As an artist, Alex Schweder—who was trained as an architect and has taught in Pratt Institute’s School of Architecture and Industrial Design and Interior Design programs for more than a decade—is not interested in design as a means of predetermining experience, rather, Schweder’s “performance architecture,” as he calls his practice, revels in the indeterminate possibilities that emerge from interactions between spaces and subjects. Projects like 2014’s In Orbit, in which Schweder and his partner Ward Shelley lived for 10 days on either side of a giant wheel, or the monumental ReActor (2016), in which the duo dwelled together in a slowly rotating Philip Johnson–like glass house, destabilize our common understanding of communal environments, particularly those tightly-shared spaces we call home.

Schweder and Shelley’s latest performance, Islands, wrapped up in mid-July of this year and completes a trilogy begun by 2017’s The Newcomers and 2019’s Slow Teleport. In this series, the two artists set themselves the task of traversing, over the course of 10 days, a large public space, constructing—and deconstructing—bridges and shelters as they live from day to day, all without touching the ground. Commissioned for the opening of the New Taipei City Art Museum, Islands introduced a twist: every few days, a resident of the peripatetic structure would be replaced. And so, as Schweder explained, the knowledge gained from experience would move not only through the open field surrounding the museum, but through time as well, from generation to generation.

I spoke with Schweder over Zoom, shortly after Islands was completed, about his interest in architecture and design as tools of social inquiry, how audience interactions—including consistent questions about the presence of a bathroom in his projects—influence and redirect his own, fluid understanding of his work, and more.

CLINTON KRUTE: Could you talk a little bit about the impetus behind Islands? How did this project come about?

ALEX SCHWEDER: Curator Kun-ying Lin learned of our performance Slow Teleport during a lecture I gave in Taipei in 2019. When he was asked to commission artworks for the opening of the New Taipei City Art Museum, he recalled my mention of continuous construction as a performance and thought it would be well suited for this event. My partner Ward [Shelley] and I said that we were happy to do something in that vein but that it would have to be specific to the context. So we went through our regular process of coming up with different ideas until we no longer knew who authored the final version, which is how we know we’re on the right path.

With Islands, Ward and I had been interested in involving younger people in our performances as a way of cultivating a next generation of thinkers—not that we want them to duplicate what we do, but we think engaging them is part of an experience of passing something along that will hopefully change in their hands. Islands is very much about that.

