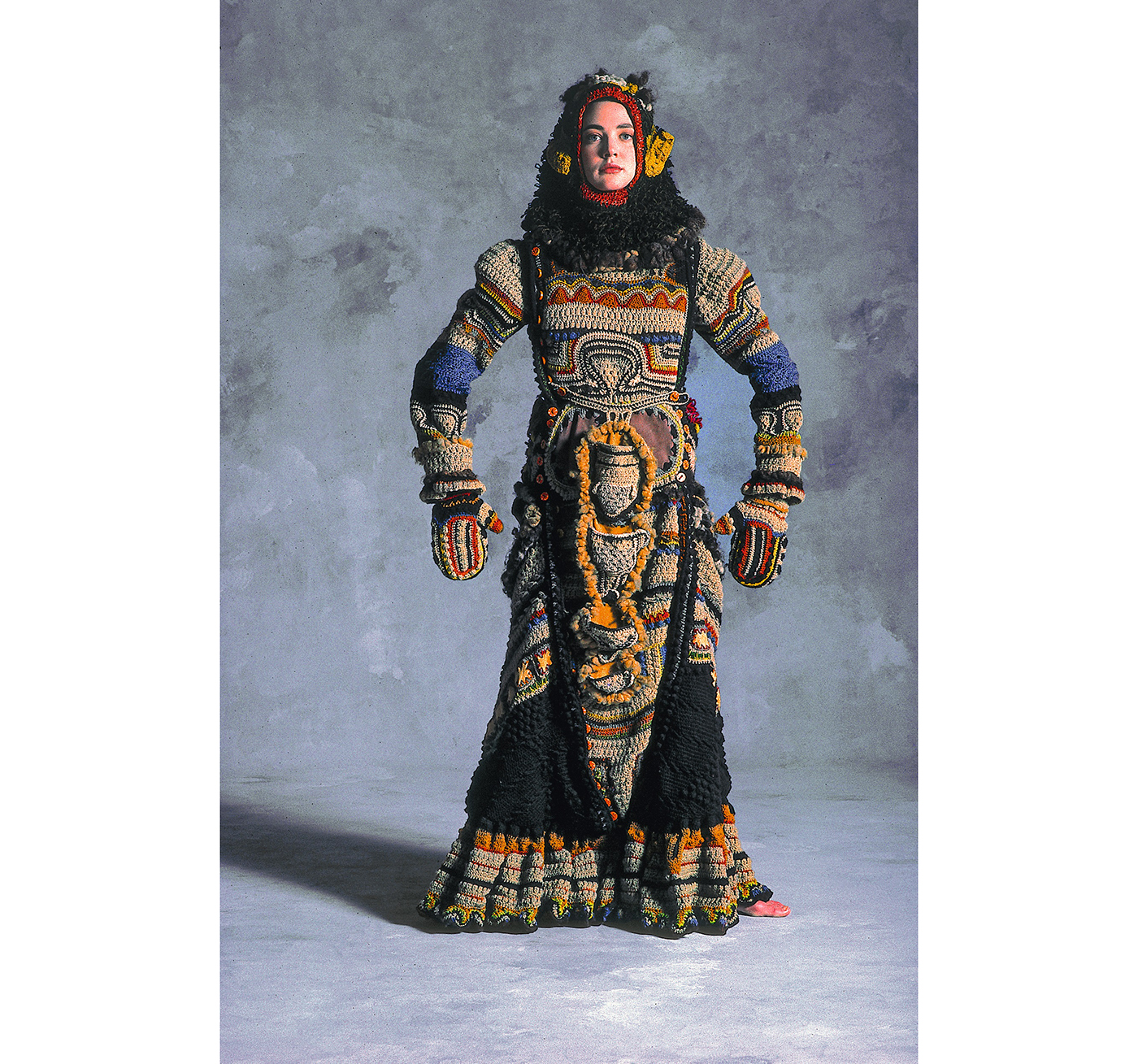

Jean Williams Cacicedo, Sharron Hedges, Marika Contompasis, and Janet Lipkin as students and at Off the Wall: American Art to Wear at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (courtesy Jean Williams Cacicedo)

In the late 1960s, a group of Pratt Institute students began crocheting their class assignments. The technique was not part of the curriculum and as they inspired each other they helped launch a new art movement. Art to Wear—also called Artwear or wearable art—emerged from the anti-establishment counterculture of the decade and reconsidered what art could be. Rather than static objects made for display in a gallery, the movement’s creations were meant to be worn as living art.

The five Pratt students came from different disciplines, studying painting, sculpture, graphic design, and industrial design. Yet they shared a passion for how textiles—long marginalized from fine arts—could offer unexpected materials for visual expression. Together, Jean Williams Cacicedo, BFA Fine Arts ‘70, Marika Contompasis, BID ‘69, Sharron Hedges, BFA Art Education ‘70, Dina Knapp, Graphic Art and Design ‘70, and Janet Lipkin, BFA Fine Arts ‘70, learned techniques that were not taught in their regular classes. Recognized as pioneers of the Art to Wear movement, the five Pratt alumnae have been featured this year in Off the Wall: American Art to Wear at the Philadelphia Museum of Art as well as an accompanying catalogue from Yale University Press.

Installation view of Off the Wall: American Art to Wear at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, with work by Marika Contompasis, Dina Knapp, Sharron Hedges, and Janet Lipkin (courtesy Janet Lipkin)

Installation view of Off the Wall: American Art to Wear at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, with work by Sharron Hedges (courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Pratt in the 1960s was rich with cross-pollination between departments as students tested the boundaries of their disciplines. “Textiles were still decades away from being seen as art, but Pratt still provided us a place of adventure, so when one friend learned a new technique, others learned it, too,” said Hedges. “That was how I ended up with an eight-foot wooden cube frame with crocheted rope netting inside for Sculpture, how Marika built a wire lounge chair with a painterly embroidered skin for Industrial Design, and how Janet sewed and crocheted a doll for Graphics.”

