_copy.jpg)

Updated November 25, 2019

Across the United States, communities are grappling with how to address controversies surrounding Confederate tributes and memorials on public grounds. For example, the 5.4-mile Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, is a lush boulevard that intersects with some of the city’s most historic districts and architecture. Between 1890 and 1929, grand statues of Confederate leaders Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson, J. E. B. Stuart, and Matthew Fontaine Maury were erected along the avenue. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Virginia has issued a call to Governor Ralph Northam to remove the Lee statue from its pedestal and potentially relocate the Confederate general to the site of Lee's surrender, Appomattox Court House National Historical Park. Some preservationists have argued for keeping these Confederate monuments in situ.

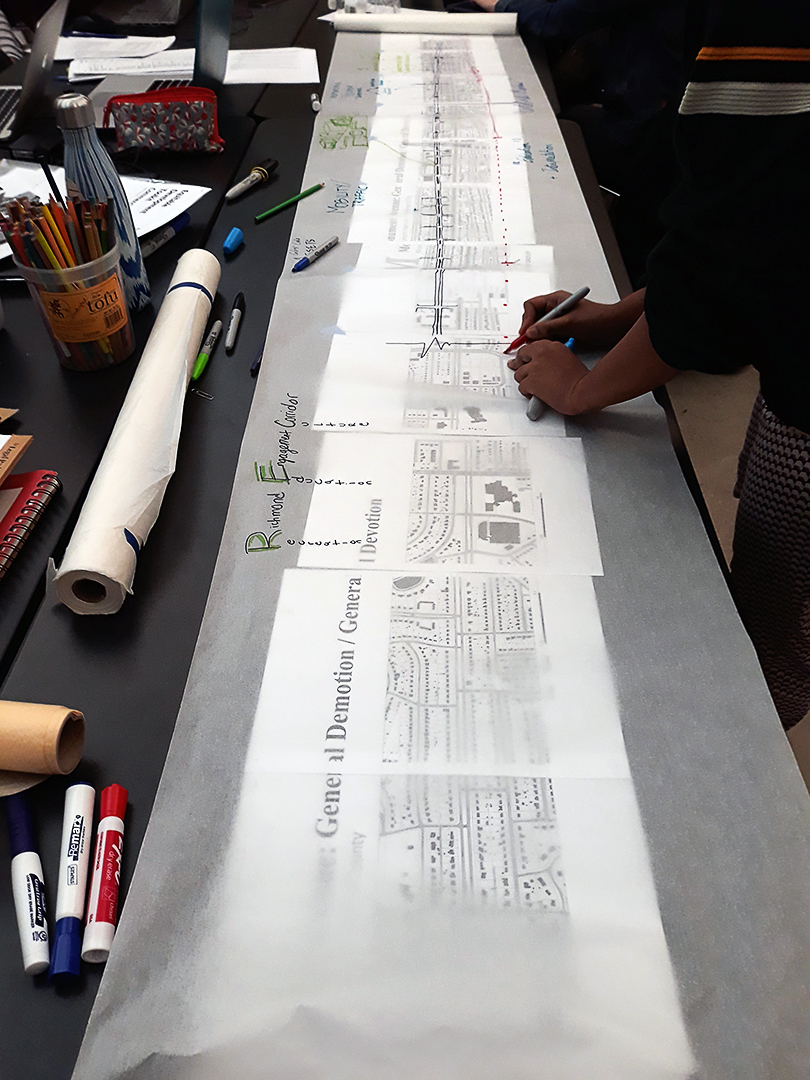

Two teams of Pratt students recently participated in an ideas competition to reimagine Monument Avenue beyond the binary solution of either leaving the sculptures in place or removing them entirely. Called Monument Avenue: General Devotion/General Demotion, it was initiated by the Storefront for Community Design and mObstudiO at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) School of the Arts.

Two teams of Pratt students recently participated in an ideas competition to reimagine Monument Avenue beyond the binary solution of either leaving the sculptures in place or removing them entirely. Called Monument Avenue: General Devotion/General Demotion, it was initiated by the Storefront for Community Design and mObstudiO at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) School of the Arts.