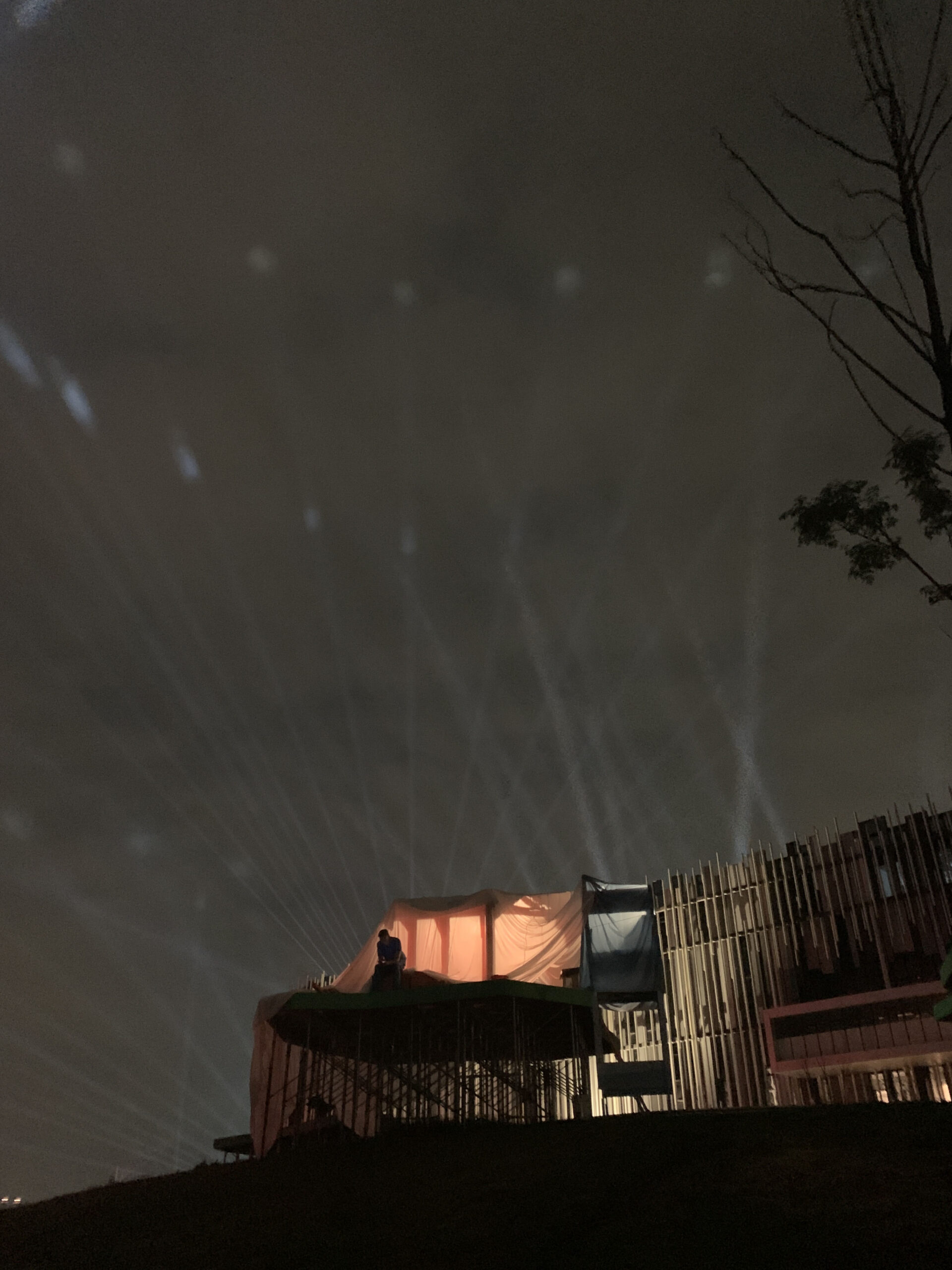

In this case, we set up these five islands, or elevated platforms, in an open field near the museum. Each island is about 6 x 7 meters, and has a different wooden structure or framework on top to be used as the basis for a shelter.

It was 95 degrees and 95 percent humidity, and it rained every day. But it was also a very wonderful experience. Most of the time was spent managing the wind. It’s a lot like being on a boat, where you are needing to navigate elements and navigate the people you’re with.

CK: I wanted to ask about the social element of your work, the way design can influence the way people interact.

AS: Design methodologies usually measure the success of outcomes based on the fidelity of the end result to what was imagined in the beginning. With performance, that line is much less direct. You can’t say, “We’re going to build something and it’s going to make people feel this way.” When I teach, I always want to help my students back away from claims like these. The performance architecture that I practice is meant to open up possibilities for subjectivity, rather than enact something that’s direct and linear. It creates circumstances out of which you don’t know what’s going to emerge. That, for me, is what is exciting about the way personhood and affect emerges through design, and through architecture in particular.

In the case of Islands, we were really interested in the way knowledge might be passed on through oral histories. Ward and I worked with two Pratt students, Hsiao-Chien Hung and Sean Lin [both MID ’24], whose roles as research assistants encompassed everything from materials research to translation to participation in the performance itself. [Editor’s note: Funding from the Pratt Institute School of Design Dean’s Office supported Hung and Lin’s participation as research assistants in the project.] We both started this performance with Hsiao-Chien, and then I left four days after we started, and Sean joined. Then Hsiao-Chien left and another artist joined. Then Ward left and another artist joined. Neither Ward nor I finished the piece. We ultimately left the participants, with two islands unexplored, to figure it out for themselves, without us dictating what they would do.

We depended on Sean’s and Hsiao-Chien’s fluency in Mandarin to have the conversations with our audience that are an essential part of the way we discover our work’s meaning. We always talk to people. It’s not the kind of performance where an audience is expected to just watch silently. We want the audience to engage us with their ideas and questions.

CK: Did you teach the new arrivals what you’d learned during your time on Islands?

AS: Yeah. The new person would work with the people who had been there and we would pass on what works and what doesn’t. Coming full circle, we found meaning in the idea that we needed to build a better house—and what better meant was really subjective. The urge to build a better house changed based on the group—there is no “better house” that exists out there as a Platonic ideal, right? Each island had, latent within it, the potential for various better houses.

CK: Your work is such a potent metaphor for living with people, and speaks very directly to our ideas about home.

AS: We see home as a kind of script. The activities of domesticity are super familiar, to the point that they are tacitly habituated. So our performance script is always: Just live your life at home. Try to go about your day. Because that’s so familiar to everybody, it allows our audiences to understand what we’re doing immediately. We don’t do anything differently except in our adaptation to the physical environment, which breaks the habit of the home. But the script is the same.

“We found meaning in the idea that we needed to build a better house—and what better meant was really subjective.”

CK: What kind of questions do people ask and what does that interaction do for you as a performer?

AS: What that interaction allows is a different perspective. We don’t step outside of our performance environments and look back in. We need others to help us determine the meaning of the artwork through dialogue that negotiates what we think we’re doing, what they think we’re doing. Somehow, in between those two positions is what’s actually going on. For Islands, as well as our other projects, we relied on our audience for that kind of reflective moment. An answer we give one day might change the next, because we’ve had this conversation the previous day that has changed our mind about what we’re doing.

Everyone asks, no matter what country we are in, “Where is the bathroom?” We thought originally it was just people trying to be funny, but over time we thought of this question as asking, “Can we trust you?” If there’s actually a bathroom, it means you’re not getting down. It means you’re invested. Once the audience sees that, they have an easier time investing themselves.

CK: Do you document those conversations at all?

AS: No, they’re oral histories. We want them to remain a non-authoritative, ephemeral, and fleeting thing.

CK: But they influence the work, like the weather.

AS: Yes. These works are not made to accomplish something discrete. Instead, out of each project, new ideas emerge. But I can’t say yet what new works will emerge from Islands. It’s too soon.

Islands performers, in order of arrival: Alex Schweder, Ward Shelley, 洪筱茜 Hung Hsiao-Chien, 林子翔 Lin Tzu-Hsiang, 徐莘 Hsin Shyu, 蔡承翰 Eric Tsai, 雷雅涵 Theresa Lei, 王甯 Ning Wang. Producer: Foison Arts