This year marks 75 years since World War II’s end in 1945. As the world commemorates VE (Victory in Europe) Day on Friday, May 8, here is a look back at how members of Pratt Institute’s community stepped up to creatively rethink the art of deception.

In September 1940, James C. Boudreau, then dean of Pratt’s School of Art, set up a laboratory on campus to research and develop camouflage techniques. Called the Industrial Camouflage Program, it included a course on camouflage, research projects, and field experiments. Boudreau invited Konrad F. Wittmann, an architect with experience in industrial camouflage, and Peter Rodyenko, an Army captain with camouflage expertise, to its faculty. Alexander J. Kostellow, a professor of industrial design, was also heavily involved in the Institute’s camouflage curriculum. The program, with its focus on cutting-edge design and the opportunity it represented to participate in critical defense, was instantly popular and hundreds of art and architecture students signed up for its first day of classes. (As The Prattler reported on February 19, 1941, Boudreau had to tell the 450 students who expressed interest that only 150 could be accommodated in the class.)

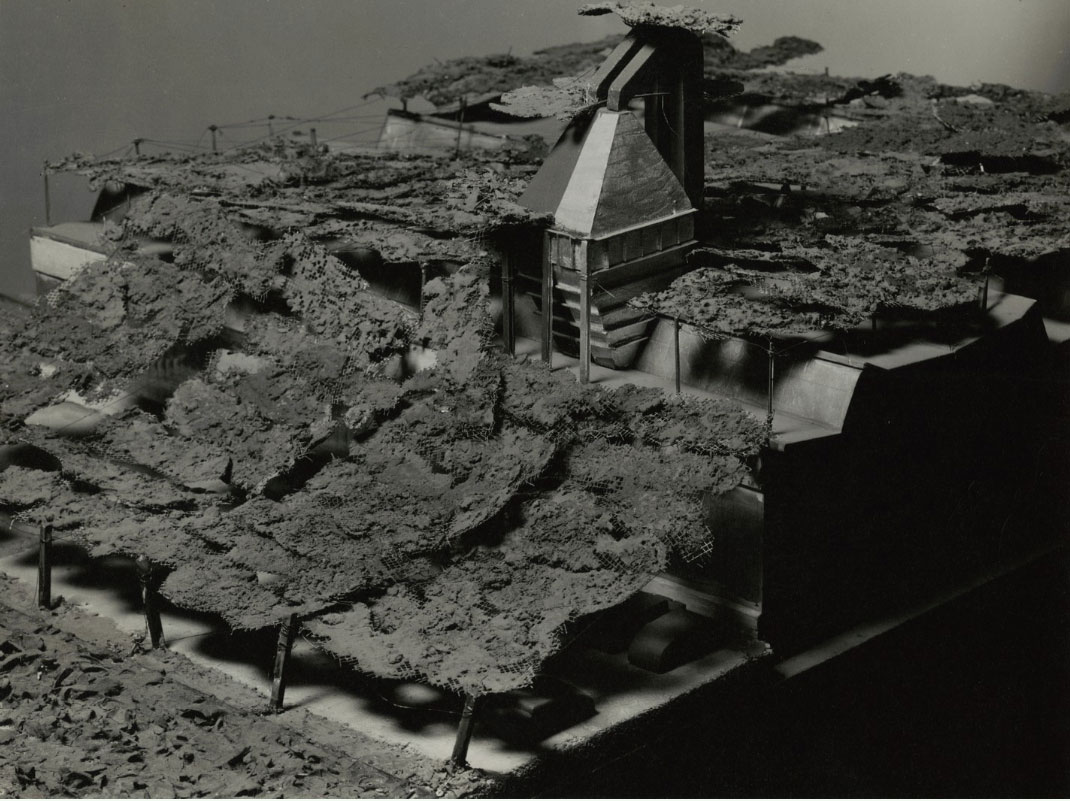

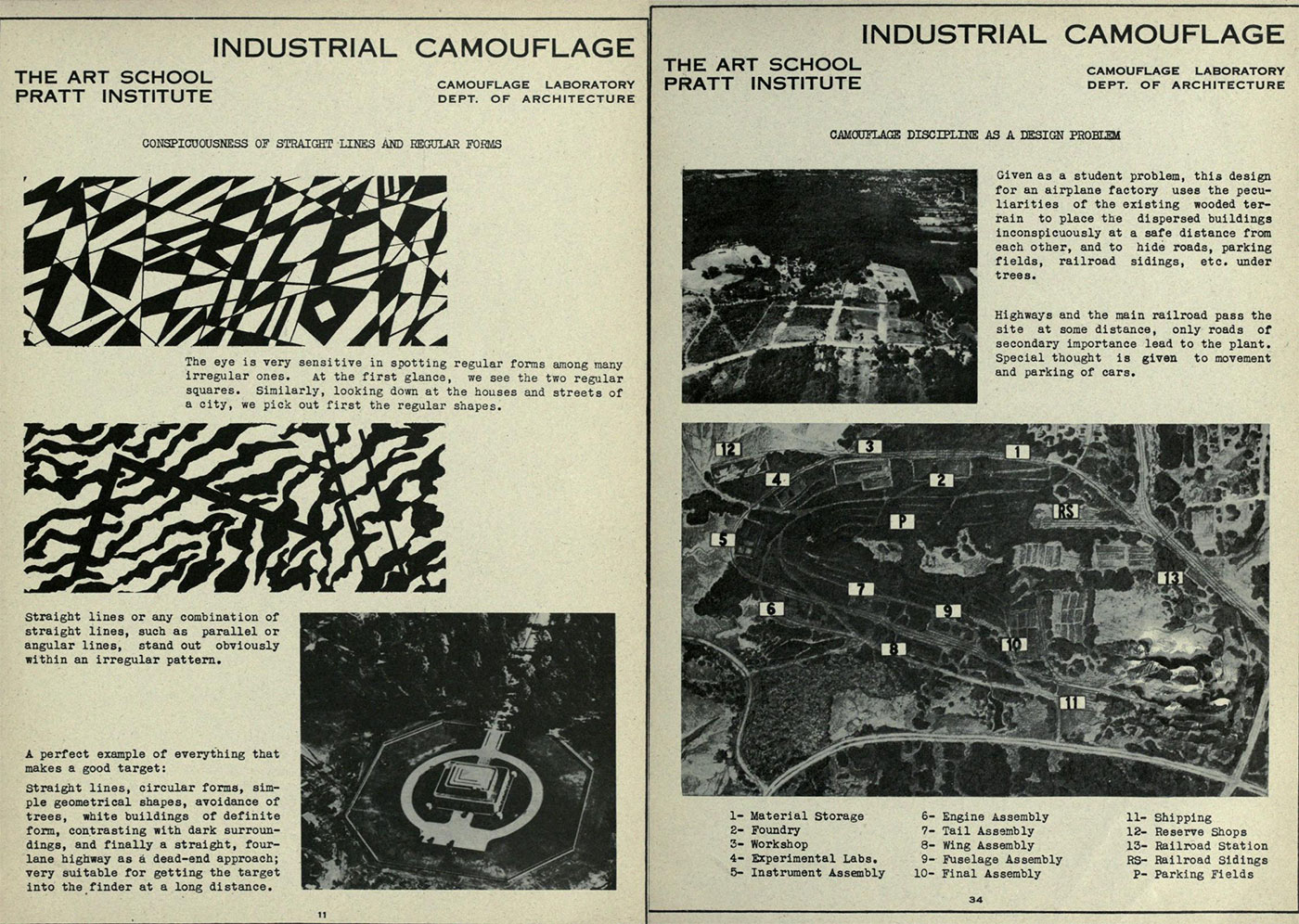

The program had a concentration on how to redesign buildings, military formations, and other essential structures on the ground to better mask them from aerial attacks and surveillance, such industrial plant layouts that could blend into the topography of hills or textured netting that could distort the white reflections of a grain silo. As authors Rick Beyer and Elizabeth Sayles describe in their 2015 book Ghost Army of World War II, the students tested out some of their designs at the Pratt family estate in Glen Cove on Long Island’s North Shore, where “Boudreau, a pilot, would fly overhead and snap photos to show them what their camouflage installations looked like from the air.”

