Teaching and learning at Pratt Institute changed rapidly this spring as the response to the COVID-19 pandemic forced a move off the physical campus, and into digital spaces. Among the classroom and studio practices that needed to be reimagined were modes of critique, a central element of many courses at Pratt. The digital and remote format presented a challenge for students and educators accustomed to the dynamics of traditional in-person reviews, but also potential as Pratt faculty members explored new models to further prepare Pratt students for a life of evolving professional practice.

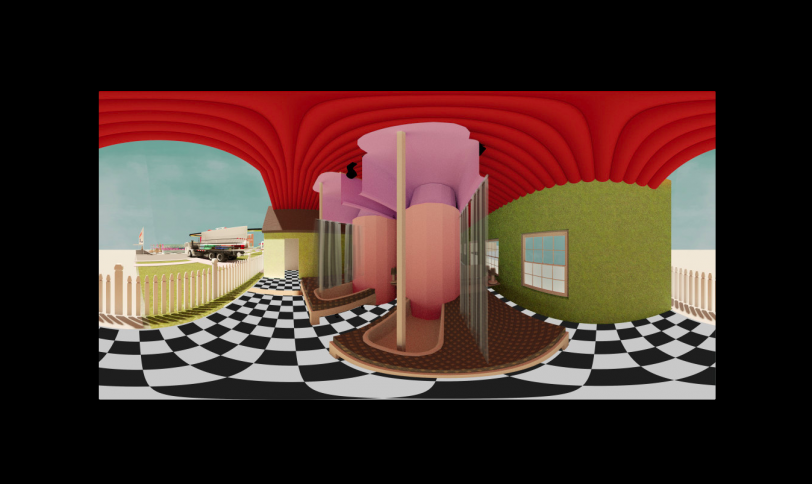

A frame from a 360-degree digital experience designed by Alejandra Sanchez Tata and Susana Chinchilla, both BArch ’20, that was part of their thesis presentation for Michele Gorman and Adam Elstein’s Architecture and Magic studio.

Teaching and learning at Pratt Institute changed rapidly this spring as the response to the COVID-19 pandemic forced a move off the physical campus, and into digital spaces. Among the classroom and studio practices that needed to be reimagined were modes of critique, a central element of many courses at Pratt. The digital and remote format presented a challenge for students and educators accustomed to the dynamics of traditional in-person reviews, but also potential as Pratt faculty members explored new models to further prepare Pratt students for a life of evolving professional practice.

Some professors saw an opportunity to expose students to a broadened network of practitioners, bringing in reviewers who under ordinary circumstances might not be able to attend an in-person critique.

Thomas La Padula, adjunct professor CCE of undergraduate communications design, had several Pratt alumni who are now art directors set to participate in reviews of graduating illustration students’ work this year. When the spring semester transitioned to remote teaching and learning, the alumni stepped up to offer their critique online. “They volunteered. I did not bend arms,” La Padula said. “I thought that was really great, and then a few non-alums volunteered.” In all, a dozen professionals from the realms of Scholastic, BuzzFeed, Scientific American, Ad Age, and other publishing entities joined the critique of senior illustration work. They reviewed portfolios on the site Submittable, which made its digital review platform free as a response to COVID-19, over a period of 16 days.

Patricia Madeja, coordinator of the Fine Arts jewelry program, also was able to welcome reviewers who may not have been available to participate otherwise. In a critique session held via Zoom, this year’s graduating jewelry majors were able to present to alumni of the program who are now educators as well as Pratt faculty from other departments, such as Communications Design. Wanting to help highlight the work of the graduates coming up behind her, jewelry alumna Xin Xu, BFA ’19, spearheaded the development of a digital platform for the reviewers to interact with the work. The platform, CritiART, which hosts images of work, written content, process videos, and gifs, allowed Madeja to also invite guest critics to comment in their own time on students’ final projects.

Professor Patricia Madeja’s senior jewelry students and guest critics gather on Zoom for their final review.

