Although the planet’s biodiversity has been disappearing at an accelerating rate, efforts are currently underway to resist this decline and safeguard species. Pratt students recently learned about one such effort taking place at the Greenbelt Native Plant Center (GNPC) while working on their capstone projects as part of a Design and Nature studio taught by Adjunct Associate Professor of Industrial Design Esther Beke.

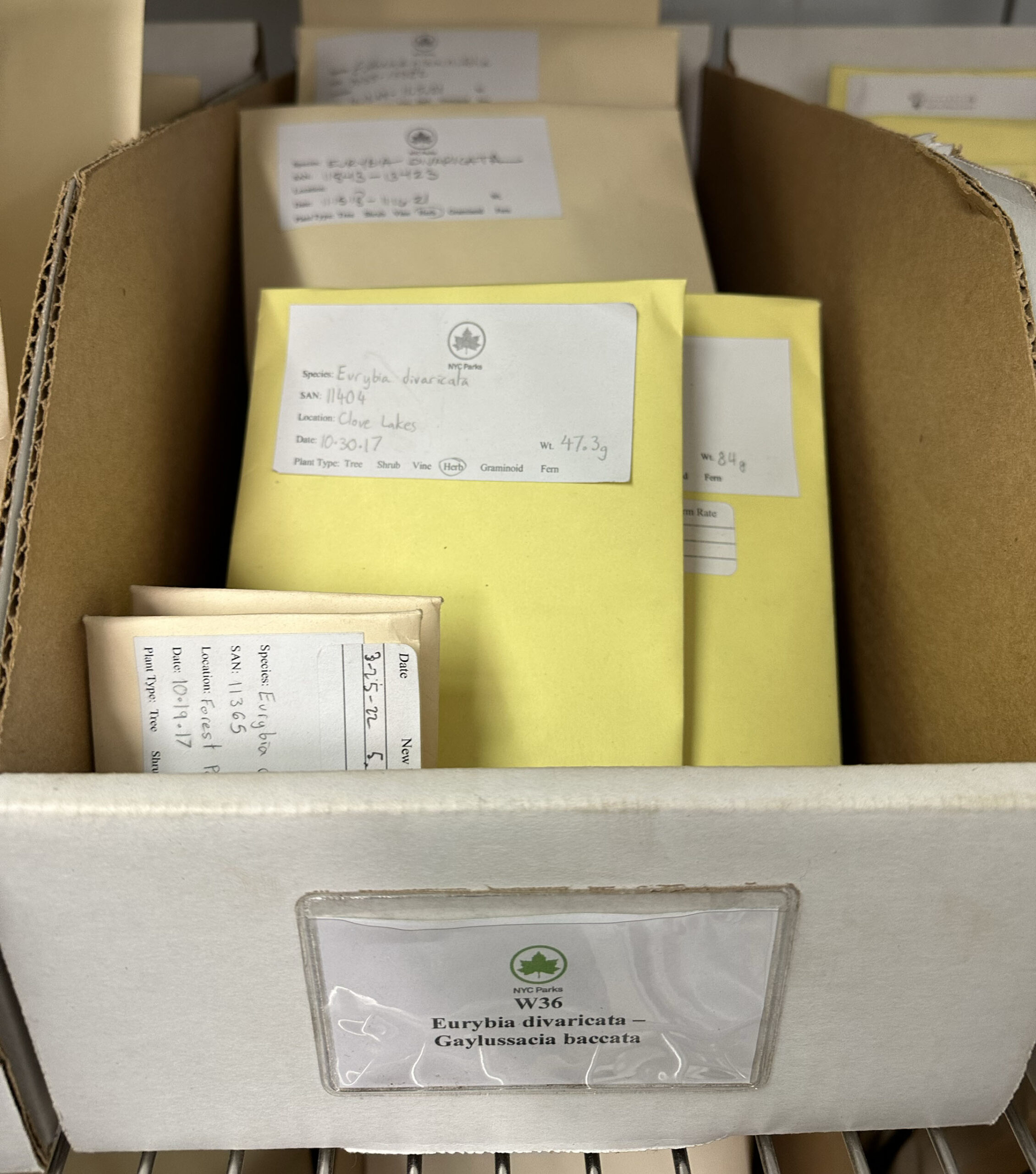

During their visit to the 13-acre facility, students learned that New York has more than 2,000 species of native plants, shadowed GNPC staff managing seeds and plants, and observed some of the work that goes into the ecological restoration efforts currently happening in the state. They also got their hands dirty while learning how to care for different plants.

