In the work of Blake Marques Carrington, artist, associate professor in the Digital Arts Department at Pratt, and coordinator of the department’s Art and Technology program, the distinction between the digital and physical worlds dissolves, creating new ways to experience the interplay of human perception and technology.

This can look like entering a white cube gallery rumbling with the sounds of distant explosions and discovering bass shakers affixed to the ceiling, producing subtle tremors that reverberate like fireworks. Or, it can mean watching as the Beaux-Arts facade of a museum appears to crumble, then reassemble itself—an illusion created through video projection. Visitors to Brooklyn’s Prospect Park might encounter Carrington’s work in the form of two AIs affixed to a tree, battling in a cycle of creation and critique, pruning pixels until they produce an image of a bonsai.

Carrington first dipped his toes into digital media in high school, when a teacher introduced him to Photoshop. With this novel tool, he manipulated images, then painted them. Twenty years later, he’s had four US solo exhibitions, released six music albums under the name Russian Ark Sakura, and collaborated on concert visuals with rock star Patti Smith and the experimental sound art group Soundwalk Collective. The tools he employs today include powerful software like Unreal Engine, widely adopted in the film and gaming industries to create 3D graphics, and TouchDesigner, which allows users to connect blocks of information called “nodes” to generate interactive experiences. Large language learning models, like ChatGPT, serve as brainstorming partners and resources for technical advice. Though Carrington is an adept programmer, it’s often technological limitations–glitches, distortions, and the opaque logic of AI–that yield his most fruitful experiments.

As artists reckon with the ways in which emerging technologies like AI and machine learning are transforming our understanding of creativity, Prattfolio caught up with Carrington to ask about how he’s engaging with these technologies in his practice and in the classroom.

As an artist, how would you characterize your perspective on technology?

I emphasize to my students that technology and new media don’t just mean an iPhone or computers. In some ways, we could consider a burnt stick of charcoal that early humans used to make drawings on cave walls a form of technology. When oil paint was invented in the early Renaissance, that was a form of technology. So, as artists, it’s good for us to keep deep time in mind when thinking about technology and how humans have a special ability to make tools.

A question I like to think about is how tools interact with and shape the human sensorium: our complete perceptual system, including the five senses of seeing, hearing, taste, touch, and smell, as well as other senses, like our sense of our body in space. How are those senses all shaped with technology? How do we shape technology with our senses? The feedback loop between our sensorium and the external world has always fascinated me.

I’m consistently experimenting with and researching new tools, especially related to AI. It’s sometimes hard to carve out time for play that doesn’t need to have a product at the end of it. But when dealing with technology, you need to keep a sense of experimentation.

Based on your experience with AI, what opportunities do you see this technology creating for artists?

The main positive that I’ve seen among my students is that, while we’re all interested in these tools, we don’t think AI is some sort of savior. I’ve had students do work focused on exploring the levels of AI—experimenting with processes where it’s human-centered and AI just helps, versus workflows in which AI is making choices and deciding the goal of a given operation.

As far as brainstorming goes, AI can loosen ideas that might be too rigid. For instance, recently I was preparing a new syllabus about electronic music and sounds. I spent a few days writing out many possible ways to structure the semester. After I felt like I had hit my head against the wall and I couldn’t think of other directions I wanted to take the class, I checked with AI, asking, “Okay, what are some possible modules?”

However, I don’t like to start with AI. I like to fight for myself first, and get to a point where I’m struggling, and then maybe let AI loosen my gears a bit.

Are there any challenges of working with AI or ways in which artists should proceed with caution?

In general, I find I’m not interested in generative images, video, or sounds. The reason is that I’m an artist: I love getting deep in the process and discovering new things. I feel like I’m missing out on the most beautiful part of artmaking if I outsource that brainwork. AI is an average output of everything, right? I don’t think you’re going to get truly unique outputs from a mishmash of everything that’s on the internet.

An ethical critique would certainly be related to copyright and how AI is based on the unauthorized copying of other people’s work. I don’t trust that the big tech companies have our best interests in mind as artists, creators, or humans.

That said, knowing these tools is important. AI is already better than us at certain tasks. It’s going to upend jobs and the economy in general, completely. Eventually, AI is going to do everything better than us, potentially.

Right now, having a strong creative voice, being passionate about what you’re doing, and diving into something extremely deeply is very important. And that’s going to be as good of a security against AI as anything else that I can think of.

