There are 31 bridges that span Seoul’s Han River, most of which were built during the 20th century, when urban planners pursued programs of rapid industrialization. Now, as the impacts of climate change increase in the region, including catastrophic flooding events, new efforts to protect biodiversity and public health are underway.

The fourth Seoul Biennale for Architecture and Urbanism 2023 invited architect and design teams from universities and colleges worldwide to propose modernizing bridge designs for the Han River as part of a larger reimagining of urban life in the century ahead. Student groups were asked to boldly experiment as they considered ways their designs could promote food and clean water access, green space and biodiversity. A total of 113 designs from forty international schools were submitted and, of the 12 finalists, two Pratt projects the School of Architecture were selected—one graduate and one undergraduate.

“Both studios took concepts and techniques that we’re working with here at Pratt and pushed them into new realms,” said Mark Rakatansky, visiting associate professor of undergraduate architecture, whose students displayed their work at the Biennale. “In engaging with Seoul and its conditions, the students created whole new symbiotic possibilities for design and architecture and showed that the future has to be now because that’s where we are now.”

Members from the two groups traveled to Seoul last spring to learn more about the city and its built environment and meet with local architects and designers. They also toured the Han River to better understand its ecology and how it supports urban life.

“On Google Earth, you only see this blue plane, but when you go there you see the wildlife, the birds, the way that the water flows. We noticed that it flows really slowly and it’s really shallow,” said Guillermo Garza, BArch ‘24. “We saw the way people use the banks of the river. We saw people constantly running across it, exercising on it, and fishing. You can’t really see that on Google Earth. The river became this thing that’s really alive.”

