Almost eight decades since the end of World War II, art looted by the Nazis from the homes of Jewish collectors and others persecuted under the Third Reich continues to be recovered. Camille Pissarro’s “Rue Saint-Honoré, dans l’après-midi. Effet de pluie” (1897), for instance, is currently in Madrid’s Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection but was forcibly sold by Lilly Cassirer to the Nazis in 1939 to gain exit visas for her family to the United Kingdom. The case is now with the US Supreme Court as although the family has been attempting to restitute the painting since 1948, the museum has maintained they did not know it was looted when it was acquired. As paintings like the Pissarro have changed hands from the end of World War II through dealers, galleries, and collections, their return to the families can face these decades-long legal hurdles.

In the Mapping Provenance: Navigating the Narratives of Nazi-Looted Artworks project, Pratt Institute students are examining case studies including the Pissarro and other works, and using provenance data to bring new life to these stories. Led by Associate Professor Chris Alen Sula, the project is part of the Advanced Certificate in Digital Humanities offered through the School of Information. Each year, students are asked to design a project that will investigate how data can illuminate issues in the humanities.

“This course builds on foundational knowledge of digital humanities gained in the first semester of the certificate and invites students to work together to design and produce a digital project,” Sula said. “Collaborative work is a hallmark of the field, and students in this course get hands-on experience with project design, research, digital tools, and dissemination of their work.”

Previous years’ projects have included an exploration of Indigenous peoples, settler colonialism, and plants in North America; a study of the circulation of the term “fake news” following the 2016 Presidential Election; and an examination of “sousveillance,” the practice of monitoring the mechanisms that surveil. Each is selected based on the students’ ideas for the semester, with their work considering how information professionals can support digital humanities research through combining technology and inquiry into current topics and issues. As in years past, the project is culminating with a public website that acts as a resource for this research.

“When I was coming up with a proposal for our project this semester, Nazi-looted art jumped out to me as a project that could have an impact by educating on how restitution efforts are still ongoing and the complications surrounding them,” said Emma Boisitz, MSLIS ’22. “Especially when examining lost artwork or artworks that were previously lost, our current historical knowledge and the survival of materials and data are a matter of a string of fortunate circumstances. There is so much that is lost and it’s not always recognizable until you begin to dive deeper into the data.”