Contompasis was one of the few women in her Industrial Design courses and she was interested in how she could bring a “feminine perspective to design” as textile arts were traditionally done by women. Her chair was shaped like a flower with knit and crochet pieces that extended outwards, inviting the sitter to wrap themselves in the petals. Her work was strikingly different from that of her classmates, but the Industrial Design faculty, including her teacher William Fogler, were supportive of her experimentation with Cacicedo, Hedges, Knapp, and Lipkin: “We were definitely encouraged to use anything that was available. So we did and we all started learning these techniques with fiber and applied them to our work.”

Jean Williams Caciedo, “Chaps: A Cowboy Dedication” (1983), knitted, crocheted, felted, and hand-dyed woven wool mohair, wool jersey, and Dacron (courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, promised gift of the Julie Schafler Dale Collection, photo by Otto Stupakoff, © Julie Schafler Dale)

Cacicedo had learned to crochet from a neighbor while spending the summer at her family’s house on the Jersey Shore. Although it began as a hobby to pass the time, Cacicedo was enamored with crochet’s creative potential and how it was similar to drawing in its use of points in space to make lines, shapes, and forms. And because crochet was portable, didn’t require a machine, and could involve just about any flexible material, it offered limitless possibilities, perfect for the radical spirit of the 1960s. “The political atmosphere of our nation was in question, our values shifted from those of our parents, and we were hungry to explore new ways of thinking,” Cacicedo said.

Back at Pratt, she shared her new chain stitch and single crochet skills with her roommates, Lipkin and Contompasis. “We shared so many of our thoughts and attitudes about art and life and in non-competitive ways,” Cacicedo said, adding that “none of us really knew we were creating what is defined today as the American studio Artwear movement.” Their friends Knapp and Hedges were also teaching themselves textile techniques and they all began working together to engage in how fiber and the body interact.

Janet Lipkin, “Flamingo Jacket” (1982), hand-dyed, machine-knitted, and stuffed wool and angora (courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, promised gift of the Julie Schafler Dale Collection, photo by Otto Stupakoff, © Julie Schafler Dale)

“We were mentors and peers to each other,” Lipkin said. “As one of us discovered a new concept, it inspired each of us to grow and develop our own styles.” They innovated with color and organic forms, layering crochet into intricate textures. When these pieces were worn, a person was not just wearing clothes, they were transformed into a living sculpture. They could change how a person felt and how the world reacted to them. “The courage we young artists had at Pratt allowed us to explore a technique that was not used in artworks and still make art,” Lipkin said.

Dina Knapp, “See It Like a Native: History Kimono #1” (1982), painted, appliquéd, and Xerox-transferred cotton, polyester, plastic, and paper (courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, promised gift of Julie Schafler Dale Collection)

After graduation, the five artists stayed connected even as they dispersed around the country to pursue their own practices. Each was influential in making wearable art a movement. Hedges and Knapp remained in New York for a time, with Knapp later moving to Florida. Her detailed crochet included her “Fungus Jacket” which wrapped the wearer with rootlike forms. She also had a long career in performing arts, including as the wardrobe mistress for the Florida Grand Opera. She passed away in 2016.

Now working in North Carolina, Hedges has created elaborate pieces for home and fashion as well as textile design. Her dramatic 1970s and ‘80s coats used bright colors and expressive shapes to turn the wearer into something otherworldly, such as the vibrant butterfly wings of “Morpho” or the swirling colors of “Midnight Sky (Julie’s Coat)” made for Julie Schafler Dale whose New York gallery was an important showcase for the Art to Wear movement.

Sharron Hedges, “Morpho” (1984), crocheted and knitted rib, wool yarn, and wool jersey lining (courtesy the artist, collection Julie Schafler Dale)

Several members of the group moved to California, including Lipkin who has created dynamic crochet pieces that immerse wearers in color and form. One of her first works made following graduation, the 1970 “African Mask,” is now in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and completely consumes the wearer in a hand-dyed coat of hand-spun wool, leather, and wood. She also spent time in Africa and later learned machine techniques to pattern her works, such as her 1980s coats that responded to global destinations from Mexico to Tibet.

Janet Lipkin, “African Mask” (1970), wool, leather, wood (courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, lent by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Muriel Kallis Newman, photo by Otto Stupakoff, © Julie Schafler Dale)

Contompasis taught at colleges including San Francisco State, University of California, Berkeley, and the University of California, Los Angeles, and continued to investigate new techniques, including two-dimensional images in yarn before getting into high-end knitwear. Partnering with her brother and fellow Pratt alumnus Charles Contompasis, she founded MA+CH in 2002. The studio focuses on the entire process of sustainable design, from the dying of whole garments to the production and shipping of the pieces. Cacicedo also moved to California and had a stint in Wyoming, using a variety of techniques in her work that emphasizes handmade textiles. Her mythically-inspired art has ranged from large wall hangings and sculptural objects to wearable pieces, such as her 1978 “Pink Petals” jacket of appliquéd petals and knit sleeves that’s now in the collections of the de Young Museum in San Francisco.

Cacicedo said, “Pratt introduced me to possibilities through its academic diversity of disciplines, and with its teachers who encouraged learning the basics and looking beyond.” The friends have continued to share artistic knowledge over the years and remember how the creative environment on campus propelled them to make art as no one had before. As Hedges said, “Pratt fostered curiosity instead of pedantic lessons and its teachers allowed us to take chances, to move into unknown spaces, to bring out the images in our heads, to go with imagination.”