Reaching out to her international network, Amanda Huynh, assistant professor of industrial design, who came to Pratt last year from Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver, Canada, engaged her Pratt students with design colleagues from across the continent. “I’m excited to open up final reviews to friends outside of the Pratt community and New York City. Very grateful to have friends who are willing to get up at 6. on the West Coast in order to join me and my students,” Huynh said as end-of-semester critiques neared, in her newsletter Design in the Time of Corona, launched as another way to connect students to conversations in the larger world of design. A typical final review, Huynh noted, might include some three-to-five external reviewers, but one session this spring, for industrial design capstone studio Nourishment and Social Change, had more than 20 guests in attendance.

For 17 of his 22 years at Pratt, Professor Jon Otis has held a Career Night for both BFA and MFA students of interior design, who present their work to principals of major design firms. This year, the event—which Otis organizes with his wife, Diane Barnes, hospitality sales director of furnishings brand Haworth Collection—was moved to Zoom, preserving something of the face-to-face interactivity of the traditional in-person gathering.

Still, there were hurdles to overcome. “This was a big challenge for us,” Otis said. “This event is not only about face-to-face meetings with prospective employers, but it is focused on getting a job. Given the pandemic, we had to work very hard to get students to join in to the new format, with only the hope of potentially landing a job in the future with one of the participating design firms.”

The organizers’ efforts ultimately succeeded. “We were quite pleased with online attendance for the event,” Otis added. “It attracted more students than we often have at the live event, which, of course, involves a greater time commitment and travel into Manhattan. So in some ways, this has opened up new possibilities for future events connecting students to practitioners utilizing similar formats. It’s clearly not a replacement for the live event, but rather another effective implement.”

More than 75 students, faculty, administrators, and practicing architects and interior designers, several of whom are Pratt alumni, were in attendance as students presented their portfolios. The undergraduate and graduate portfolios were made available for review on the publishing platform Issuu, accessible beyond Career Night. The evening’s program also allowed time for reviewing panelists to share some of their perspective from the field—and to offer an additional layer of mentorship, reassurance, and empathy in this challenging time, particularly as some of the panelists had finished their education and started working during a similarly uncertain period, in the wake of 9/11.

For some faculty, critiques in the time of remote learning meant centering the voices of the students and creating opportunities for them to refine and clarify the language around their and their peers’ ideas.

Foundation professor James Lipovac, who teaches the courses Visualization and Representation and Light, Color, and Design, had students frame their progressing projects by writing about their research and project scope. Then, working in pairs, students edited and gave suggestions on one another’s writing.

“The critique became more about how the writing could better articulate what it was the artwork was attempting to do, and perhaps, whether the artwork needed to evolve to better address the conceptual underpinnings of the project,” Lipovac said. “The digital crit format has forced me to accelerate my designs for creating a classroom that relies less on teacher-centered critiques and more towards self-assessment and peer assessment.”

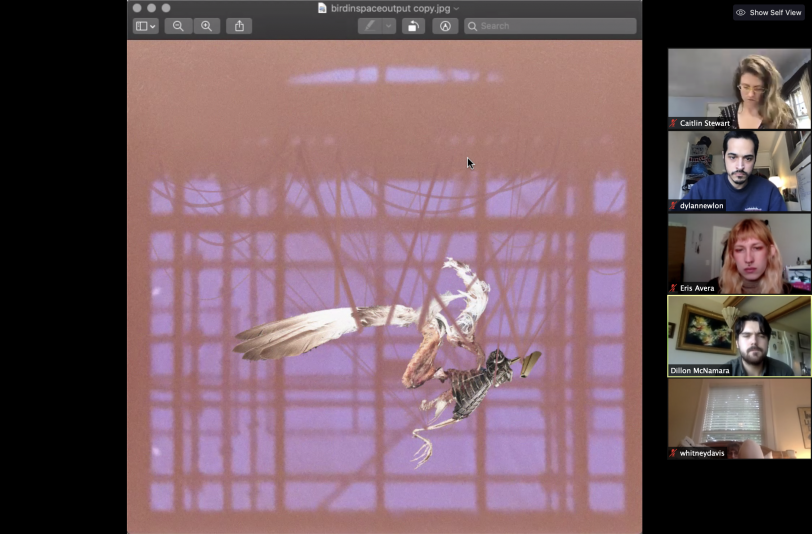

In one of fine arts professor Analia Segal’s spring 2020 courses, junior sculpture students met via Zoom for their final, discussing a collage by Dillon McNamara, BFA Fine Arts ’21, part of his research on the relationship between the natural world and the digital world.

