Purvi Shah knows the anxiety of waiting. Waiting for the delayed doctor’s appointment to begin, waiting for the uncertain outcome of test results, waiting as treatment took its course for her young son as he battled the disease that forever changed her family’s life. In that liminal space reigned by chaos, Shah knew she needed to create a haven for her son and his older brother—and later for hundreds of other children and siblings experiencing cancer.

Shah’s son Amaey was first diagnosed with leukemia in 2005, when he was just three years old, on the day before Thanksgiving. For the next two years and nine months, Amaey underwent treatment, and life in and out of the hospital—countless hours in the waiting room—became the new normal. At the most turbulent time, Shah turned to something that for her had always been grounding: art making. At first, she describes, it was an act of self-preservation—but at its core, it was an act of love.

“I was selfish when I started creating art with my son who was going through leukemia treatment and his older brother,” she says. The illness, the treatment, the side effects, “I could not control any of that, but the small art projects we created, I could control them.” She watched their shared work transform the atmosphere, bringing laughter and color to days that might have been fogged in by stress and sadness. “I looked into the moments that my son was the happiest and most peaceful despite his cancer. They were when he was creating art in the hospital therapy room, in the hospital playroom, at home. Art was giving him a chance to create a world he liked.”

Seeing her son’s joy and, in the waiting room, other children’s and families’ curiosity, Shah began to encourage others to join in. “Little did I know that most caregivers felt like I did; they needed an escape, and our art workshops were just that,” Shah says.

In 2008, Shah arranged a special workshop to take place at Pixar Studios in the Bay Area, where she is based, imagining it would be a special, if one-off diversion for the families she’d befriended. The power of that experience resonated far deeper than the temporary escape. That first excursion led to an exhibition and auction of the children’s work to raise funds for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society—with physicians from the hospital in attendance not as caregivers but as art appreciators—all of which added a new level to the workshop’s significance. When the children saw their work transformed into something others admired and even acquired, they expressed a new sense of pride: Here, they were more than patients or siblings defined by a disease. They were makers, thinkers, and dreamers with voices in the world.

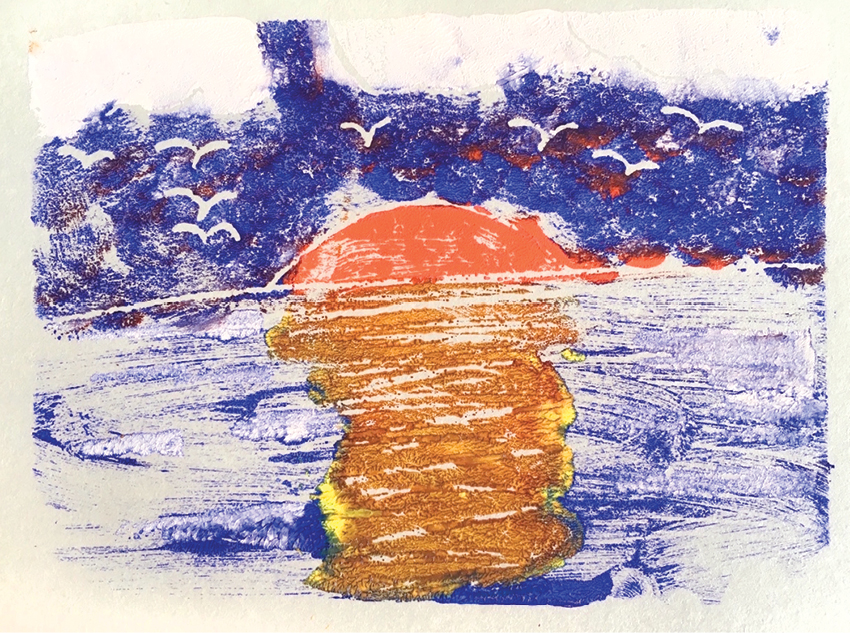

To continue the momentum, Shah established the Kids & Art Foundation. This year, the nonprofit organization celebrates a decade of providing moments of solace, reflection, and enjoyment to children and their families grappling with pediatric cancer. Waiting-room workshops led by Bay Area artist volunteers remain at the core of the foundation’s programming, held weekly at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford and UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital, and special destination workshops hosted by local creative meccas such as DreamWorks and Google are part of the annual calendar. The organization also created a special visiting-artist program for children in home hospice care. Then, just as in the beginning, the children’s work is exhibited. This year, young artists showed their paintings, sculptures, and mixed-media pieces at the Palo Alto Art Center, the San Francisco Women Artists gallery, Art Attack SF, and the San Francisco Airport’s Terminal 1 through the SFO Museum.

