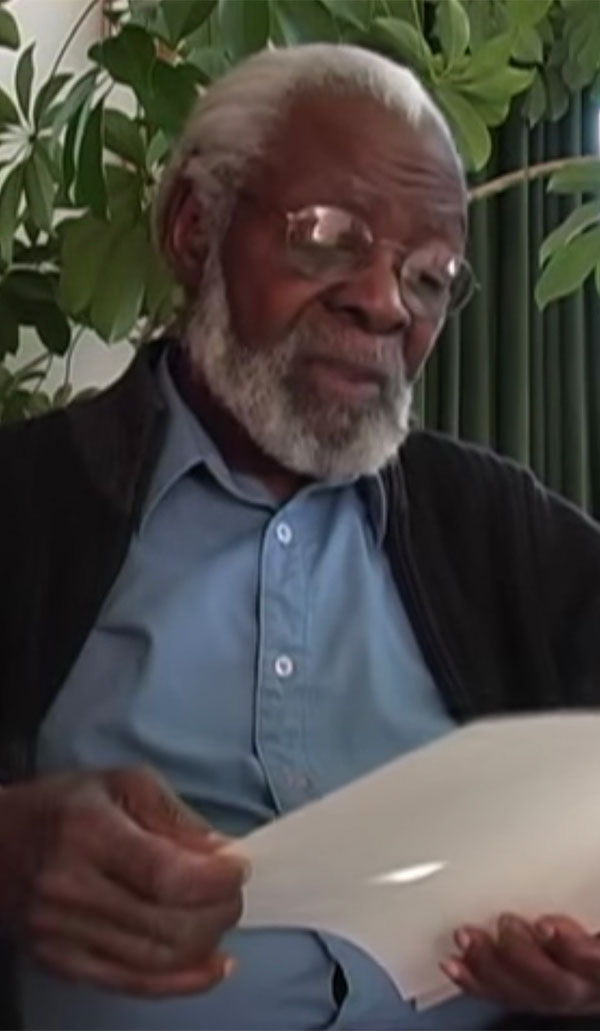

Cliff Joseph, BFA Illustration ’53, a pioneer in the field of art therapy who helped found the Graduate Creative Arts Therapy Department at Pratt Institute, died on November 8, 2020, the age of 98.

“We in the current department are proud that Cliff was a part of the early days of the Art Therapy Program which was one of the first art therapy programs in the country,” said Julie Miller, chair of the Creative Arts Therapy Department. “Founder Art Robbins said, ‘Cliff was a true pioneer in developing art therapy with hospitalized patients. His demonstrations of his work to students were memorable.’ And as we strive to meet the challenges of creating a more diverse and equitable department, we recognize his very early contributions to this effort.”

His legacy was remembered in a New York Times obituary which noted that he was the first Black member of the American Art Therapy Association and was a leader in “helping to introduce concepts like racial sensitivity and cultural competency to the profession.”

Born in 1922 to Caribbean parents in Panama, Joseph and his family moved to the United States when he was 18 months old and he grew up in Harlem. Following a stint in the Army during World War II, he studied Illustration at Pratt, graduating in 1953 with a Bachelor of Fine Arts. While he spent some time as a commercial artist, he was propelled by the civil rights movement to turn his focus to protest art. He explained in a 2006 interview entitled “Conversations With Cliff Joseph” that hearing the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963 “really awakened me” and led to a rethinking of what he could do as an artist to advocate for social change.

One of the major actions he was involved in was the founding of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition to push for the visibility of Black artists in museums. As he discussed in a 1972 interview for the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art, the organization was formed after the Metropolitan Museum of Art excluded Black artists from its 1969 Harlem on My Mind exhibition. “Our feeling is that art has a very vital part to play in the lives of people, not just aesthetically, but in terms of their real needs,” he said. “Many people don’t understand the way in which art can influence thinking and feeling and lifestyle.” He also participated in the 1971 Rebuttal to the Whitney Museum Exhibition organized by the Coalition in response to the Whitney Museum of American Art not hiring a Black curator for its survey of Black artists in the United States. Rebuttal was restaged in 2018 at the Hunter College Art Galleries and included Joseph’s “Superman” painting of a nude Klansman standing in front of a Confederate flag, carrying his robe, rifle, and other objects of oppression while his sallow skin rots away to reveal his skeleton.

Joseph’s activism for inclusion in the arts would fuel his career in art therapy where he saw the potential for healing through creative engagement that grappled with social issues. As he wrote in a 2006 article for the Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, therapists “need to recognize problems related to social reality and identify cultural resources available for struggle.” His work as an art therapist would foreground social justice, multiculturalism, and the necessity of systemic change.

Joining the Pratt faculty in 1969, he was pivotal in establishing the Graduate Creative Arts Therapy Department in 1970, one of the earliest such programs in the country. He taught at Pratt through 1980, leading both art therapy and social science classes. His belief in using art to confront the status quo as well as his promotion of equity in access to the arts remain key parts of the Creative Arts Therapy curriculum.

His pioneering work in art therapy included co-authoring the 1973 Murals of the Mind: Image of a Psychiatric Community chronicling mural sessions with patients in a university hospital, as well as serving as president of the New York Art Therapy Association. Throughout his practice, he strived to advance a democratic and participatory approach to art therapy and to empower marginalized communities to use art for healing. As he stated in the 2015 Becoming an Art Therapist: Enabling Growth, Change, and Action for Emerging Students in the Field, the “hidden agendas of racism continue and are exhibited in individual, organizational, and institutional settings, as well as in the mental health system itself.” He added that “interpersonal conflicts are best understood in the larger context in which they are bred” and that “organizing for change requires creativity.”

He was honored for his social activism in art therapy with a 2008 award from the American Art Therapy Association. As an educator, art therapist, and artist, he inspired generations of fellow creatives to use their abilities to contribute to a healthier and more equitable world.