Analia Segal, fine arts professor of sculpture and integrated practices, as well as area coordinator, also rethought the critique process to initiate reflection on concepts and process. Segal started with a revision of assignments for the remainder of the semester, amending the syllabus to adapt to the move from studio to home-based practice.

“I was emphasizing all the time: Here we are, all of us together on the screen. What is really happening? How can we turn this into something?” Segal says. “The screen is both a mirror and a window. Based on those concepts, I started creating assignments for students to become very aware of their surroundings in a new way, being empathetically present.”

Critique became more about discussing work in progress. The idea was not to produce work in an effort to remain productive, “but really to be open to mutating and embracing everything that was around us. . . . It was a leap of faith at the beginning, but I felt that it worked really well. The students were a lot more engaged in experimentation, making new discoveries in the process, than in a final product.”

Indeed, the restructuring of life—in the classroom, in the studio, and in the world at large—brought on by the pandemic has sparked many faculty to reimagine critique in ways that could have continued resonance into the future.

For example, Michele Gorman, adjunct associate professor of undergraduate architecture, observed that a presentation framework that relies on expensive final physical models or printed, pinned-up drawings—difficult to execute in the current situation—is also “a wasteful practice that only adds to the environmental crisis.” Students’ methods of presenting work could become a site for continued innovation.

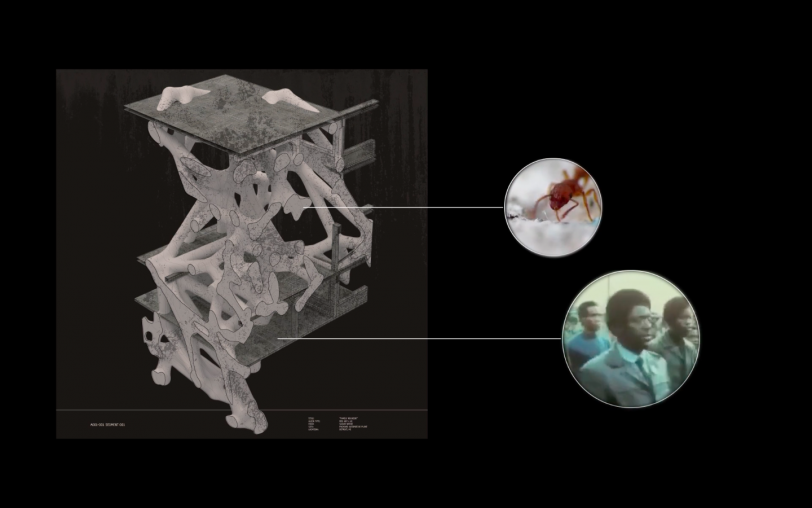

A still from the presentation for thesis project You Will Never Understand by Joshua Cooper, BArch ’20, shared on Vimeo, for Michele Gorman and Adam Elstein’s Architecture and Magic studio.

During the spring semester, Gorman saw students shift their projects to digital presentation formats with relative ease, taking advantage of existing publishing tools like WordPress sites that can be created through Pratt Commons (such as the one for Gorman’s Architecture and Magic studio, taught with Adam Elstein, adjunct assistant professor of undergraduate architecture), and video platforms such as Kaltura, Vimeo, and YouTube. Students also utilized 360-degree virtual-tour applications, creating immersive experiences like the “liquid suburbia” designed by Alejandra Sanchez Tata and Susana Chinchilla, both BArch ’20. “Reviews are made interactive and immersive in 360 virtual environments, which is necessary to facilitate constructive feedback,” Gorman noted.

With the capability of these sites and tools to broadcast their presentations widely, students have also taken on the added challenge of adapting the way they communicate about their work, focused on, as Gorman remarked, “clarifying their narratives for a more global audience.”

In a time of shifting paradigms and reconsideration of familiar modes of learning, work, and life, the Pratt community’s focus on creative inquiry, research, and innovation uniquely positions students to confront the challenges of today and those to come. The shift to digital formats for critique has unlocked new methods that could inform future critical practices and revealed the broad network that supports and champions students’ and recent graduates’ ongoing work.