“I wanted the trip to GNPC to broaden the way students think about design,” Beke said. “What would it look like to shift our design practice towards a more biocentric one, where we consider all species, not just humans? I asked the students to look at the variety of relationships that make up the natural world and then find places in which design can intervene in empathic ways.”

Students entered the class with senior thesis topics based on research from the previous semester, but early exercises in Beke’s Design and Nature studio gave these ideas more context and direction.

“With the initial two-week immersion into the world of native plants, which included a variety of readings, lectures, activities, and exercises, I was looking to enrich the students’ perspectives in how they consider the field of design, the needs for design, as well as their own research topics,” Beke said. “With questions like, ‘Can we reframe our relationship with nature?’ or ‘How can nature benefit from us?’, we started opening up possibilities for design projects that are meaningful, impactful, current, and necessary. Native plants were a gateway to biodiversity, and the consideration of humans within the whole diversity of species, which is a point of view that is not only broader but also more horizontal.”

For Kinako Miyake, BID ‘23, the studio has made her think more deeply about the dynamic between invasive and native species. Her capstone project aims to develop a more humane trap for spotted lanternflies.

“Humans are the ones who introduced these invasive species to the environment,” she said. “But they’re still living creatures. Just because it’s labeled as invasive, it’s treated as totally different.”

In New York, spotted lanternflies have been deemed an invasive threat because they feast on the sap of more than 70 native plants, making them vulnerable to disease, and secrete a dew that interferes with photosynthesis. Since the insects multiply extremely quickly, everyday New Yorkers have been advised to kill them. Some enterprising citizens have set up glue traps to catch them, but these tools have had the unintended consequence of harming birds and other wildlife.

Miyake’s trap works more like a bird feeder, with openings big enough for the lanternfly to enter, but small enough for birds to stick their beaks in to feed on the insects. Mesh netting on the outside would allow the birds to peck through and eat the insects for sustenance.

“I think that Etty’s exercise really helped to open up our eyes,” Miyake said. “Building for nature shows the relationships between other species and humans, and it shows how we can help biodiversity thrive.”

The capstone project of Myles Chisholm, BID ‘23, focuses on making hats that can ease social anxiety by modulating different senses. Despite making human clothing, Chisholm felt guided by the studio’s emphasis on helping biodiversity thrive.

“Each student is taking the inspiration that Etty collected for us and using it as a springboard,” he said.

Chisholm began his time at Pratt as a Fashion Design major. “I ended up moving to Industrial Design because I wanted a more holistic approach to design in general and manufacturing,” he said. “In recent years, especially while studying abroad in Berlin, I’ve been retracing my steps to wearable products, which was definitely inspired by my time in Fashion Design.”

Some of the other capstone projects include a game that helps children explore natural environments; designs to make hiking trails more accessible to the visually impaired; bioplastic made from coffee that can be used to make planters; toys made from ocean plastic; and a set of eccentric utensils that encourage human interaction.

As part of the studio, Beke’s students read a variety of texts, including passages from Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, a book that encourages readers to live in harmony with the natural world.

“One of the things that I love about that book is that Kimmerer opens up a discussion of like, okay, we look at the world as a place where we take resources, but we also have the opportunity to give back,” Beke said. “I think that designers have to think very deeply about how we approach the things that we make because this world only has so many resources.”

The Design and Nature studio asked students to think deeply about the environmental impact of their designs. Each project is being workshopped, refined, and improved with this idea in mind as students test out materials, incorporate feedback, and troubleshoot problems. The Pratt community and broader public will get a chance to see the final projects later this spring when they are displayed in May as part of Pratt Shows.