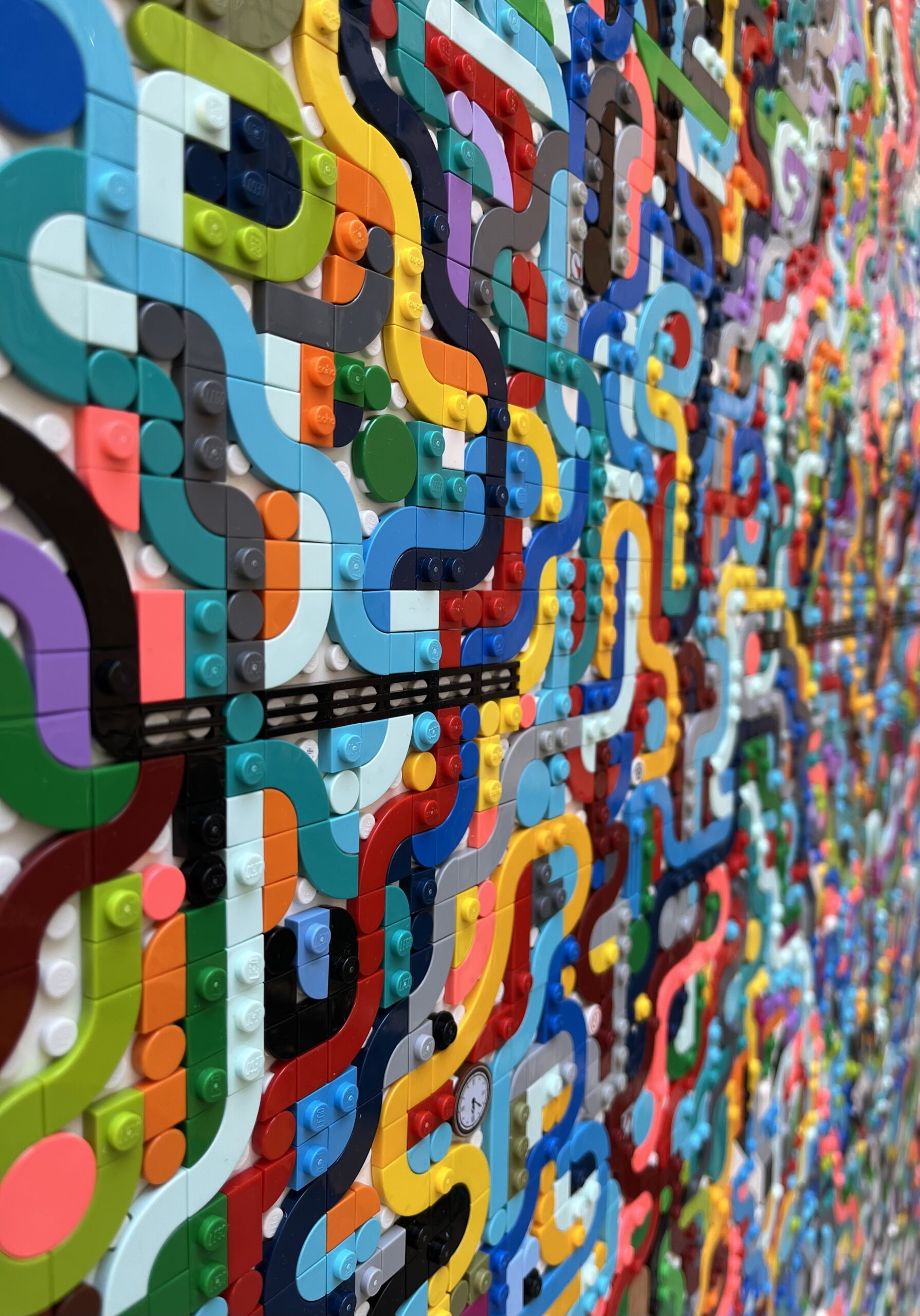

“It is not those differences between us that are separating us. It is rather our refusal to recognize those differences,” read lines of text in one of Jaye Moon’s paintings. The quotation is Audre Lorde’s, and in this work and others by Moon, like Blowin’ in the Wind below, featuring Bob Dylan’s lyrics, the words are set in Braille, rendered in the studs of Lego bricks.