Both Pratt teams, each composed of students in the Graduate Center for Planning and the Environment (GCPE), traveled to Richmond to investigate the controversial corridor and the local relationship to it as a public space. One team was part of the Main Street Revitalization historic preservation class led by Dr. Courtney Knapp, Associate Professor of City and Regional Planning. Their submission was one of 20 Monument Avenue finalists on view through December 31, 2019 at the Valentine Museum in downtown Richmond. Called “The Richmond Engagement Corridor,” the proposal was selected by a jury panel as one of the four competition winners which were announced at a November 20 closing reception at the Valentine.

Making Monument Avenue a Vibrant Main Street

The Main Street Revitalization team, which included Claudia Castillo de la Cruz, Di Cui, Jane Kandampulli, Aishwarya Pravin Kulkarni, Danielle Monopoli, Maria Munoz Martinez, Dina Posner, Dhanya Rajagopal, and Camille Sasena, concentrated on two issues. “One is the fact that despite having a tree-lined grassy boulevard, there was no human interaction or chance encounter on Monument Avenue,” Rajagopal, MS Urban Placemaking and Management ‘19, said. “We wanted the avenue to transform into a productive public space.” The second issue was that while the avenue has significant strengths, including its prominent position in the city and its potential for robust community activities, it needed to attract more diverse groups.

Because their class was centered on the vibrancy of main streets, their proposal highlighted the avenue’s vitality as an economic and social hub. However, Monument Avenue is not just any main street, with its charged history and commercially-spare character, dominated by upper-class homes. To invigorate pedestrian traffic and social happenings, they proposed rebranding Monument Avenue as the “Richmond Engagement Corridor,” with regular programming connecting residents and visitors to the thoroughfare.

Because their class was centered on the vibrancy of main streets, their proposal highlighted the avenue’s vitality as an economic and social hub. However, Monument Avenue is not just any main street, with its charged history and commercially-spare character, dominated by upper-class homes. To invigorate pedestrian traffic and social happenings, they proposed rebranding Monument Avenue as the “Richmond Engagement Corridor,” with regular programming connecting residents and visitors to the thoroughfare.

“A traditional main street gathers the social life of towns and neighborhoods,” Castillo de la Cruz, MS Urban Placemaking and Management ‘19, stated. “Our approach maintains that idea but considers the challenges of a changing time and sensitivity. Monument Avenue is a source of a lot of debate and discussion, and it could be a place of agreement.”

As the class involved students from three different majors—Historic Preservation; Urban Placemaking and Management; and City and Regional Planning—their proposal offered interdisciplinary programming around the themes of culture, education, and recreation. Formal and informal discussions could encourage an ongoing dialogue on the past, present, and future of Richmond; street furniture and oral history booths could make the street more welcoming. Vacant buildings on the avenue could be rehabilitated into tourist lodging or incubators for artists and activists. Alongside these additions, the Confederate statues could be brought down from their pedestals to a more human level. Artists would then have opportunities to hide or reveal the monuments. New pavers embedded in the street could highlight local historical narratives that are currently invisible on the avenue.

“The proposal also stressed the need for long-term collaboration between different city, local, private, and community representatives, who could manage and program the space,” Rajagopal said. “Taking inspiration from Virginia's motto ‘Virginia Is for Lovers,’ we came up with something similar for the city of Richmond: ‘Richmond Is for Dreamers.’”

