“In a lot of what we think of as architecture, we deal with concerns well beyond the building, per se,” says Eunjeong Seong, adjunct associate professor of undergraduate architecture at Pratt. “Buildings are not isolated or singular. There are urban and justice concerns, not to mention climate and energy as well.”

Living through a pandemic could not have made these intertwined concerns more palpable for students in Seong’s advanced studio Micro-Infrastructure and the Epidemiology Clinic, as they considered how architecture might support community care during health crises today and in the future.

Seong wrote the studio from both a technical and empathetic vantage point. It was not hard for the students to share feelings or imagine the user and the human need, but they were also able to step back and focus on the architectural and technical demands. “I imagined this as a way to teach in a pandemic but also to address the human side of architecture being able to imagine its the needs of the user—of people,” Seong remarks.

Seong chose to have students work in the realm of micro-infrastructure to address the sudden, presumably temporary need for clinics in a city, with an eye on potentially widespread reuse, given the numerous outbreaks that happen every year around the world. The solution wouldn’t be a new, multimillion-dollar hospital that falls into disuse like so many Olympic stadiums, nor a structure so minimal as a medical tent that wouldn’t be beneficial in every climate. The rapidly deployable clinic was imagined as a way to deliver urgent medical care to communities with diverse and changing needs.

Among the aims of the studio was to engage both literally and conceptually with technical aspects of an epidemiology clinic, such as airflow and air exchange. Seong saw these as a critical and technical means of protection but she also helped students venture into aspects of air viscosity and flow in art and architectural theory. She used cubism and aspects of chiaroscuro and sfumato to discuss how painting could make air palpable. Students were asked to link these histories to more technical concerns such as air exchange and negative air pressure.

They also considered the subtler signifiers of safety, and more profoundly, care, in a clinical environment, seeking to grasp the social issues embedded in epidemic response. Another major objective was to understand how high-impact infectious diseases have shaped urban history and policy, as well as how the field of medicine has shifted from confronting disease as a subject to more holistically treating a person and their body. The clinic as micro-infrastructure conflated urban and architectural histories, and Seong felt it put a greater emphasis on the person—the user—as the actual focus of the work.

Historian Frank Snowden’s eerily prescient epidemics lectures but also Michel Foucault’s The Birth of the Clinic were required viewing and reading. These critical histories became less academic as the students were living in an evolving version of what they were reading. Students based around the world were also sharing their experiences and learning how each place was distinct.

Also a resource was the real-time data being generated around COVID in New York City, such as maps that revealed medical deserts and concentrations of the disease in relation to residents’ socioeconomic status, underscoring the public health inequities that correlate with poverty. And ultimately, the students’ personal encounters with COVID-19 care and all its attendant anxieties brought a rare layer of lived experience to their projects, informing deeply considered designs.

“We’ve learned through the course of this year how clarity, how professionalism, how an emphasis on protocol and sterility, how clinical seriousness is a form of care,” said guest critic Leah Meisterlin, assistant professor in urban planning at Columbia GSAPP, at the final review. “Transparent information, real science, but also a demonstration of those things is a form of care.”

How could architecture improve upon familiar clinical models, drawing on not only technology but also deep empathy to design a broadly functional clinic that not only provides care but makes people feel cared for?

Mapping Safety

All of the students approached their projects from the rare position of stakeholders—where many briefs require designers to step into an experience outside of their own to take on a client’s problem, the concerns and emotions around the patient experience during this pandemic were deeply felt. But Hannah Kim, BArch ’22, was also privy to the unique vantage point of the medical professional working on the front lines.

As the child of a nurse, who in fact contracted COVID and, with family coordination, was able to prevent the disease from infecting other members of the household—Kim became versed in mapping zones of potential contamination and safety within a home, which translated to a program for the clinical environment.