Beacons of Possibility

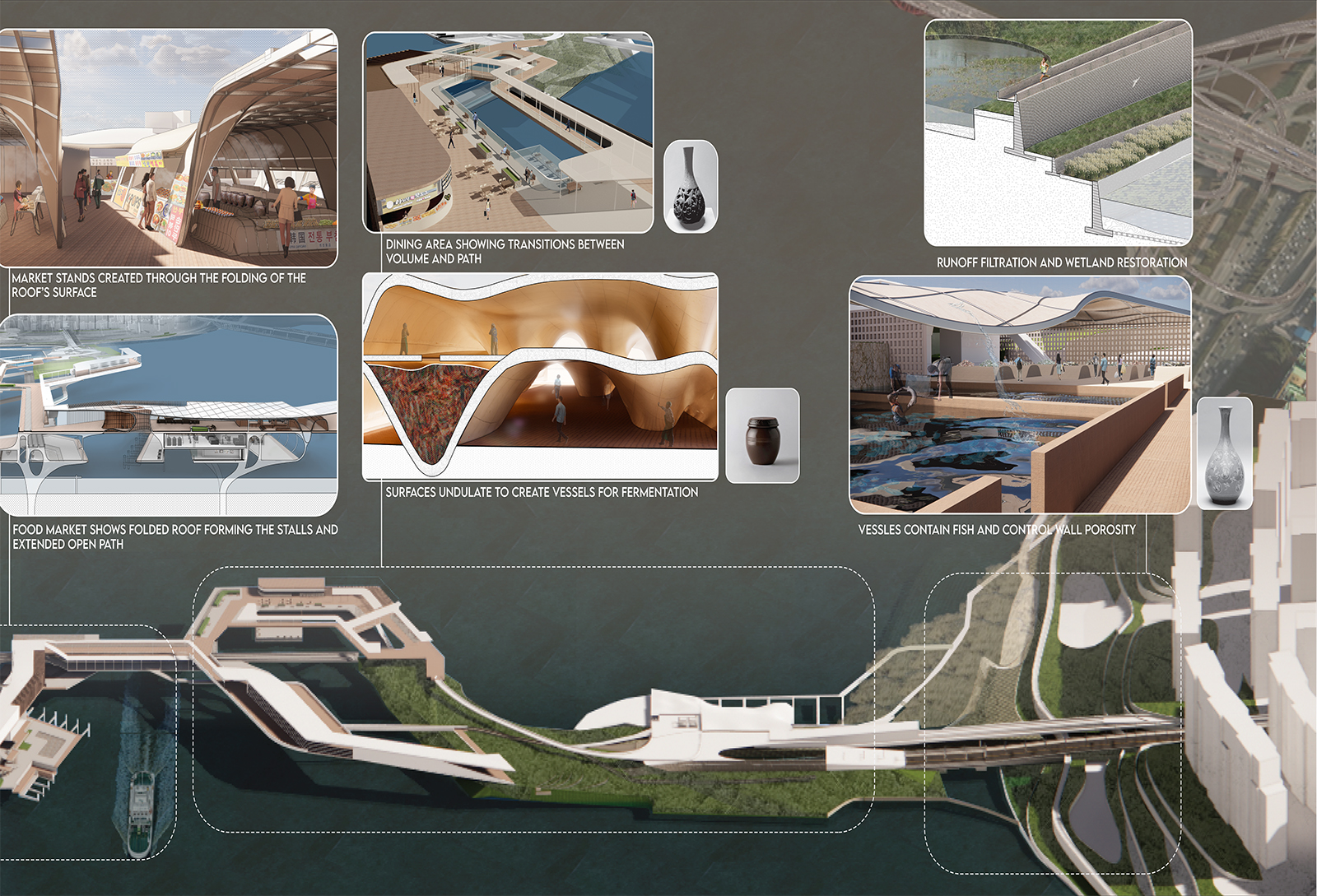

The “Manifesting Vessels Across the Han River” project by Alyssa Conde, BArch ‘24, Garza, and Aura Wang, BArch ‘24, emerged from Rakatansky’s undergraduate studio Bridging the Mega-Micro City: Inhabiting Our Natural Histories.

Students used specific Korean cultural elements to tie together the project’s environmental, social, and economic concerns. In the case of the “Manifesting Vessels” design, students envisioned a bridge that functions as an ecological rehabilitation corridor and expansive community space. They drew on the long history of Korean ceramics by proposing clay-based wildlife sanctuaries built into and throughout the bridge.

“I specialized in most of the things regarding clay because I used to be a tile worker and I know its properties,” Garza said. “I was actually really happy when we were researching the project and learned that pottery and clay were really big parts of Korean culture.”

“The bridge is having this dialogue with the river and Korean culture through the way clay is collected and cleaned and shaped,” Garza said. “It’s not just a bridge on top of the ground, but exists instead as an integral part of the ground. The ground speaks to the building and the building speaks to the ground.”

The elegant contours of traditional ceramics can be seen in the design’s broad walking paths and commercial marketplaces where local vendors and artisans can sell their goods. Dedicated greenhouses allow for aquaponic farming and fermentation practices, while porous platforms filter water, addressing water scarcity. The road is set below the river’s wetland curb, minimizing noise pollution, improving air quality, and decentralizing vehicles.

With these varied purposes, the design contributes to the global movement to reclaim cities for pedestrians. It’s also a powerful social intervention as it would encourage community engagement and commerce, and mitigate pollution through green space.

The Seoul Biennale aims to foster more equitable forms of urban design to help communities adapt to a precarious future, and Rakatansky thinks that the perspectives gained throughout the semester will serve students in their professional lives.

“I believe that every commission has the potential to be the commission of a lifetime no matter how small or large,” Rakatansky said. “I want my students to believe that they don’t have to wait for a bridge over the Han to engage deeply with these same issues.”

Two additional undergraduate projects from Rakatansky’s studio were presented in the exhibition. Haoran Li, BArch ‘24, developed the “Bridging a Permeable City across the Hangang River” project, which proposed structures and infrastructures to foster a more interconnected and sustainable urban environment. And the team of Weilin Berkay, BArch ‘24, Seoyoon Lee, BArch ‘24, and Sam Miller, BArch ‘24, proposed an archipelago formation of constructed islands linked through the exchanges of cultural programs with renewable energy and water purification systems entitled “Powerpelago.”

The Future of Urban Development

Graduate students in the Fair Structures: Seoul Biennale studio taught by Jonas Coersmeier, adjunct associate professor-CCE of graduate architecture and urban design, displayed “Painterly Urbanism” at the the Biennale, featuring work from Daniela Abella, MArch ‘23, Yazeed Alamasi, MArch ‘23, Sokaina Asar, MArch ‘23, Nicole Mourad, MArch ‘23, Danielle Pelletier, MArch ‘23, Bex Romero, MArch ‘23, Dana Saari, MArch ‘23, and Ekam Singh, MArch ‘23.

