Fourth-year undergraduate architecture students recently envisioned “Green New Worlds” in which environmental policies and solutions would together promote a more just society. The spring 2020 “Rendering the Just Transition” studio was led by Jason Lee, associate chairperson of undergraduate architecture, and Meredith TenHoor, professor of architecture. It centered on how students could use techniques of architectural drawings, renderings, and diagrams to envision a future in which climate-crisis-causing carbon emissions have been drastically reduced.

Emely Balaguera, “A Rehabilitation for Rikers Island”

Fourth-year undergraduate architecture students recently envisioned “Green New Worlds” in which environmental policies and solutions would together promote a more just society. The spring 2020 “Rendering the Just Transition” studio was led by Jason Lee, associate chairperson of undergraduate architecture, and Meredith TenHoor, professor of architecture. It centered on how students could use techniques of architectural drawings, renderings, and diagrams to envision a future in which climate-crisis-causing carbon emissions have been drastically reduced.

“Our goals were to use the representational capacities of architects—part of our students’ disciplinary training—as a way to help visualize policy proposals, to make them more real and into something people could see and debate,” TenHoor said. “But this required a lot of programmatic innovation on the students’ part. They had to learn what others proposed and try to imagine how it would work in a world they wanted to build and represent, often in a specific town or place.”

The students drew on research and policies proposed by frontline communities, or those that are most vulnerable to climate change, and from legislation such as the Green New Deal, which aligns reductions in carbon emissions with job growth and racial and economic equality. Students familiarized themselves with definitions of a “just transition” from organizations like the Climate Justice Alliance and proposals from grassroots organizations so that they could understand local and frontline experiences of the climate crisis. The students were invited to take a utopian approach, imagining a present or future without any barriers of legislation or funding, as they wrote their own policies for a “Green New World” and created projects responding to these ideas.

The student work, which was recently featured in the Architectural League of New York’s publication Urban Omnibus, ranged from healthcare and transportation to decarceration and textile industry reform, all exploring what the role of an architect can be in tackling these issues. Their projects investigated both technical and practical solutions for decarbonization.

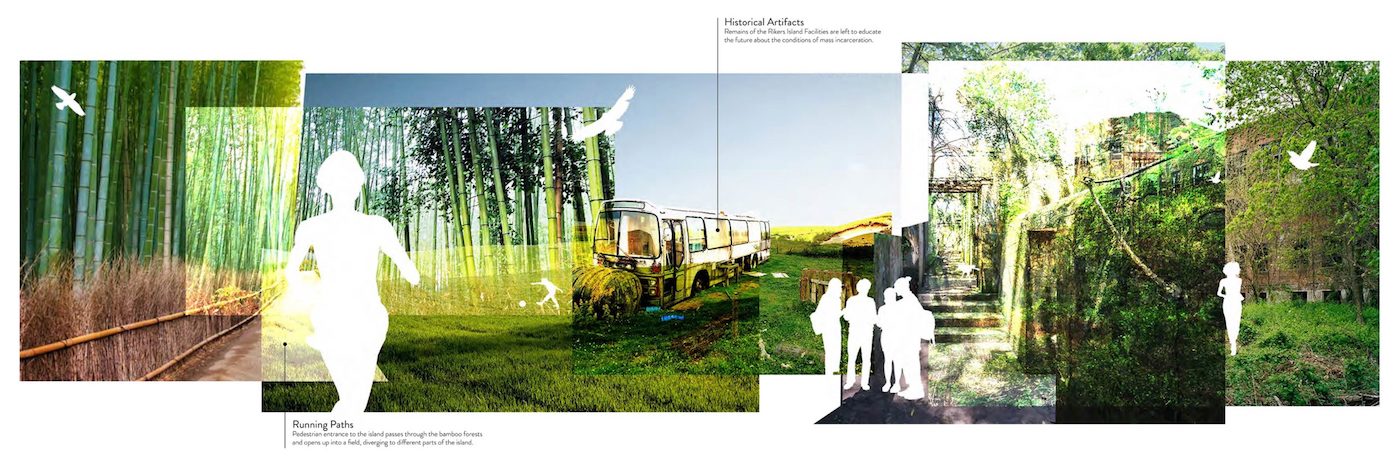

Emely Balaguera, “A Rehabilitation for Rikers Island”

With the planned closure of the Rikers Island jail complex on the horizon, Emely Balaguera imagined a new municipal agency—the New York City Department of Public Assets—which would lead a just transition for the site and empower people working at the intersections of social and environmental justice. The project envisions a new life for the island that engages with the history of the site and its role in mass incarceration, with renewable energy resources, a Museum of Restorative Justice, and recreational amenities like walking trails all constructed amidst cultivated forests and wetlands. Working along similar lines, Kylan Connolly sketched a vision for how reducing prison populations could benefit rural towns around the Great Lakes, as jobs and buildings that are part of the prison industry would be replaced by new job opportunities and local amenities.