Honoring the Untold Histories of Richmond

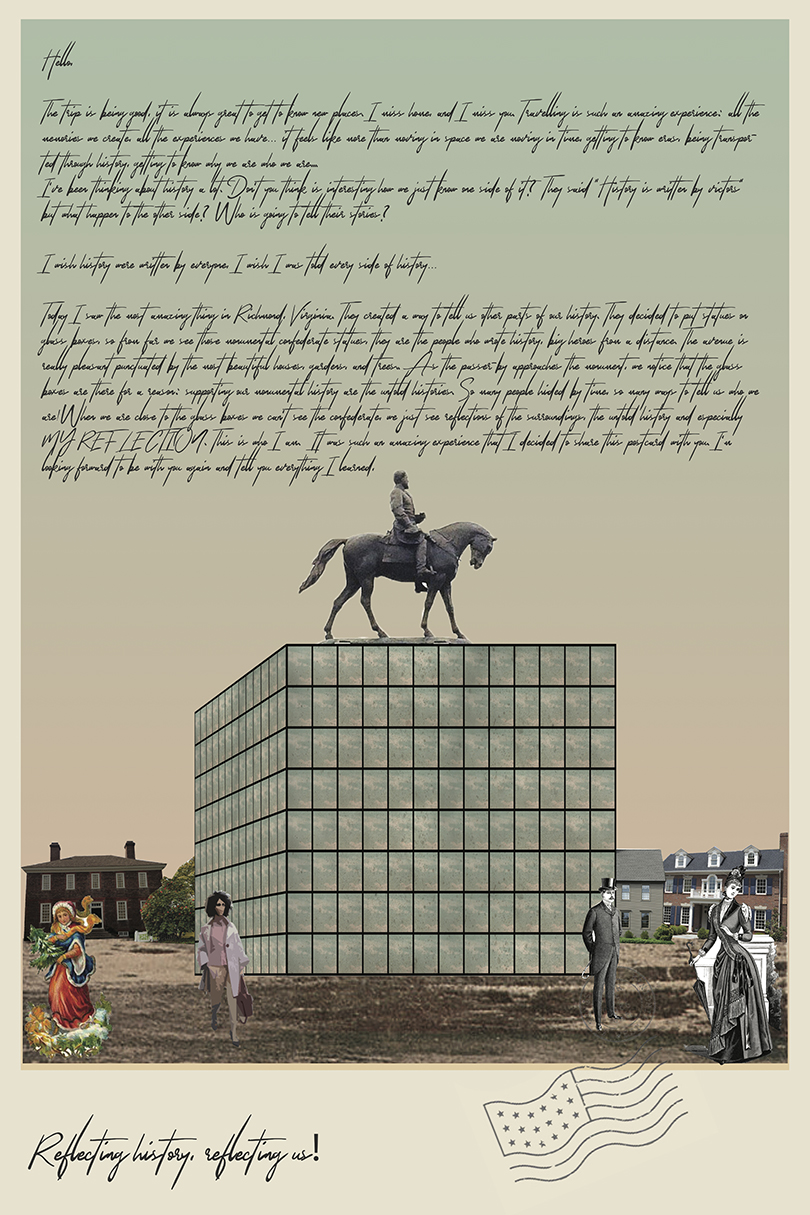

The other Pratt team, which included Taylor Kabeary, Eduardo Duarte Ruas, and Patrick Waldo, concentrated on reinterpreting the monuments themselves. Using glass blocks, the statues would be visible from a distance, but obscure when viewed up close. From that ground-level perspective, visitors could discover stories about the people these lionized figures oppressed. These interventions would ask visitors to question who is celebrated as a hero, and who is overlooked.

The other Pratt team, which included Taylor Kabeary, Eduardo Duarte Ruas, and Patrick Waldo, concentrated on reinterpreting the monuments themselves. Using glass blocks, the statues would be visible from a distance, but obscure when viewed up close. From that ground-level perspective, visitors could discover stories about the people these lionized figures oppressed. These interventions would ask visitors to question who is celebrated as a hero, and who is overlooked.

“Our team was very interested in uncovering the history behind why these statues were put up and by whom, and the larger impact they had on the community,” Kabeary, MS Historic Preservation ‘19, explained. “We did a lot of research on each of the monuments and the person it was honoring and decided to dig into whom the monuments were targeting. A lot of our discussions diverted into larger issues of untold or unacknowledged stories of minorities in historic preservation, and we wanted to flip the script on the people who made the monuments.”

Both proposals navigate the tension between the 21st-century city and these relics of the past through an emphasis on public space. They offer fresh pathways to inclusivity in places of collective memory and reshape them to better represent the current population. As Castillo de la Cruz said, “The corridor represents the opportunity for a critical social discourse that is needed in Richmond and the nation as a whole.

Images: The Main Street Revitalization historic preservation class in Richmond, Virginia (courtesy Courtney Knapp); The Main Street Revitalization historic preservation class developing their ideas for the Monument Avenue: General Devotion/General Demotion competition (courtesy Courtney Knapp); Students from the Main Street Revitalization historic preservation class at the Jefferson Davis Monument on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia (courtesy Courtney Knapp); The Richmond Engagement Corridor; Taylor Kabeary, Eduardo Duarte Ruas, and Patrick Waldo’s poster for the Monument Avenue: General Devotion/General Demotion competition (courtesy the students)