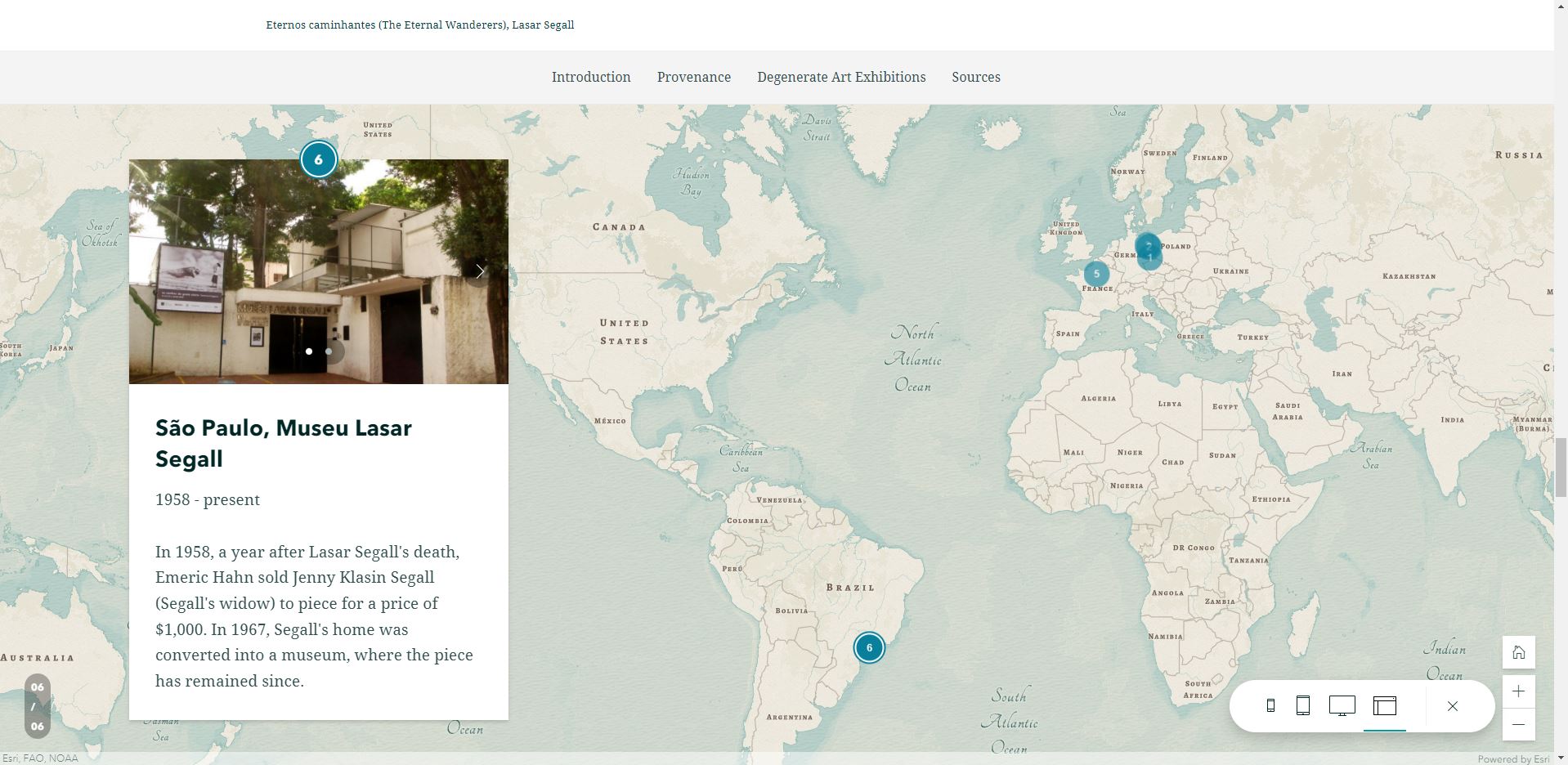

Journey of Lasar Segall’s “Eternos caminhantes” (1919), which was confiscated as “degenerate art,” in the Mapping Provenance project

The Mapping Provenance site includes maps following artworks that were looted as well as tracking the organization and exhibition of what the Nazi Party deemed “degenerate art.” Along with the well-known 1937 Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) show in Munich that was staged to purportedly reflect the moral decline of society through art movements like abstraction, Mapping Provenance shows other exhibitions across Germany that spread this intolerance, often featuring seized works of art.

“It brought up a lot of questions about how provenance data has been shared with the public, both by the Nazis but also in museums and exhibitions today,” said Miranda Siler, MA History of Art and Design ’22; MSLIS ’22. “The decision to share or obscure this information is definitely political.” Siler focused her research on “Eternos caminhantes (The Eternal Wanderers),” a 1919 painting by Lasar Segall whose work was confiscated from German museums and included in “degenerate art” shows.

Lasar Segall, “Eternos caminhantes” (1919) (via Wikimedia)

“When I took Theories and Methods of Art History as an undergraduate, I was left with the impression that provenance information was mostly useful for those interested in buying and selling art,” Siler said. “I now have a more holistic view with a lot of my work centering around the idea that an artwork or image’s meaning can shift and mutate over time with ownership and provenance a factor in this transformation.”