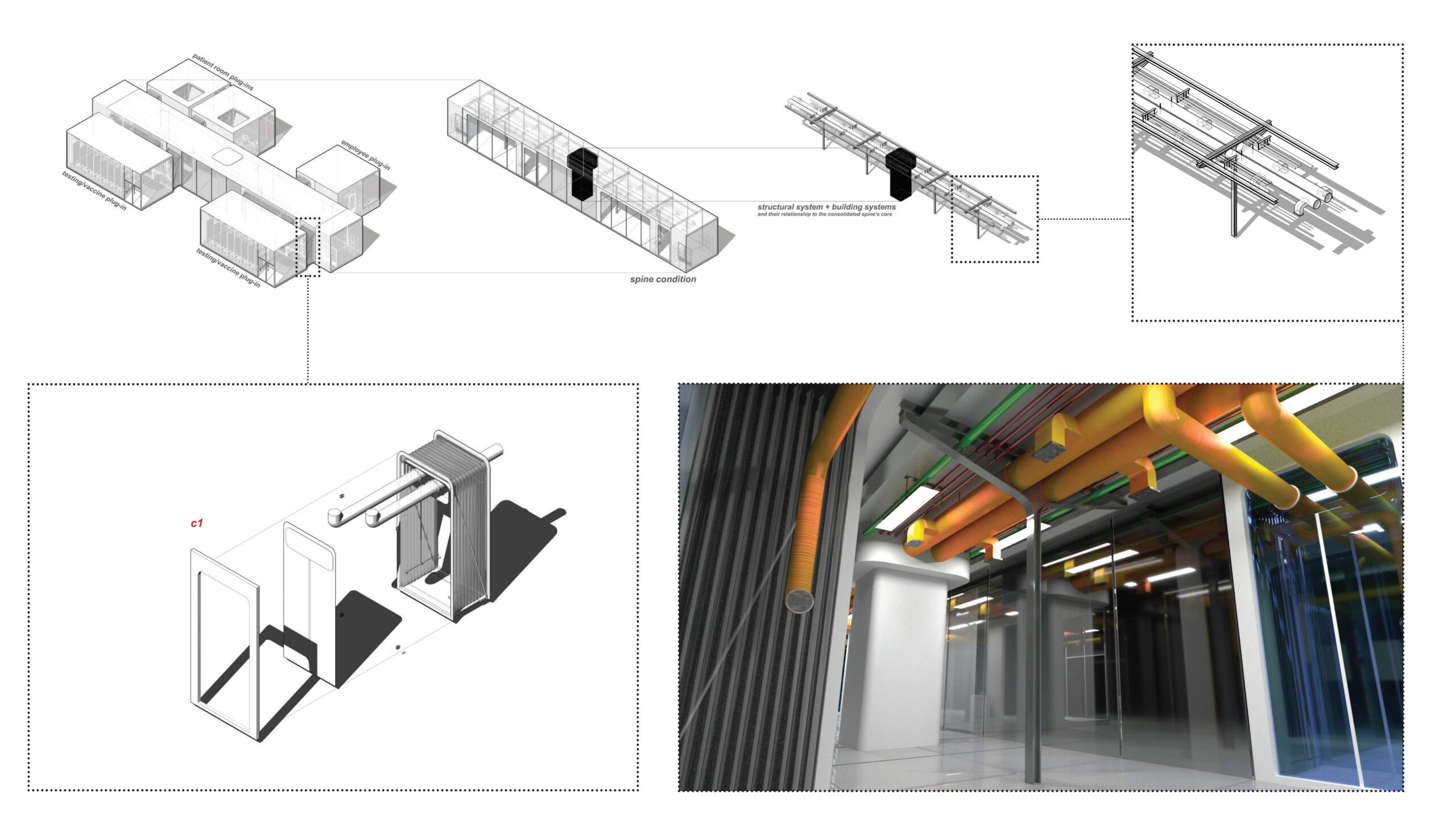

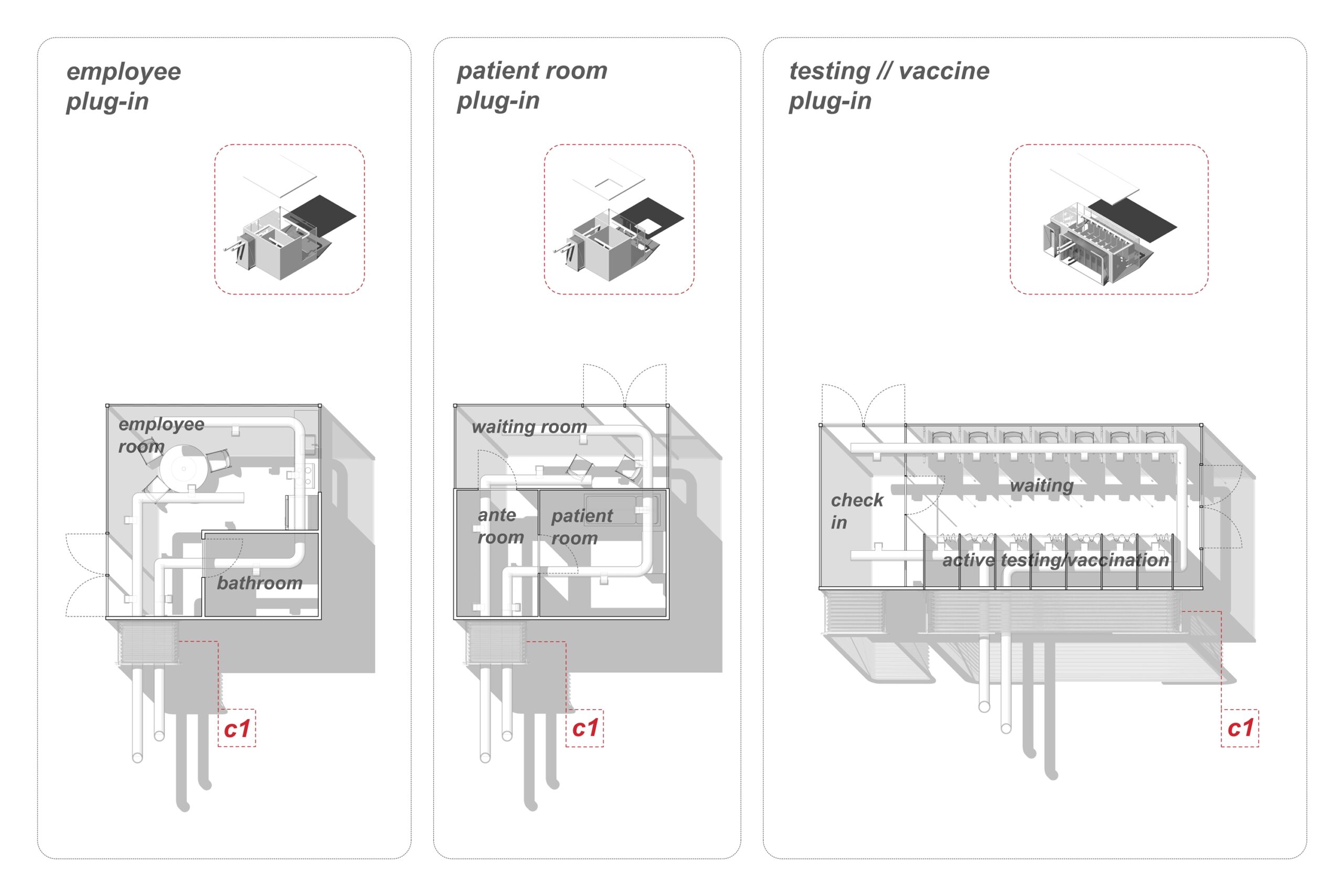

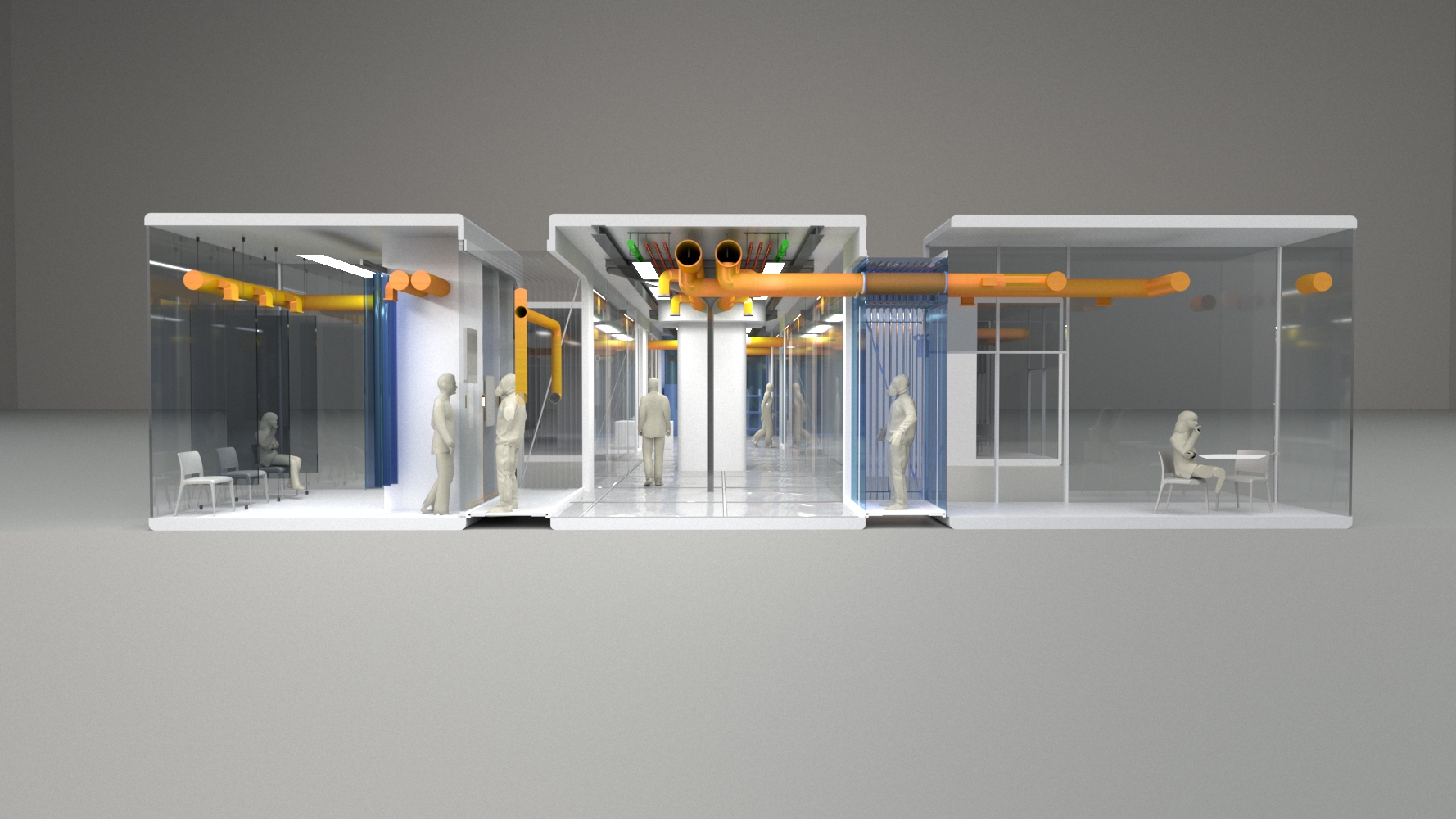

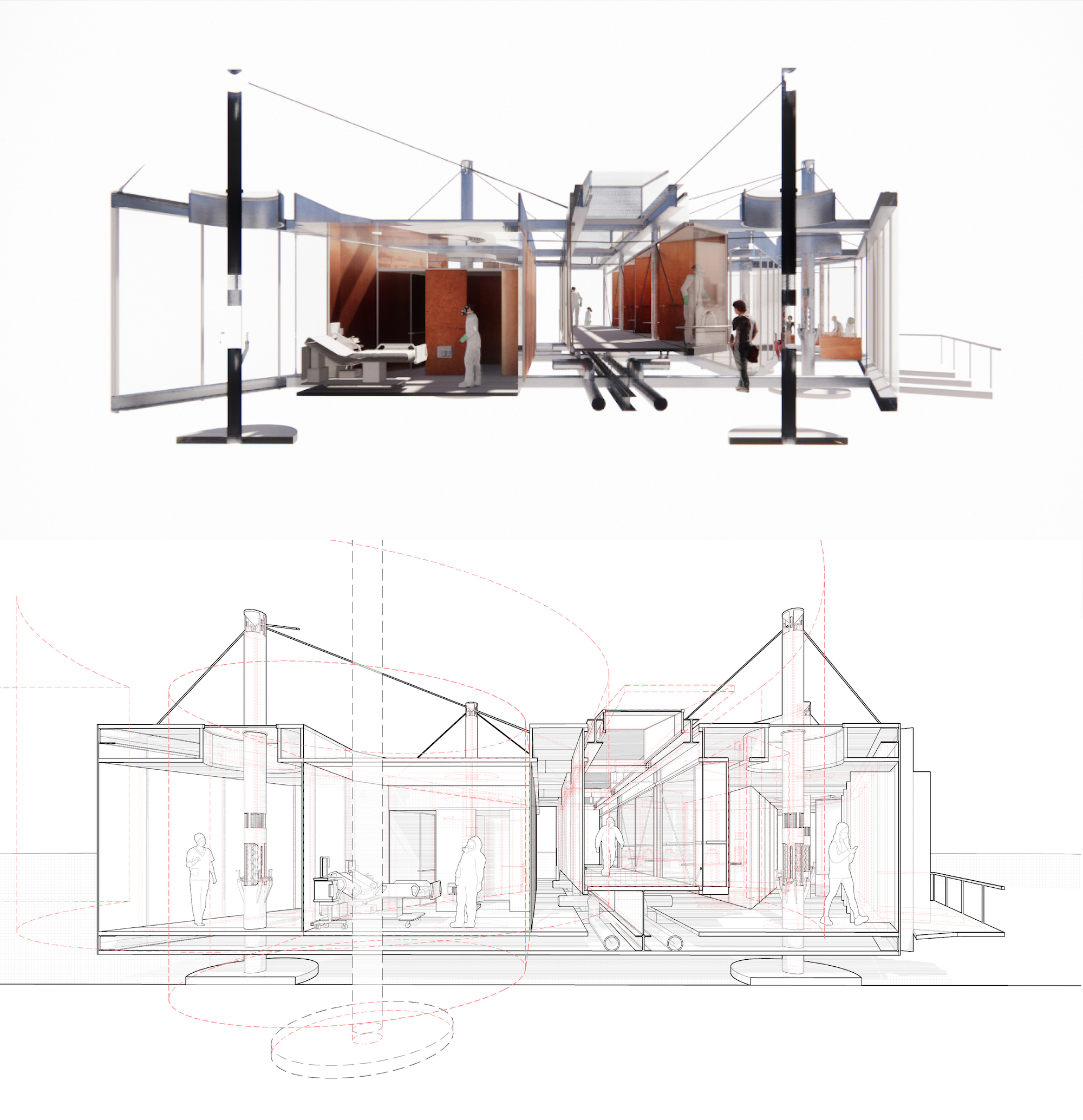

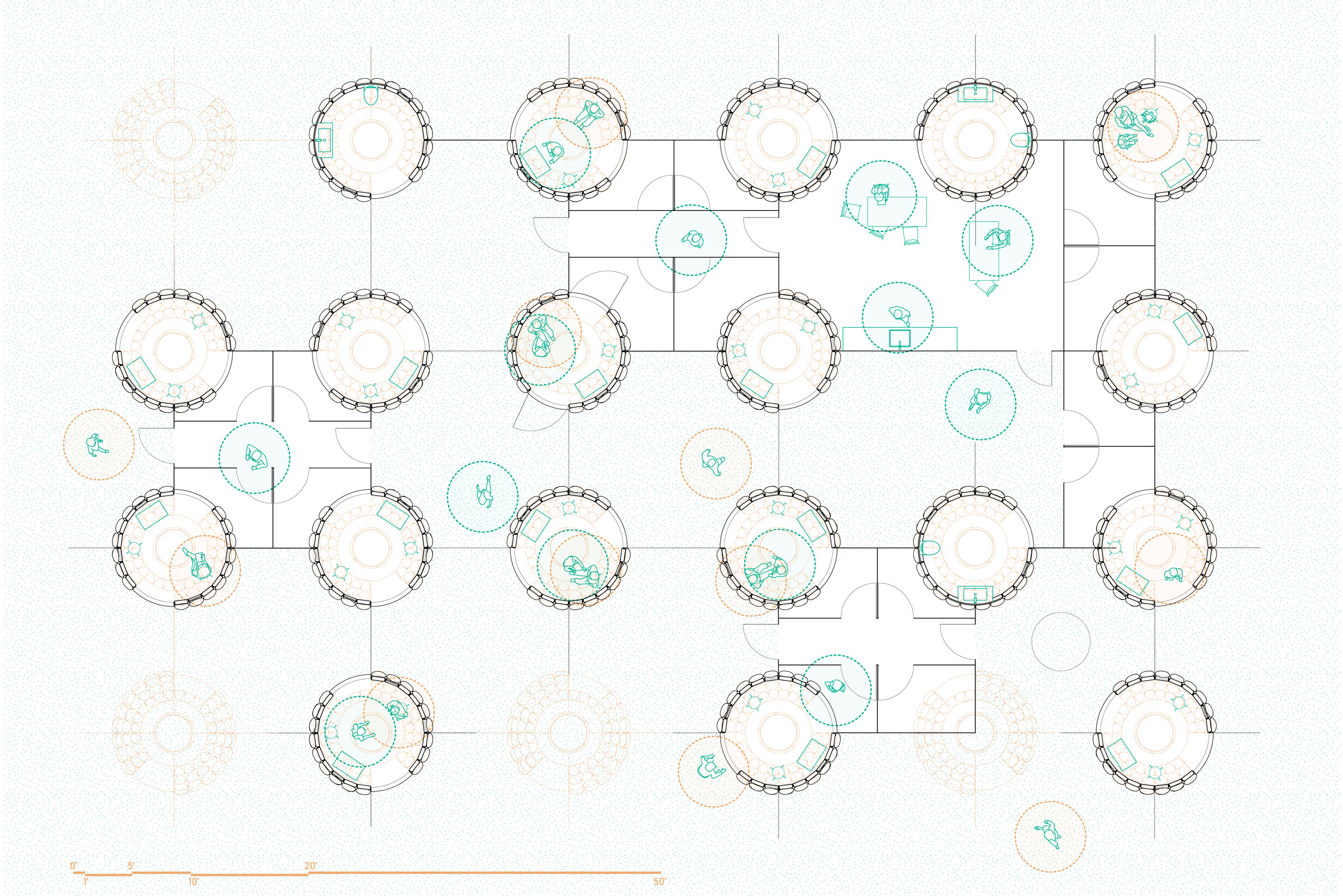

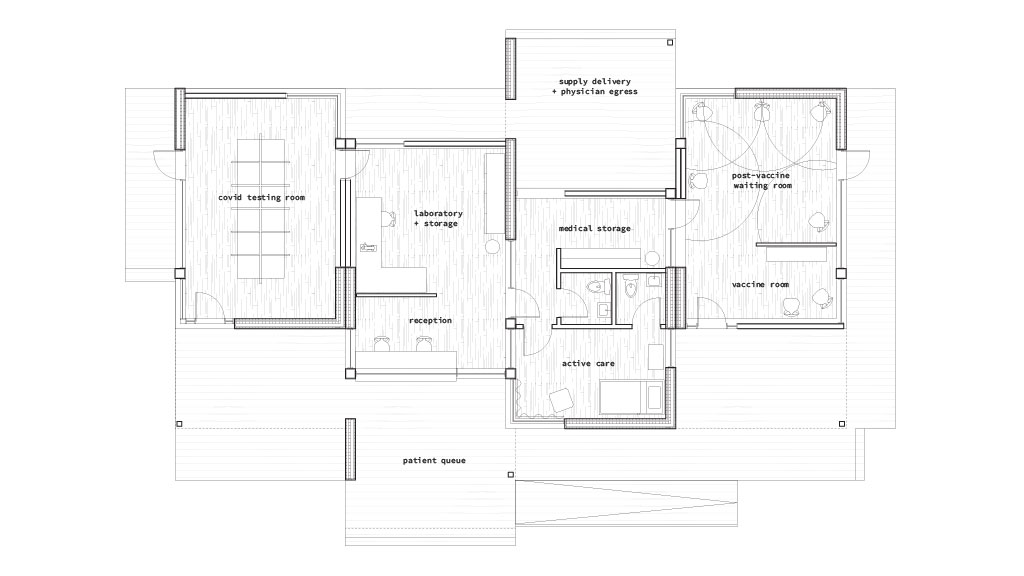

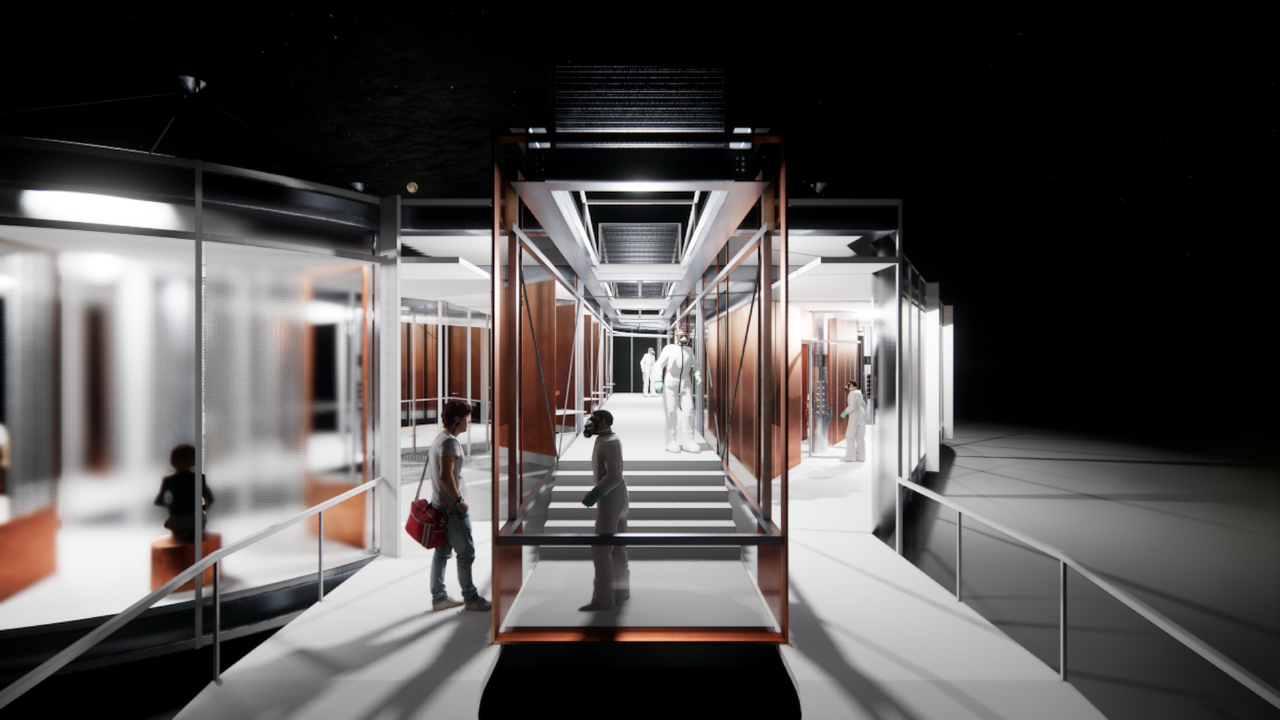

In an approach that prioritizes clarity, a central spine accommodates a series of “plug-ins,” spaces whose use is clearly designated for patients coming in for testing or vaccination, patients who are ill, and employees conducting various forms of clinical work. With features such as exposed pipelines and glass partitions, the proposal, in Kim’s words, “focuses and prioritizes the transparency of information, in the form of architecture and healthcare infrastructure, as an act of care,” to reassure patients and staff alike that they are safe.