Moon studied fine arts at Pratt in the early 1990s, under Robert Zakarian and John Monti, concentrating on sculpture and earning her MFA in 1994. Since that decade, she has been creating artworks with Lego, translating literary passages, song lyrics, and her own writing to Braille within the paintings, inviting those who encounter them to a tactile and visual experience. Moon came to the process at a time when she was navigating language and belonging after coming to the US from Korea. In Braille, which she taught herself to read and write, and the numerical system of Lego bricks she found a universality as well as aesthetic beauty.

A longtime Brooklyn resident, Moon had her work included earlier this year in The Brooklyn Artists Exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum along with a number of fellow Pratt alumni. In March, she was inducted into the New York Foundation for the Arts Hall of Fame, where she was celebrated for her unique and inclusive approach to art making. In Prattfolio’s career Q&A, Moon shared a window into her practice and persistence in working with unconventional materials.

What’s a daily practice that prepares you for your work?

Each morning, a simple breakfast clears my mind and prepares me to create. Then, I organize my Lego bricks by color and shape—it gives me a sense of control and focus.

What’s a tool you can’t live without?

Lego bricks are essential to my practice. They let me build tactile, Braille-based abstractions that communicate across sight and touch, merging color, language, and accessibility into inclusive visual art.

When you hit a roadblock, what’s your tactic for getting unstuck?

When I hit a roadblock, I pause and step away from the work. I take a walk or shift my attention to something mundane. This helps me gain a fresh perspective and return with renewed clarity.

How do you creatively recharge?

I find creative energy in quiet, everyday moments—readings, slow walks, conversations, and daily rhythms. These simple pauses help me reset, gain unexpected clarity, and reconnect with a deeper sense of balance and awareness in life.

In the ’90s, being told Lego wasn’t “real” art motivated me to go deeper.

What’s the most inspiring place in New York City for you?

The most inspiring place in New York City for me is Brooklyn, my home for over 35 years. Its everyday life and cultural diversity constantly spark new ideas and fuel my artmaking.

How has living in the city influenced your work?

Living in New York City has exposed me to different cultures, identities, and social issues. The city’s complexity deeply shapes my work, inspiring inclusive, tactile art that bridges language, accessibility, and emotion.

Who’s the first artist you connected with?

The first artist I truly connected with was Nam June Paik. His groundbreaking multimedia work inspired me to envision my own path blending technology, culture, and public engagement.

Who or what is a major influence for you today in your work?

Life experiences and current issues deeply influence my work. I believe art should reflect our times. I translate narratives from inspiring films, books, and my personal writings into Braille with Lego—bridging touch and vision.

What’s a chance you’re glad you took?

Faced with the difficulty of getting permission in NYC, I installed Lego public art without approval. Those spontaneous acts sparked unexpected community dialogue and opened up new creative possibilities.

Is there a “failure” that turned into a breakthrough?

In the ’90s, being told Lego wasn’t “real” art motivated me to go deeper—transforming that rejection into a breakthrough that shaped my practice around accessibility and interactivity.

What’s your favorite part of the work you do today?

Creating tactile abstract art that transcends differences—inviting blind individuals, people from diverse cultures and backgrounds, and all age groups to engage with the work through their own personal perspective.

Art comes from uncertainty and change; it’s about expressing your unique voice through the journey of your life.

What’s energizing you right now?

I’m energized by creating quiet, meditative abstract works that translate Korean and English literature into Braille with Lego bricks to tell stories that are not only seen but also felt and imagined. I also make daily number paintings based on Braille number codes.

What’s one book you’d recommend to a fellow artist?

I recommend Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde—a collection of essays and speeches exploring identity, feminism, race, and justice. It offers powerful insights on embracing difference and inspiring social change.

What’s the best advice you’ve received?

Stay true to yourself—and to your vision. Don’t be afraid to explore unconventional paths. Art comes from uncertainty and change; it’s about expressing your unique voice through the journey of your life.

Is there a piece of advice you’re glad you didn’t take?

In the ’90s, many dismissed Lego bricks as unfit for art. But I believed in the concept behind them—their universal language, vibrant colors, and number-based structure. I’m glad I trusted that belief and persisted despite the skepticism.

What’s something you learned at Pratt that you’d want to pass along to a student or early-career artist today?

When you honestly express what you truly believe, beyond trends or opinions, that authenticity connects deeply with others. No matter what the criticism is, if you stand firm in your belief, someone will recognize your true worth. ![]()