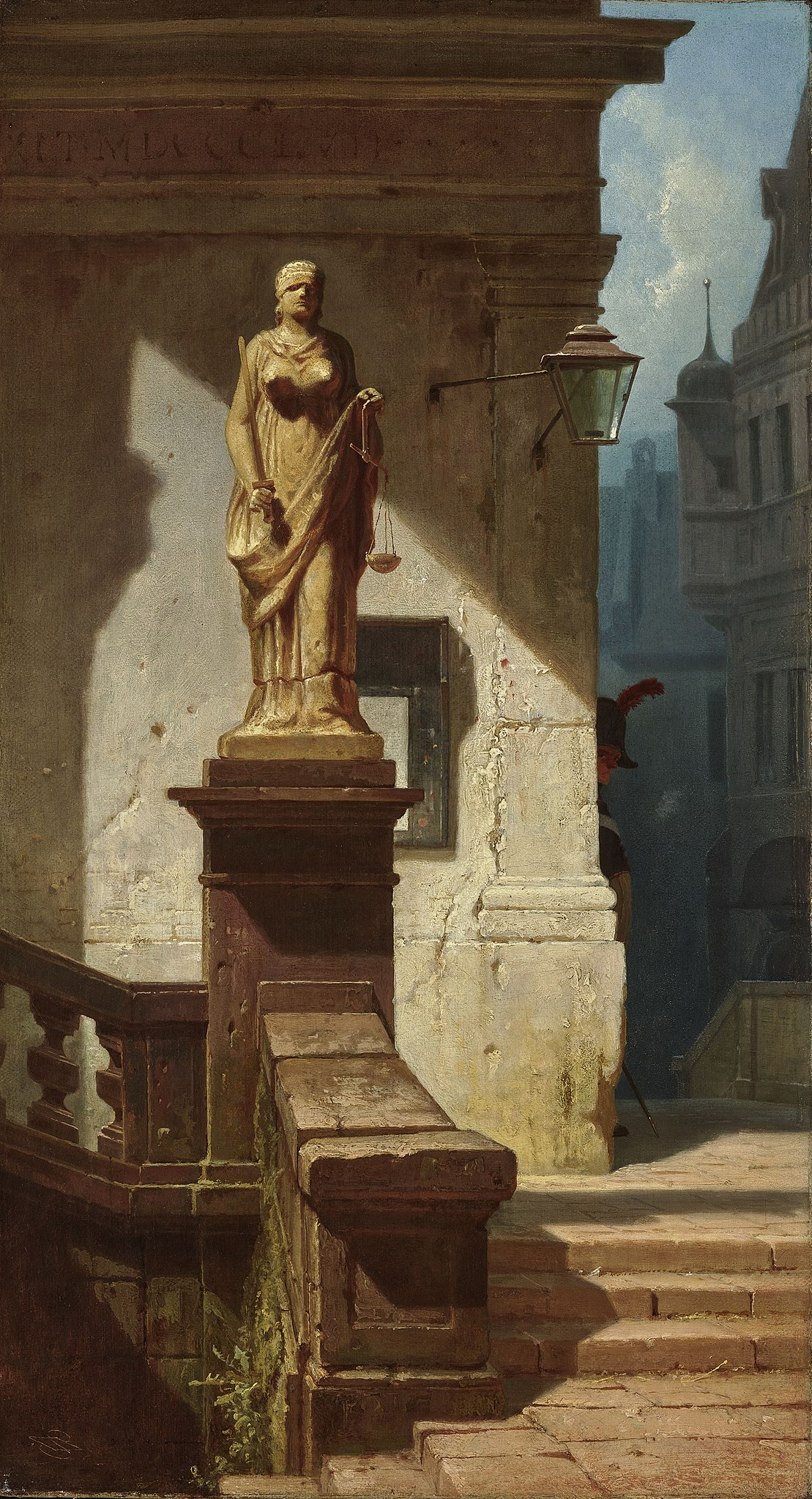

One of the students’ challenges was showing the many ways that art was looted under the Nazi regime, whether in forced sales from Jewish families who were fleeing the country or art that was confiscated by government institutions and committees. Another case study in Mapping Provenance is “Justitia” (1857) by Carl Spitzweg which was owned by Leo and Else Bendel. In their preparations for leaving Germany, they sold the painting to a Munich gallery in 1937.

Carl Spitzweg, “Justitia” (1857), oil on canvas (via Wikimedia)

Leo was ultimately arrested and died in Buchenwald while his wife survived, but she was not able to recover their art collection or receive compensation. Using archives in Germany and the United States and examining auction house information such as stickers on the back of the painting from various exhibitions and owners, Nicoletta Romano, MSLIS ’22, traced its route through salt mines outside of Austria where it was hidden from the Allies and later its installation in the German president’s office until it was finally restituted to the heirs in 2019.

Romano said that this project “has revealed the complexities of provenance information and research, especially in trying to map locations and dates where gaps or uncertainties may exist. Tracing the journeys of these artworks has made me reflect on the many intertwining narratives between these objects and the people associated with them.”

As with the Pissarro, not all of the artworks they mapped have been restituted. The process of returning them to the heirs remains complex, as laws vary from country to country and the statute of limitations has frequently long passed. By creating Mapping Provenance, the students are visualizing these complicated paths of looted artwork, taking available material on ownership, location, acquisition methods, and other details, often sourced from written narratives, and turning it into structured metadata to make it more accessible to researchers.

“One thing that’s come up during this project is learning to be flexible with research questions and being able to adapt to what you have in front of you,” Boisitz said. “A lot of provenance research hasn’t occurred yet or is ongoing and the data needed to do a large-scale analysis isn’t there yet. We were still able to do case-by-case analyses for several owners and artworks, but our focus has turned towards evaluating tools for future narrative-based provenance mapping opportunities and advocating for improving provenance metadata standards and sharing of provenance metadata.”

If this metadata were applied to a large number of such artworks, it could answer questions about geographic movement and the transfer of ownership that previously have been difficult to answer with data often scattered and available only in disparate forms. Craig Nielsen, MSLIS ’22, noted that the project has led him “to consider new ways of incorporating mapping and timeline visualization tools into my typical LIS research.”

As the ownership of looted artworks continues to be contested, having access to these narratives of objects is important for families and researchers reclaiming what was taken. For the students, it is also a way to connect to a history that is becoming more distant yet persists in its impact on the world.