An Occupiable Machine

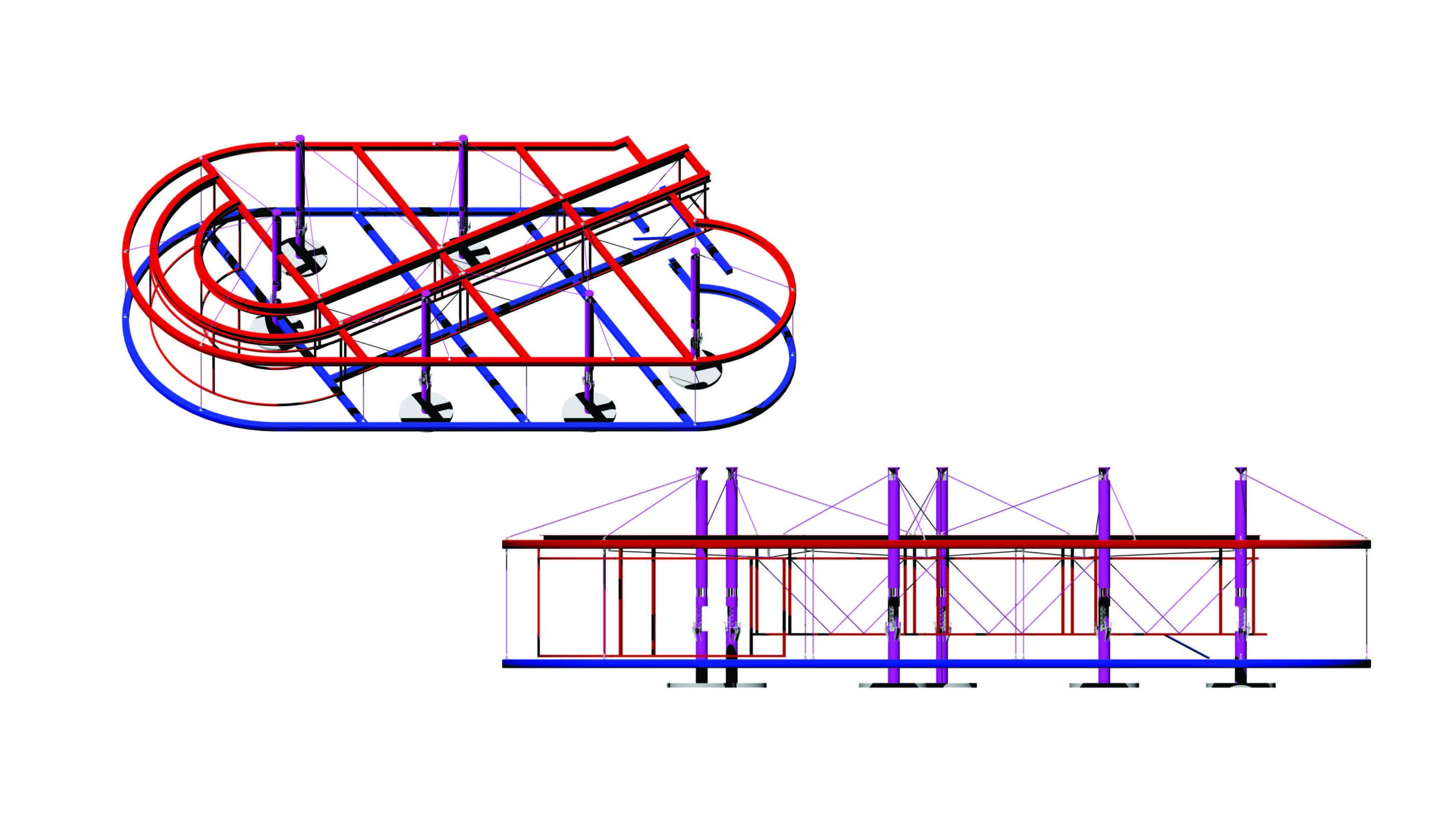

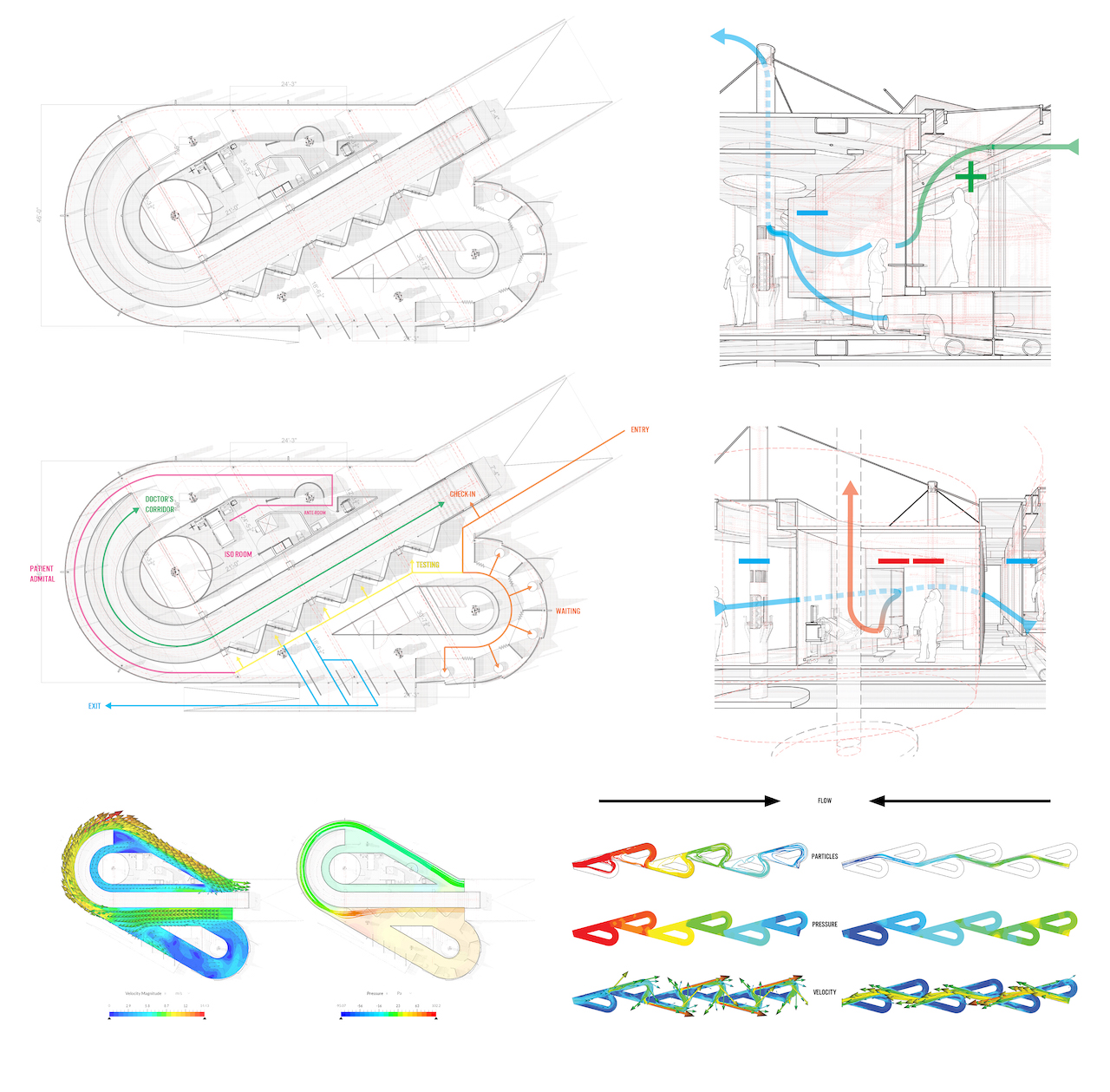

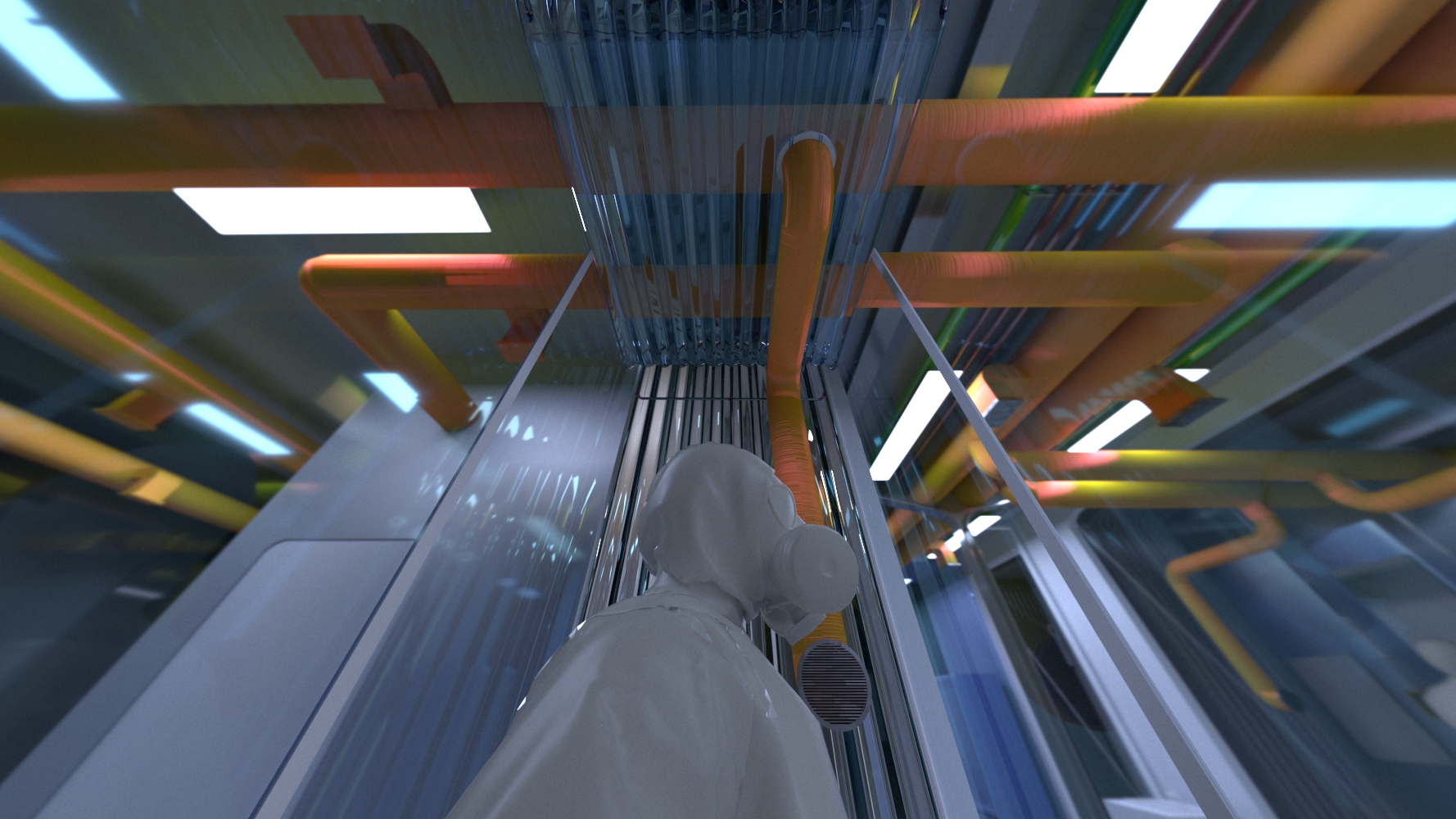

For Emmet Sutton, BArch ’22, the movement of air informed the design of the structure as a whole. It took shape as an “occupiable machine” that, instead of relying on built-in devices to circulate air, uses no mechanical parts.