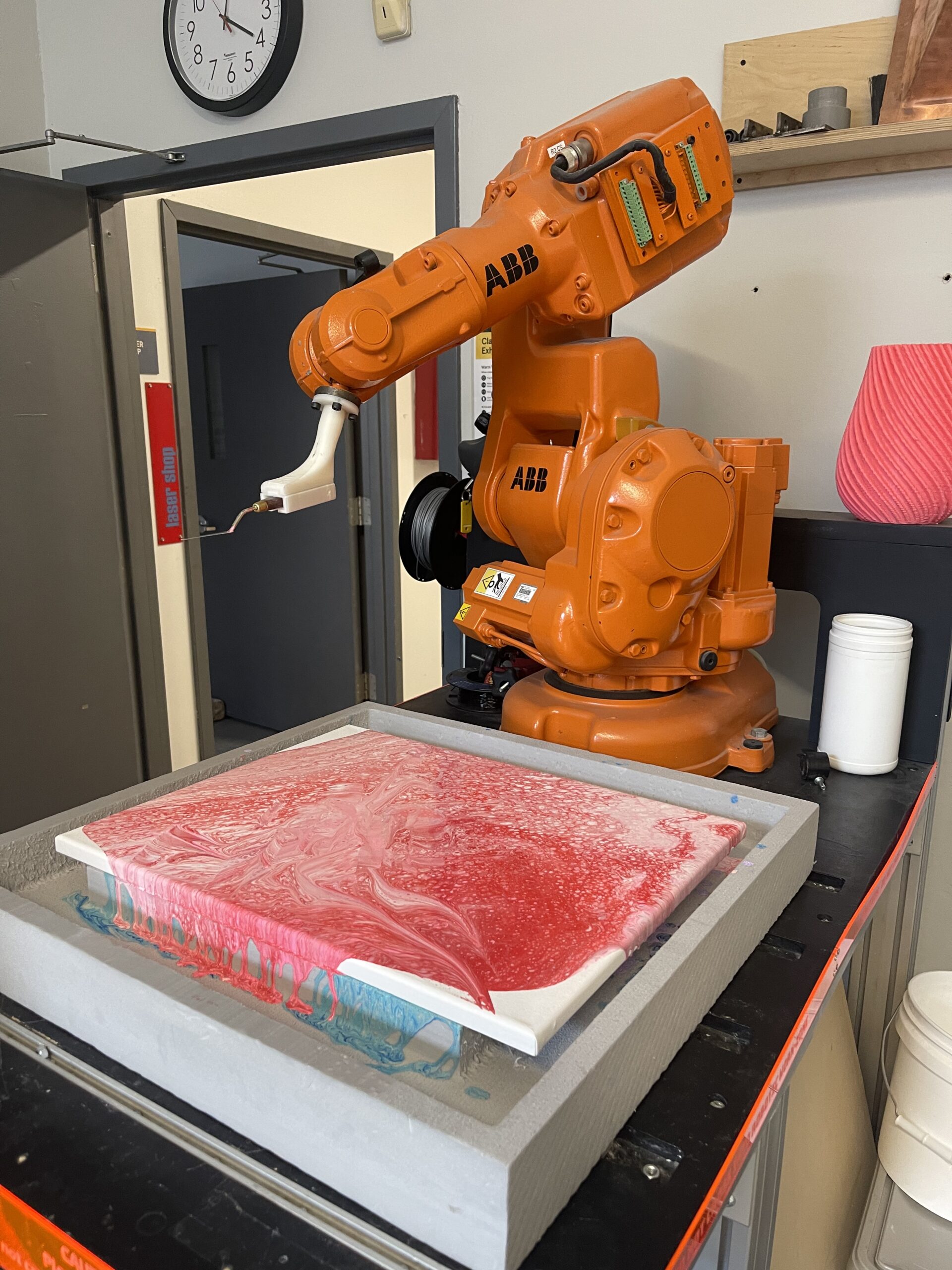

The students sought to limit human bias in the design process by using techniques such as pour-painting, robotics, and artificial intelligence programs.

“The project deviates from a traditional design in that it explores a collaboration between the designer, the material, and the machine,” said Coersmeier. “The Seoul Biennale was a wonderful opportunity to explore this in the context of a large ecological project that could affect the future of urban development.”