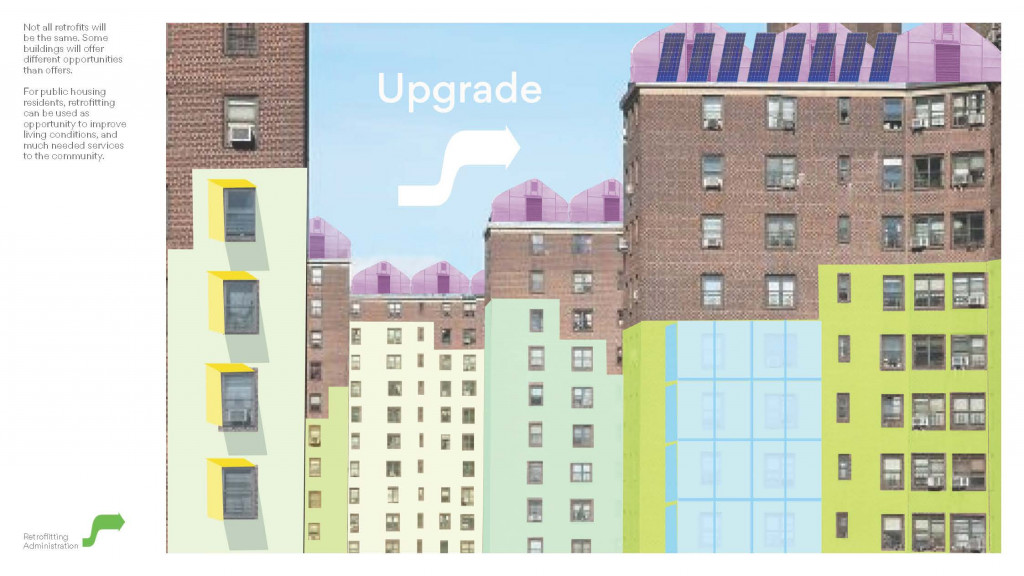

Cal McAuliffe, “Retrofitting Administration”

Cal McAuliffe imagined a new federal agency—the Retrofitting Administration—which would lead the mass retrofitting of buildings in the United States to reduce their carbon emissions, echoing the work of the New Deal-era Rural Electrification Administration that spearheaded electricity access across rural America through co-ops set up in the 1930s. Like that federal initiative, the Retrofitting Administration would create jobs at the same time it added solar shades, panels, and other improvements to enhance the energy efficiency of a range of buildings.

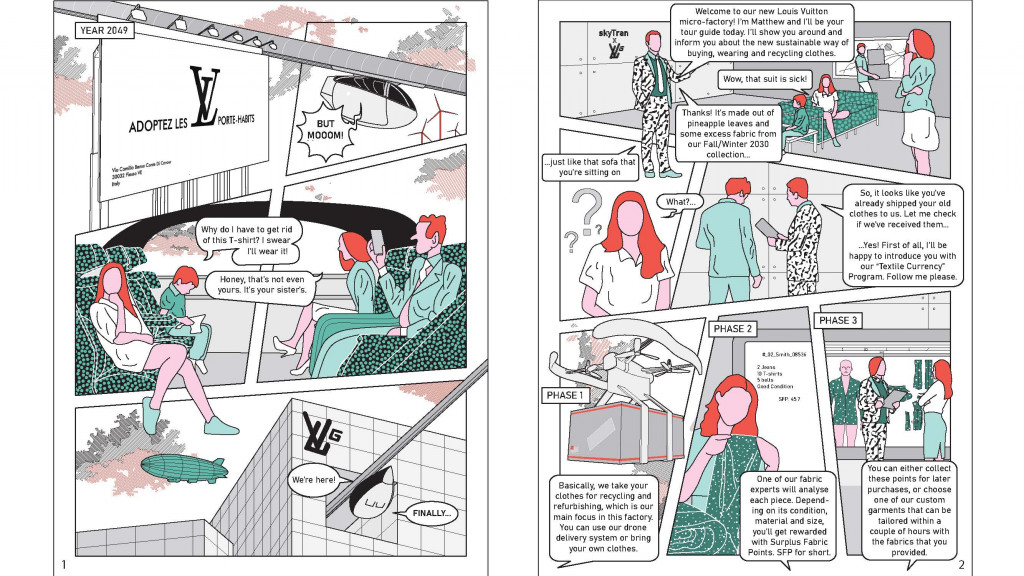

Talya Polat, “A Just Textile Transition”