The structure draws its form from the Tesla valve, which allows air to flow smoothly in only one direction using a system of loops. Sutton created two distinct zones, of positive and negative pressure, with a central spine, or air cavity, where clinicians could safely pivot between their work with sick and healthy patients.

Patients would enter the transparent structure on one side of the spine and wait in a naturally ventilated nook in one of its loops. Divots for testing fall along one corridor of negative pressure, and ill patients would move around another loop, into an isolation room separated from the corridor by an anteroom, to contain and flush contaminated air.

“To occupy the valve or the machine creates a new relationship between the public and the clinic in a pandemic,” Sutton said in the final review presentation. The architecture itself accrues new meaning as a device that protects its inhabitants through invisible means made visible through its specific forms.

An animation by Emmet Sutton highlights the sensory experience of airflow in a clinical environment. Play with sound for the full experience.

The airflow system isn’t the only element that Sutton sought to streamline. Taking into account the variable ground conditions of a potential building site—and, with time at a premium, the need to avoid requiring a foundation—Sutton devised a suspension system. Builders could hoist the structure up on a series of masts, further reducing the tools a team would need to complete the build.

Activating the Air

Taking on the issue of transparency in another form, Rachel Pendleton, BArch ’22, considered how situating a clinic in the truly open air might alleviate patient anxiety. Pendleton drew on personal experiences getting tested for COVID-19—one relatively fast with minimal indoor time, and one with hours of indoor and outdoor waiting time. “It made me very nervous and anxious to share interior space with people for so long, especially with no visualization of airflow,” Pendleton said at the final review.