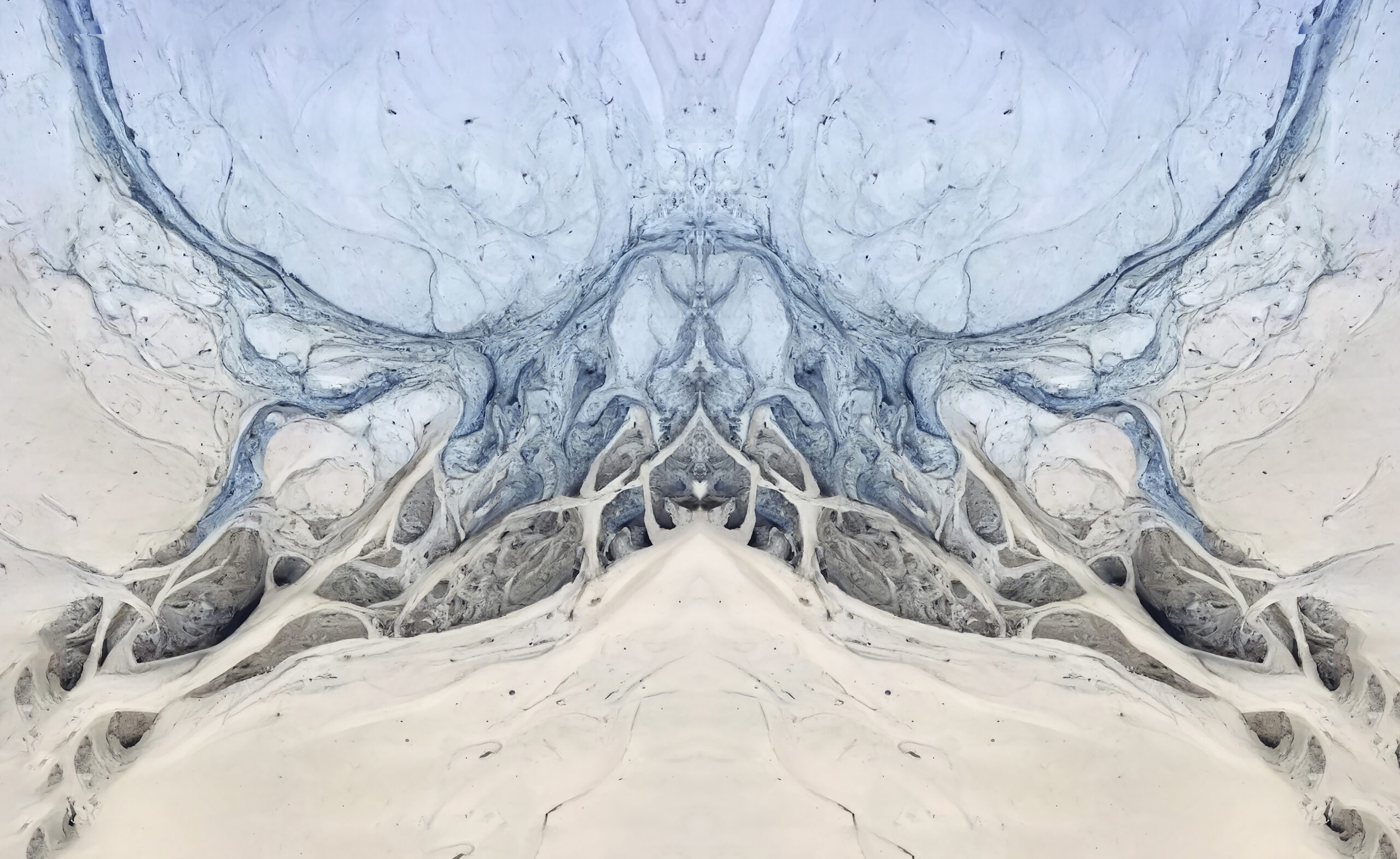

With the recent Seoul trip at the front of their minds, the students marked up canvases with the river’s topographical features. They then mixed paints in cups and placed them face down on the canvasses. When lifted, the paint spread evenly across the surfaces and repellant agents traced the inscribed site information. In the PI-Fab facilities, students equipped the robotic 3-D printing arm with a painter’s knife and gave the machine general instructions for moving across the canvas. Both exercises created what, to an outsider, look like gorgeous abstract images, full of surprising expanses, curves, and intricacies.

The teams then synthesized these images, along with scenes of the Han River and granular site information, with generative programs like MidJourney, Dall-E, Runway, and Stable Diffusion. By controlling the data sets, they were able to elicit outputs that could inform future design decisions.

“It started with the base set of images and then, almost like a recipe, we added different images to the programs,” said Ekam Singh. “If we added image A and B and that’s how we got C, what would happen if we added C and A back together? We laid all of these images out in a complex matrix, arranging them based on the kind of painting, surface, and other factors.”

In this way, the digital programs became like collaborators in the design process. The students split into pairs to handle discrete aspects of the bridge design, from housing components to community spaces, and eventually developed an overall proposal for the Biennale.

Coersmeier has been teaching versions of “Painterly Urbanism” for years and believes that it can help make the built environment more equitable and sustainable for both humans and wildlife. Introducing artificial intelligence into the process adds more potential for creative surprises, insights, and opportunities.

“The city is a complex phenomenon and perhaps a living entity itself and there’s depth and nuance in thinking about the city that conventional approaches don’t always capture,” he said. “I am very aware of the anxieties that are connected to AI, but my position is that we have to train our students to understand this new era because they are the ones who are going to determine where the development of AI is going.”

AI tends to be shorthand for a range of clustered and rapidly evolving technologies: neural networks, machine learning, image generation, chatbots, robotics, and more. Singh credits the Biennale project with clarifying the role of AI in the fields of design and architecture and giving him a sense of how he can harness it in his career.

“All of the decisions are still being made by designers and architects,” Singh said. “So it’s like having this new tool that can process information at a much faster pace. It’s almost like this hybrid holobiont thing, where the man, the machine, and the software are coming together.”