Shah set aside her career as a creative director to be a full-time caregiver to her son during his illness, but her instincts as a designer remained—and remain—a guiding force in her life. To develop a program that served the unique emotional and social needs of children and families grappling with cancer, she relied upon the strategies ingrained in her from studying communications design at Pratt, as well as applied arts in India, where she grew up, and her years coming up with solutions for clients such as DreamWorks and BlogHer. “It became who I am. I had to find beauty where there was none. I had to find happiness when there was none,” she says. Shah discovered an answer in observing how meaningful art making was to those around her. There was optimism in the “simple task of choosing a color or a paper” instead of focusing on the stress and pain surrounding treatment.

Art making offered opportunities to make decisions, rethink and restructure, problem solve, and determine when the work was complete—opportunities that cancer treatment can strip from children’s lives. For the kids, having agency over process is a big part of the work’s meaning. For parents, there is power in witnessing moments when their children are experiencing the uninhibited joy of childhood, when time melts away into simply being and constructing something new that the world has never seen.

From the start, Shah knew it was important for the workshops to take shape as opportunities, with guidance but not regulation: “The kids and families have too many rules, too many appointments, too many things they cannot do or have to be careful about,” she says, noting that the volunteers are trained to act as creative catalysts. Each project has many possible approaches, and art making is presented as a journey, with revision encouraged, along with cooperation and collaboration.

When building her Kids & Art team of staff and volunteers, Shah looked for focused compassion: “I wanted a team that was present. These children and their families are facing many challenges and they have to leave many things halfway. I wanted a team that understood the value of being there for each child and meeting them where they were, helping them complete their art so that they had a sense of accomplishment. It is a very small thing, making a piece of art while waiting for your treatment—it might even seem insignificant. To have a team that can come in with the empathy and vulnerability to see things as they are is very important.”

In 2011, Shah’s son Amaey relapsed with chemo-induced Acute Myeloid Leukemia. He passed away in September of that year. Amaey had fought cancer for six of his nine years. Shah says at that point, the will to look for the silver lining, the optimistic answer, felt distant to her, but one came to her nevertheless through the courageous spirit of her older son, Amaey’s big brother. “He wanted me to continue Kids & Art because for him as a sibling, the art workshops helped him escape and feel equally empowered,” she says.

The emotional and social challenges faced by children with cancer and their siblings, from anxiety to isolation and loneliness are well documented. The American Psychological Association lists among the potential effects of cancer on children forms of distress that include depression, anxiety, apathy, and low self-concept, which can be intensified by being away from school and peers. Siblings are often the silent warriors—managing an onslaught of complex emotions that can include feelings of neglect and guilt. A creative outlet can help them feel a sense of authority amid helplessness.

Shah has worked to establish a program that generates “a safe space where we do not prescribe anything. We let the kids be kids. We let the art do the talking and we create an environment that exudes hope, creativity, and transformation. Anything is possible.” Kids & Art has also begun to collaborate with hospitals’ established art therapy programs to offer projects that can be folded into formal therapeutic treatment.

In 2017, Shah received a Jefferson Award for Public Service for her work with Kids & Art. This summer, she transitioned from executive director to chair of the board, opening a new chapter to seek out ways to sustainably grow the organization—and she remains a vital presence at the workshops, often the first to show up and the last to leave, quick with a hug and a generous smile, echoed on the faces of the kids. “I attribute my background as a designer to who I am today and what I have done with Kids & Art,” she says. At Pratt, “the communications design program trained us to look for answers where there were none. Not settle for the mundane. Not wait for someone to solve your problem.” Because cancer threatened to stifle the joy and abundance of childhood for the young people and families around her, with tens of thousands more lives affected each year, Shah tapped into those problem-solving roots to create a solution with profound human meaning. “When I look at all the art created by both my boys and the other kids at Kids & Art workshops—when I look at the colors, the shapes, the stories weaved into each canvas,” she says, “I don’t see the cancer, I see the child.”