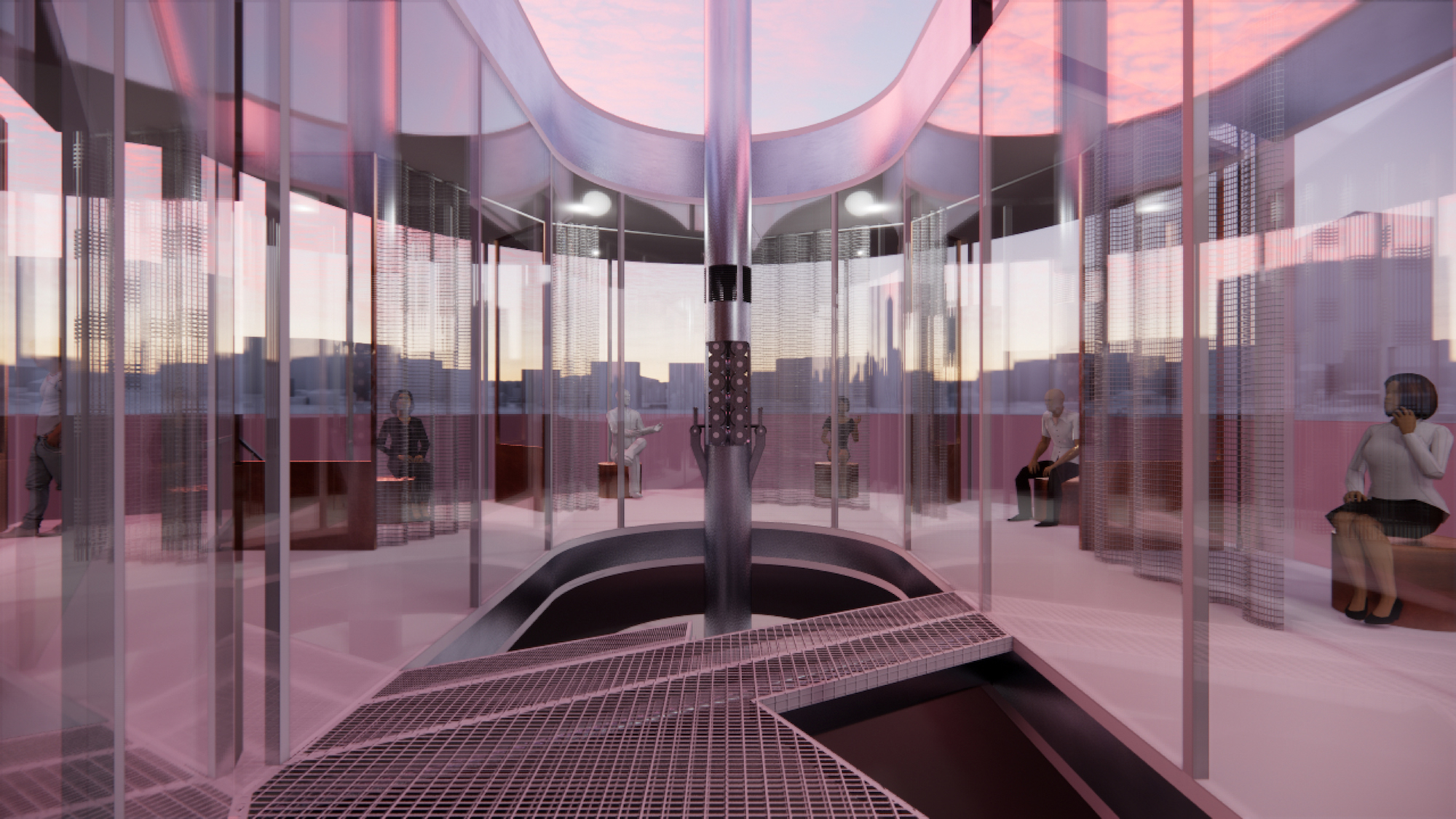

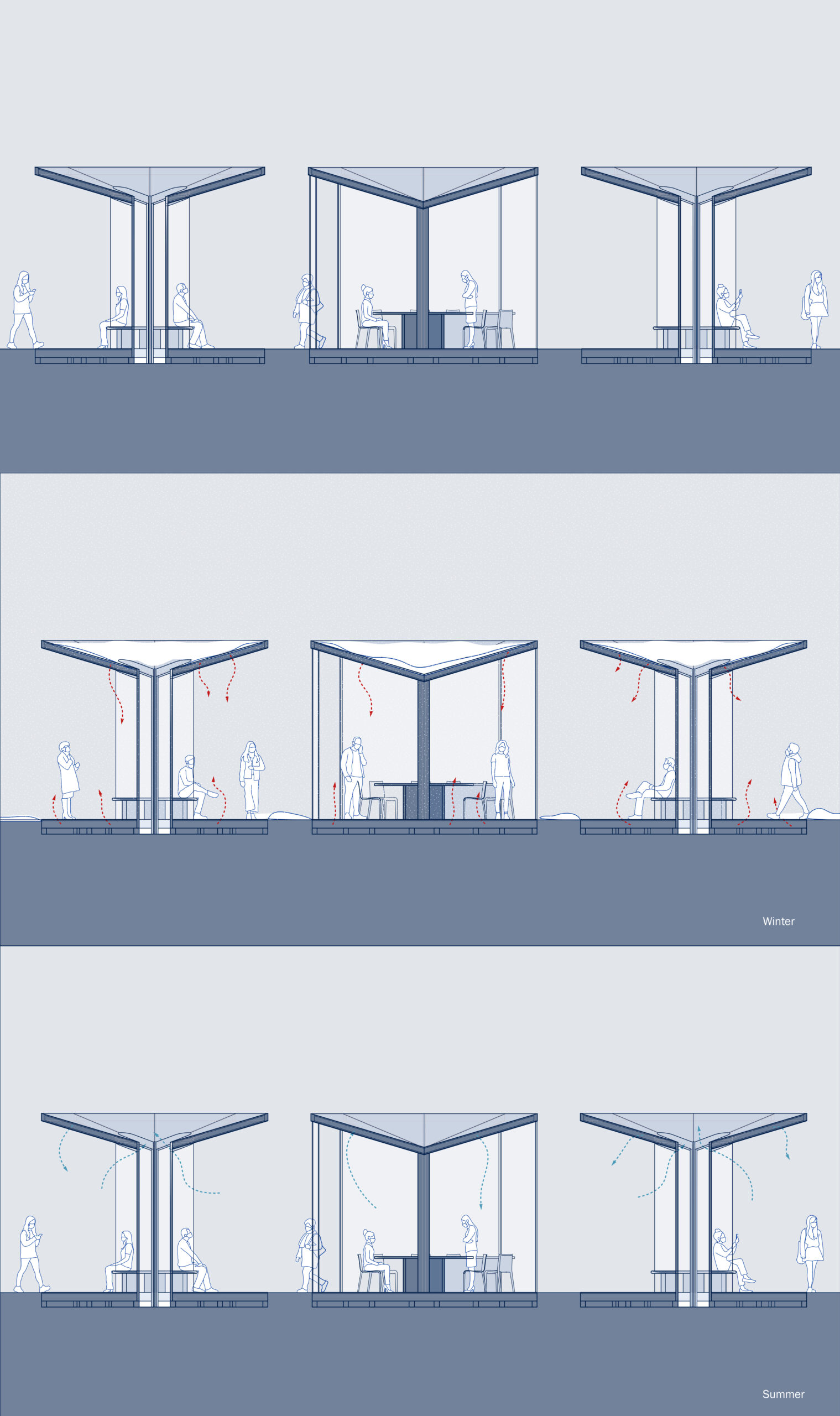

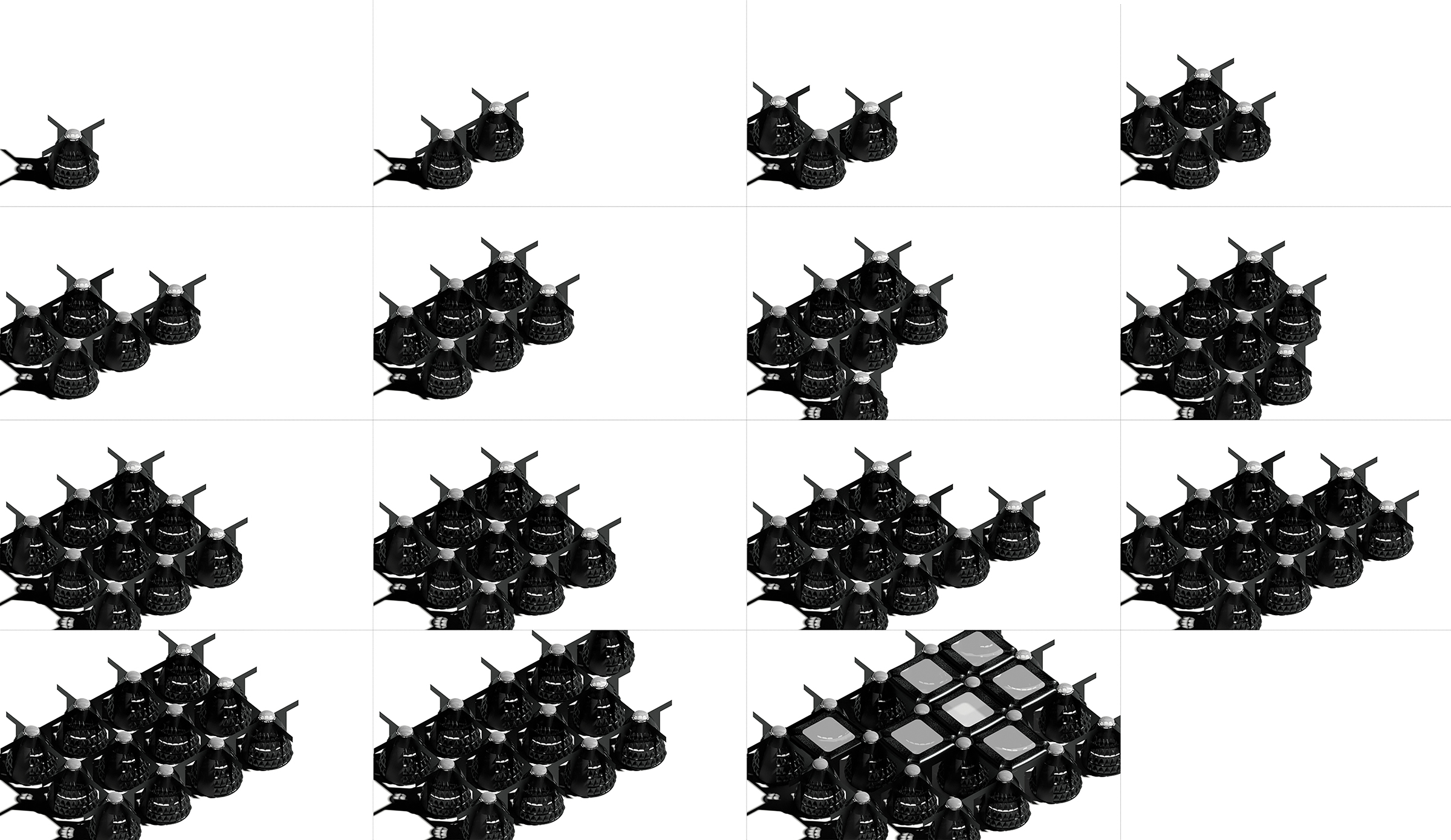

To develop this concept, Pendleton examined airflow in models of different scales—in a MacPro computer and an airplane—and engaged with architectural approaches to pushing, circulating, and holding air. Composed of a series of outdoor pavilions, the clinic proposal reads as a study in how air might hold people, in the tenderest sense.

Where in a region like the American southwest, a totally open structure might be an all-season solution, for more variable climates like New York’s, Pendleton had to think through how to harness warmth for comfort while allowing natural circulation. A glass column anchors each pavilion, with niches around the hub for patients to sit, connecting a canopy and grill flooring (inspired by the MacPro’s cheese-grater-like ventilation panel). Solar panels on the roof power heating coils in the base, creating a zone of warmth and protection without walls.

The clinic’s eye-catching, exposed form would also be a visible symbol of collective response in a health crisis. “Public participation, knowledge, and engagement are crucial contributions to our fight against pandemics,” Pendleton said, “and this clinic would put the process on full display.”