Exploring Technology in Works by Blake Marques Carrington

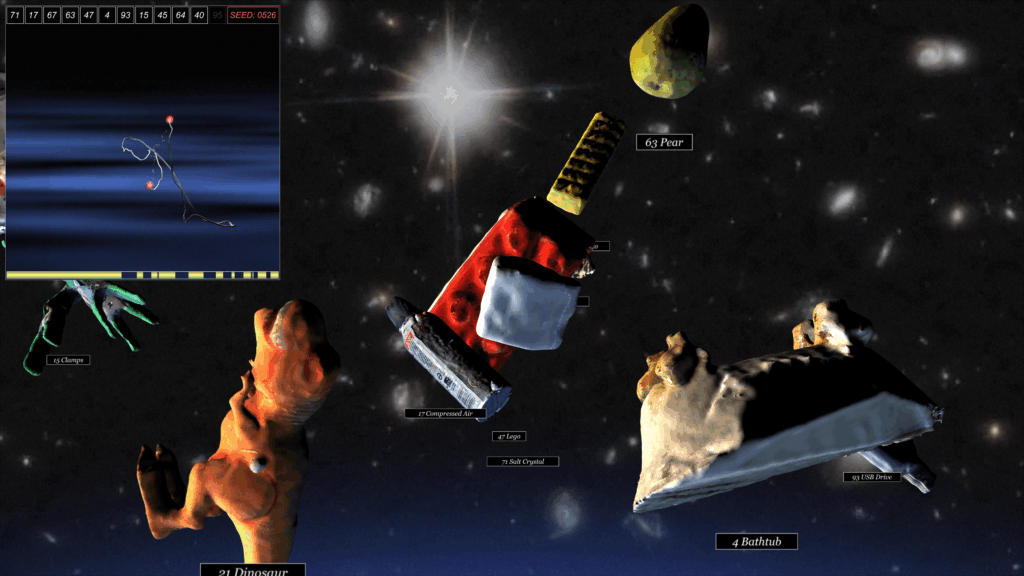

A Mess That Encodes, 2019

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos has argued that humanity will inevitably exhaust Earth’s resources and be forced to colonize space. In this video installation, a distorted plastic dinosaur careens through a version of the cosmos cluttered with knick-knacks. The work critiques utopian fantasies of moving to space to escape the consequences of consumerism and overconsumption.

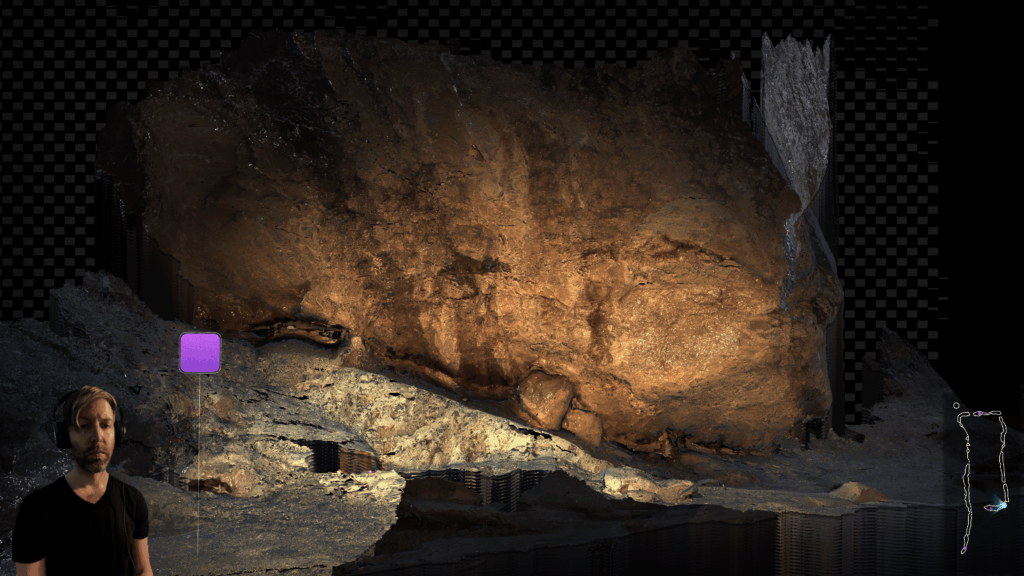

A Model That is Wrong But Useful, 2021

This surreal, apocalyptic wreckage is how a faulty app perceived an ordinary scene of a person resting in a hammock near a trailer. While the app failed at its intended purpose of capturing and modeling the environment, in an artistic context, it is up to the viewer to decide whether the output has any value.

An Infinite Density Over Zero, 2021

In Hollywood blockbusters, a camera can tail a high-octane car chase or take flight with a dragon. Often, these physically impossible maneuvers are achieved with a combination of computer-generated imagery and footage captured with aerial drones. In this interactive installation, players use wireless game controllers to adopt the vantage point of a drone as they navigate an environment created from a digital scan of a Grand Canyon hiking trail—with Carrington appearing on screen as a virtual tour guide during a livestreamed performance based on this work.