In “A Just Textile Transition,” Talya Polat created a comic book-style presentation for an imagined bill that would cause a major shift in the textile industry, from its current polluting practices that contribute significantly to carbon emissions and ocean microplastics to a more sustainable system. Micro-factories, with smaller footprints and shorter distances to their consumers, would be able to connect locally with communities and encourage a circular economy, so used clothes could be recycled and refurbished rather than sent to the landfill.

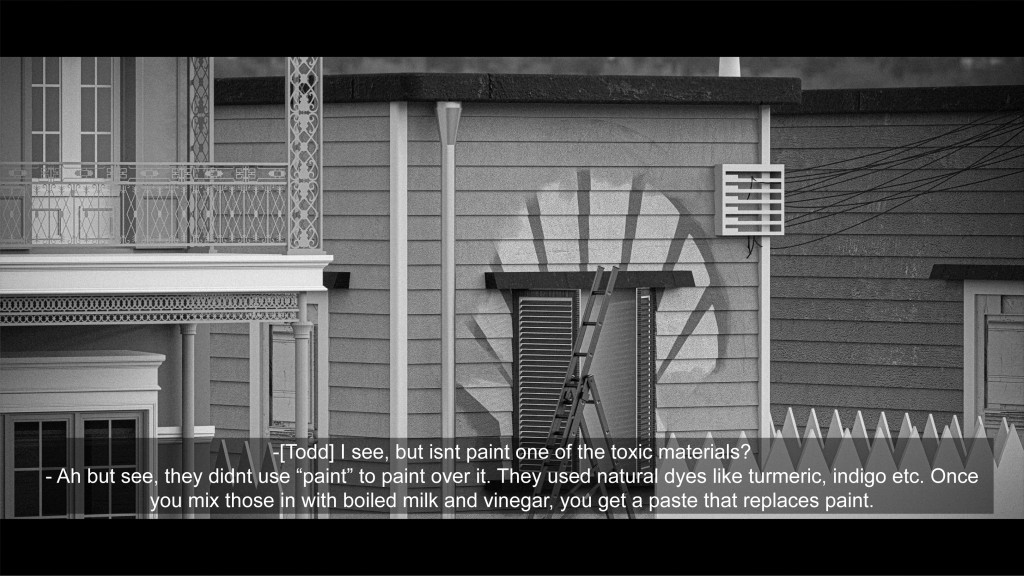

Abhishek Thakkar, “Creole Futurism”

Abhishek Thakkar’s “Creole Futurism” project examined “Cancer Alley,” an area between Baton Rouge and New Orleans where the health of residents is severely impacted by numerous nearby factories. Structured as a series of cinematic stills from a documentary on a fictional class action lawsuit, the project offers a narrative on how residents could push back against petrochemical corporations’ half-hearted attempts to facilitate social and environmental rehabilitation. In this speculative future, Thakkar considered the benefits as well as the shortfalls of corporate-led models for addressing environmental injustice.

Cory Breegle, “Bed-Stuy Pocket Community”

Other students likewise recognized the challenges of equity in potential environmental legislation, such as Cory Breegle who created the “Bed-Stuy Pocket Community.” The project is set in a future where, after the passage of the Green New Deal, residents in Bed-Stuy are battling gentrification by reclaiming land from developers. With a land trust and other initiatives including the creation of structures for urban farming and a micro-power grid, the Pocket Community could provide both environmental amenities and claim agency over the development of the neighborhood.

“Our current system—what people call ‘the market’—is entirely invented, and there is no reason why we can’t invent another system that serves our planet and its people better,” TenHoor said. “This work is part of what I hoped our students would connect to and advance.”

All of the student projects are available to view online. As they were in their fourth year as undergraduates in the School of Architecture, it was the first opportunity they had in a studio to design their own programs, laying the groundwork for their fifth-year degree projects. Lee and TenHoor plan to offer a version of the class again in spring 2021, continuing to encourage their students to look ahead not only to ecological and equity needs in their field but how they can work in partnership with and in support of communities advocating for change.