Communicating Security

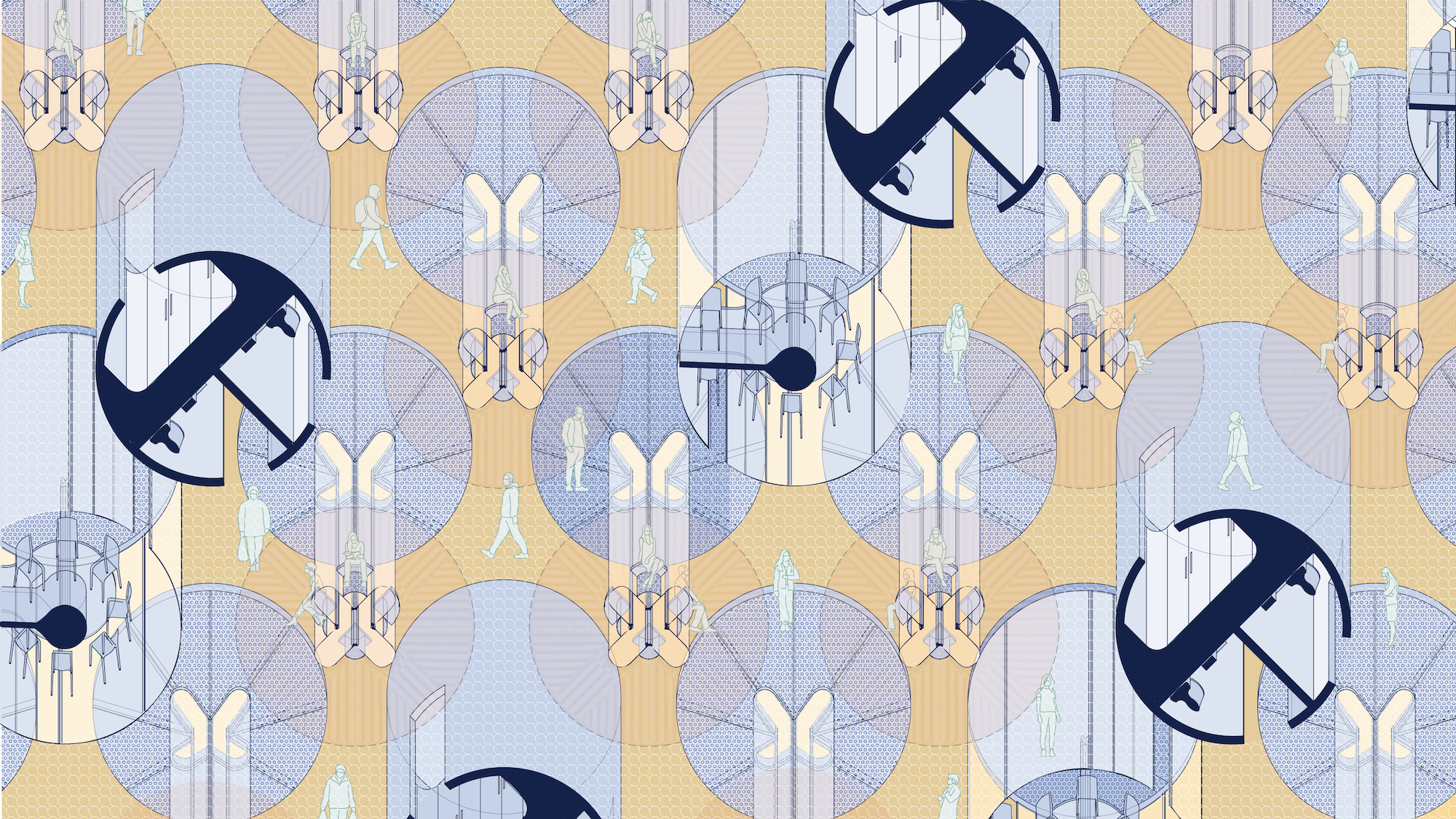

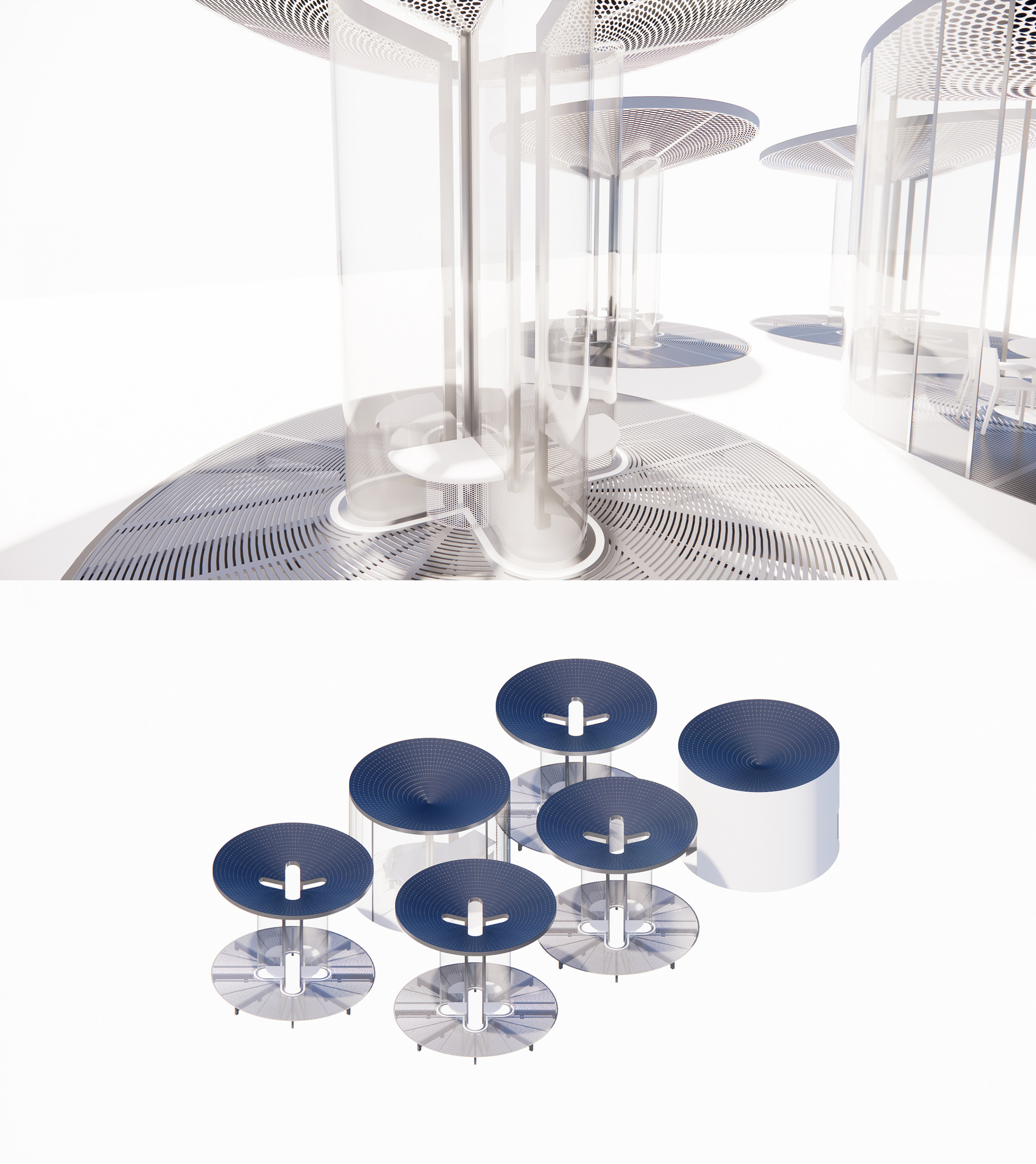

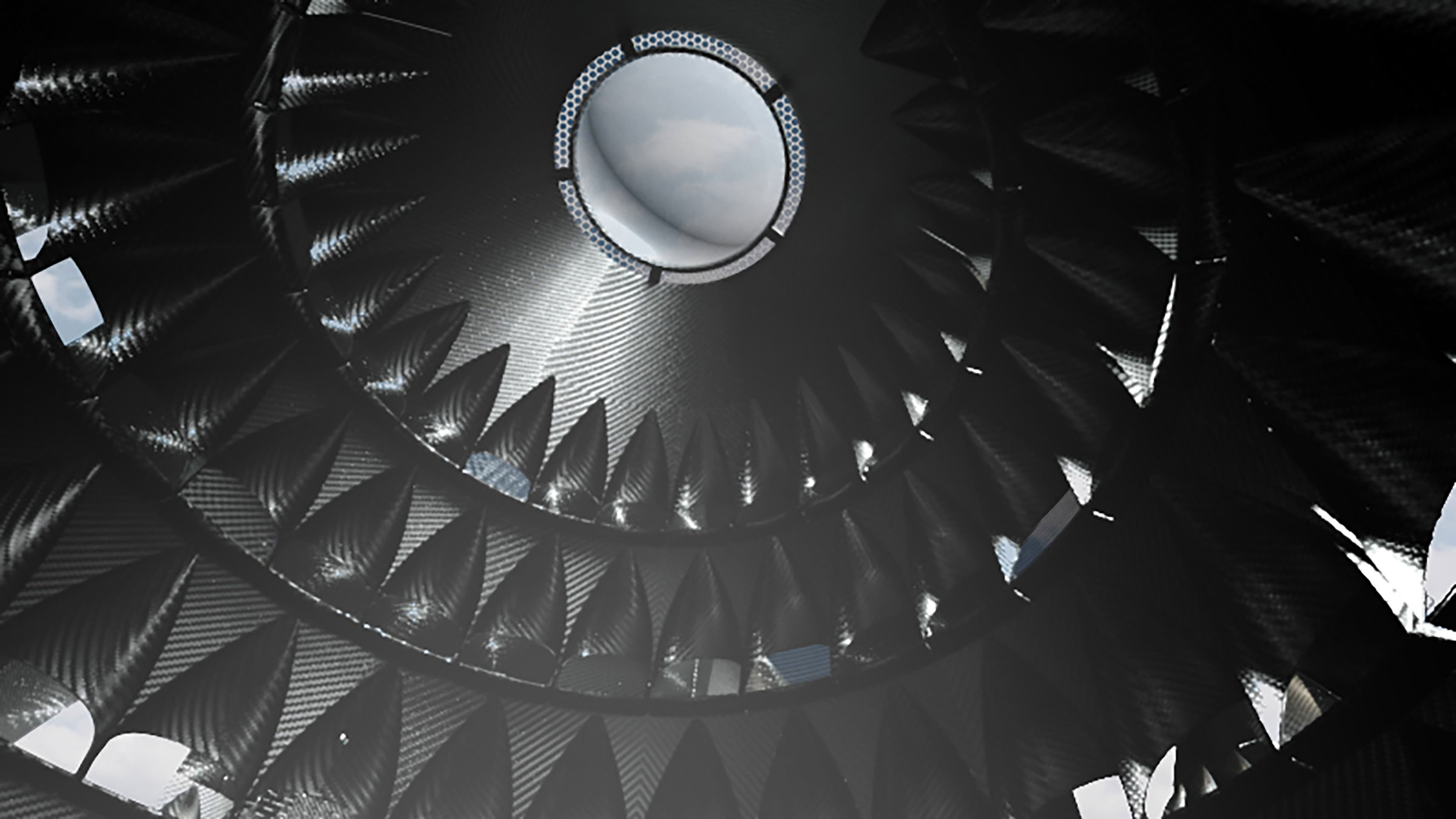

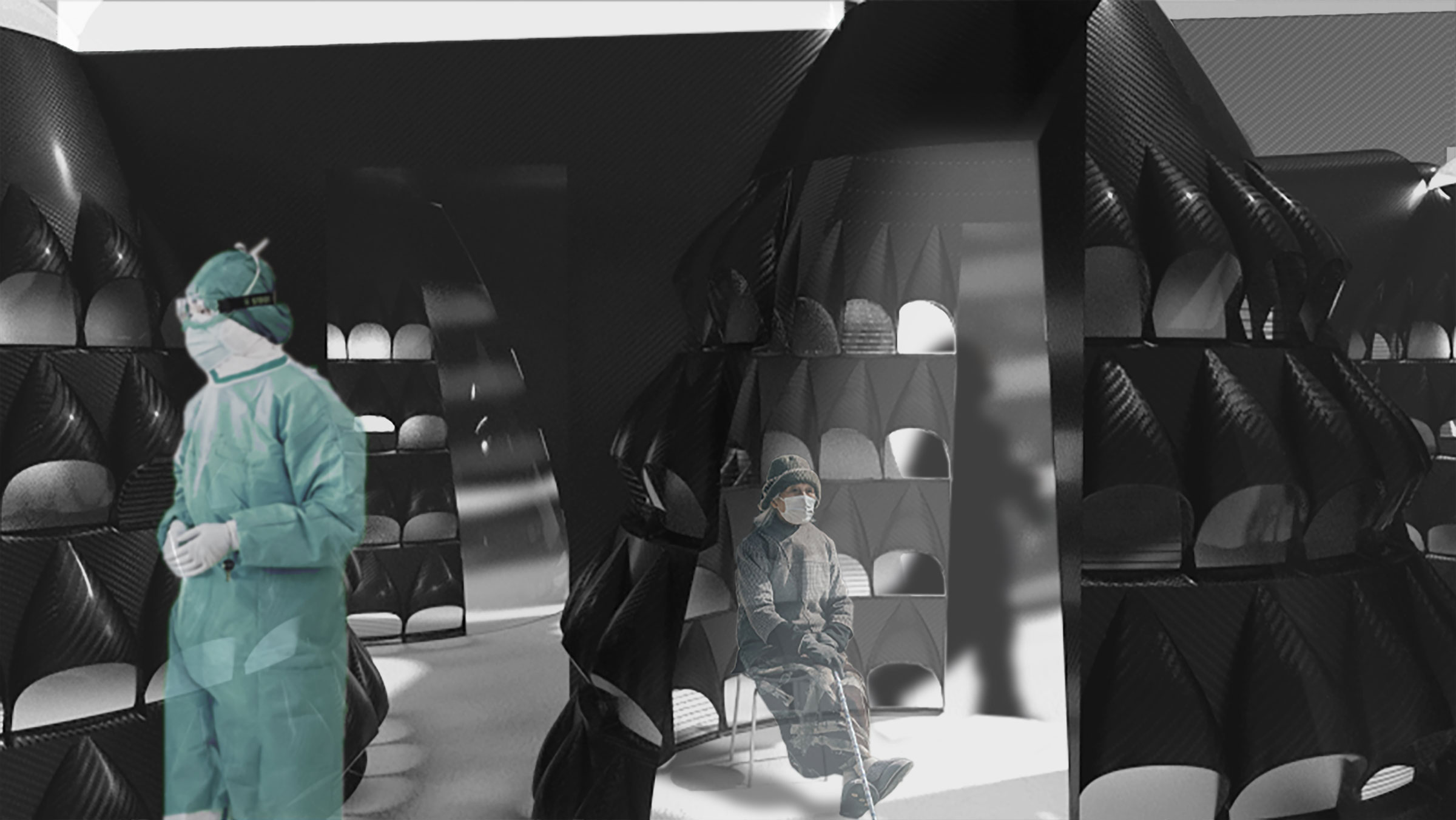

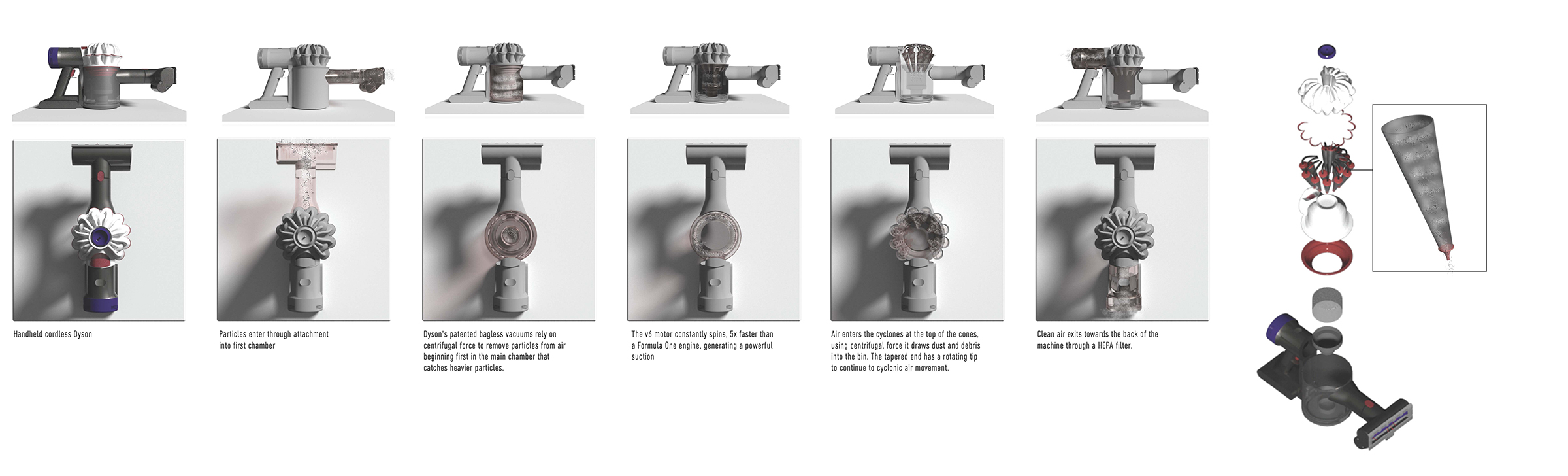

Crystal Griggs, BArch ’22, paid particular attention to two tangible signifiers of safety during the COVID-19 pandemic: physical barriers and ventilation. The result is a system of pods that, in their cocoon-like form, convey protection while also signaling visually that air is moving, through hooded vents in the facade and an exhaust passageway at the top.

Griggs took formal inspiration from the cyclone action of Dyson’s vacuum cleaners, which uses centrifugal force to separate particles and release clean air. The conical pods could stand alone or be connected with open pathways between, with space to make modifications such as the insertion of an anteroom or staff support areas.

For the material, Griggs selected carbon fiber, for its lightweight quality, which would allow a single person to handle each of a pod’s components during construction. There was also an aesthetic consideration—while dark, the material’s reflectivity might invite a play of light that creates a transfixing visual effect for those occupying the space.

“The pods are not only a place for testing that phases into vaccination, but also a place to heal and experience,” Griggs said in the final review presentation. “One can reflect upon the crisis, feel their fear and anxiety, and ultimately reach euphoric tranquility within these temples of solitude.”

Material Comfort

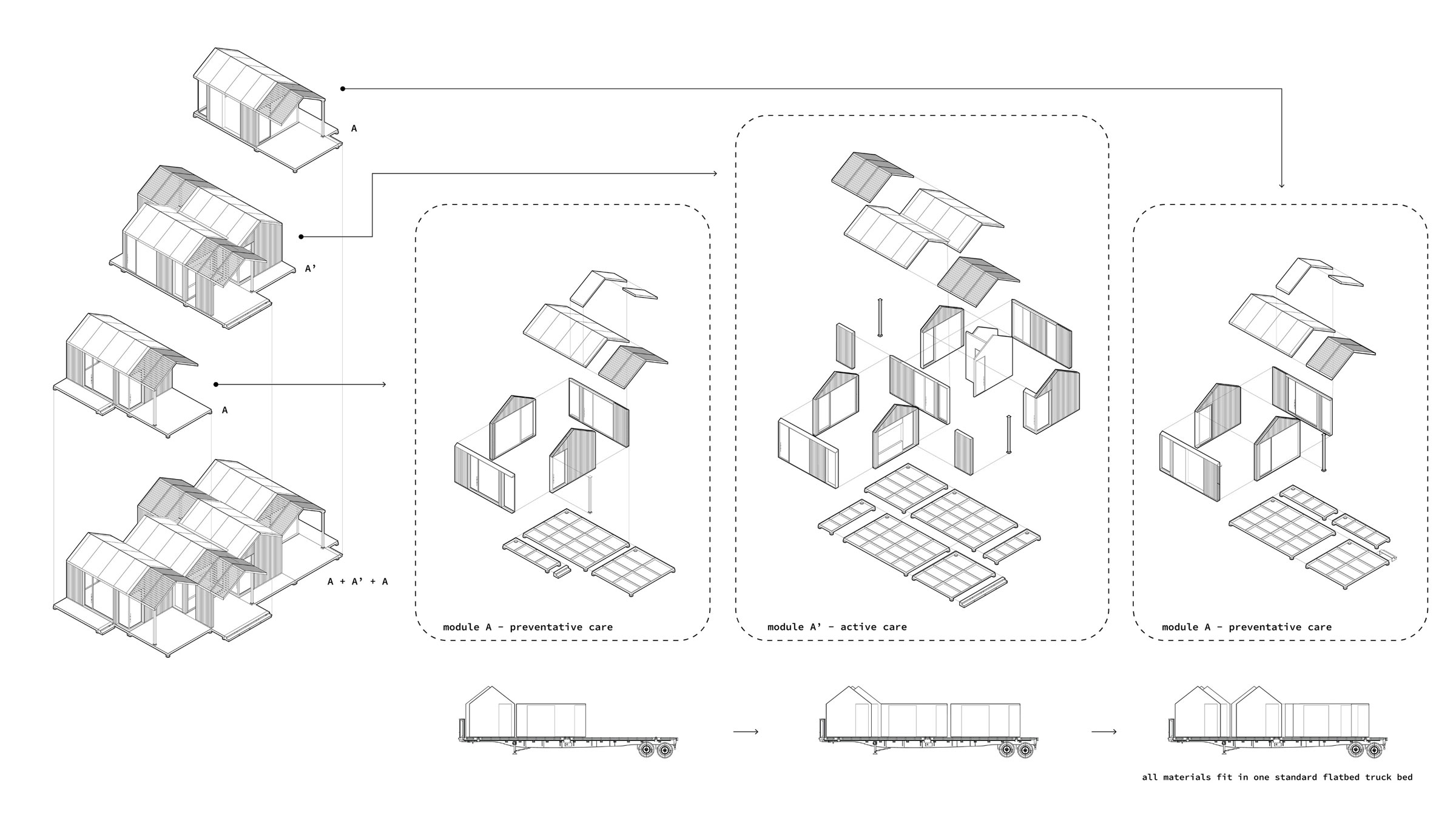

Logan Smith, BArch ’22, brought elements of the outside in with a structure made of lightweight wood and edged in sweeping windows, allowing for natural light and ventilation potential.

The natural antibacterial properties of wood made it an ideal surface, and the structural quality of certain timber, namely CLT (or cross-laminated timber, composed of glued layers of solid wood), could reduce the number of components required to build, speeding up the pace of construction. Smith also proposed prefabrication as a means to set up clinics fast, with walls sized to fit on the back of a standard flatbed truck and delivered complete to the building site.

This clinic would comprise several modules, for preventive care—testing and vaccination—and active care—reception, labs, storage, and patient rooms—with distinct outdoor areas for patients to wait, staff to receive deliveries, and clinicians to come and go. Smith also suggested that the structure could expand and include zones for reflective space for caregivers, “a neutral space of empathy, so physicians have the ability to restore their mental health as they fight against the virus.” For the safety of its occupants, each module houses its own airflow system, using displacement ventilation, which feeds fresh air in at floor level to push contaminated air up and out via exhaust ducts.

Smith’s site search engaged some of the social issues around care accessibility, pulling data on median household income and medical deserts in New York City. A partially cleared lot in Brooklyn’s Greenwood neighborhood, reflecting the lower end of the income scale, had the right mix of distance from hospitals and walk-in clinics but proximity to public transportation to establish need and potential impact in a health crisis.

“Architects are constantly battling a thousand different variables,” commented Ted Ngai, visiting associate professor of undergraduate architecture at Pratt, at the final review for the studio. “So we take that one variable that we want to learn a little bit about and expand it. How do you solve a larger issue—it’s not just a biological virus issue, it’s social, it’s cultural.” The projects developed in Micro-Infrastructure and the Epidemiology Clinic, to paraphrase Ngai’s remarks, begin to demonstrate that possibility.

In this studio, Seong felt students were able to bridge distances between architectural technology and human need in ways she had not seen in prior studios. While the clinic focus may change, the degree to which a studio was able to define and work from an empathetic vantage is something she hopes can evolve moving into the future.