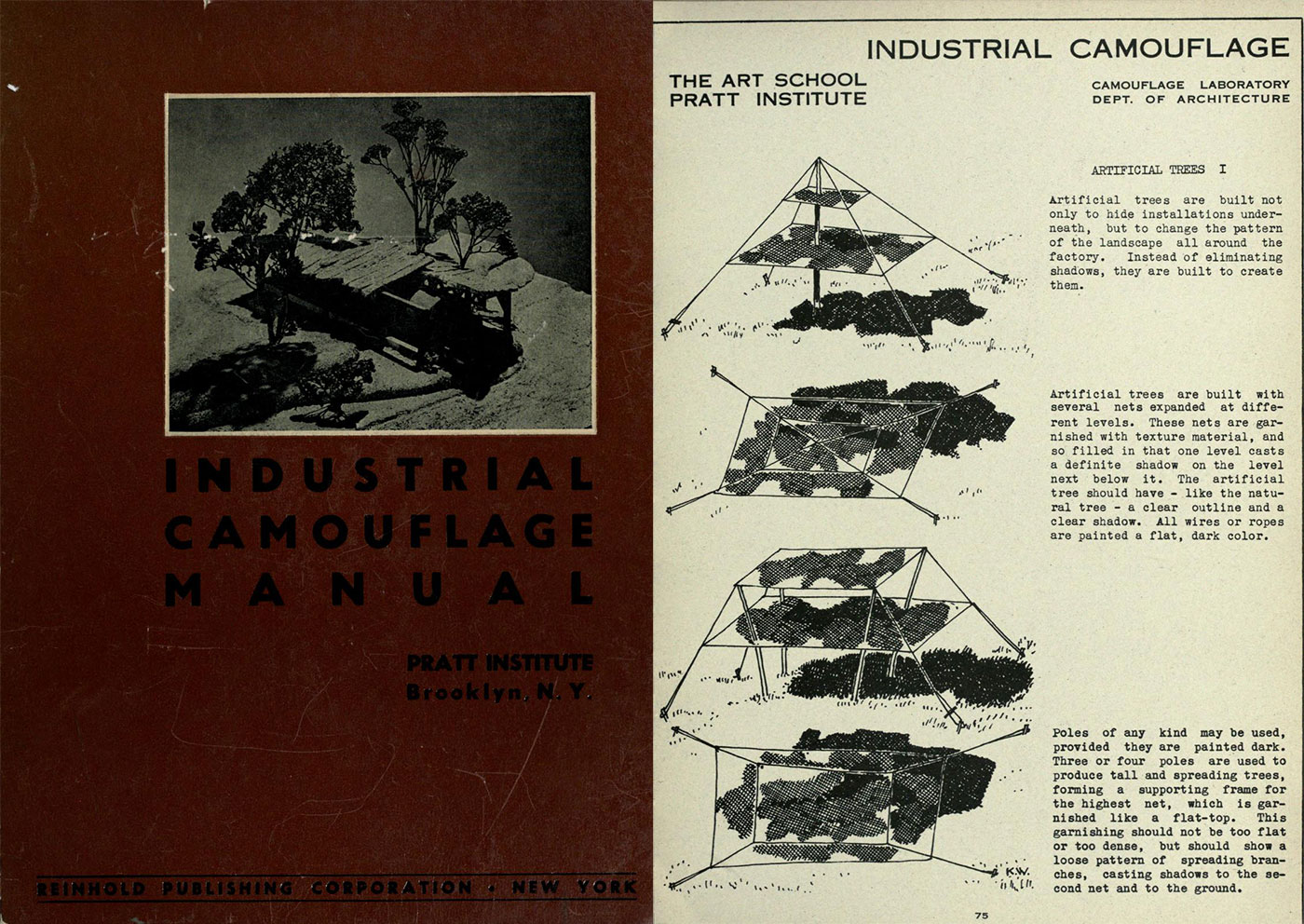

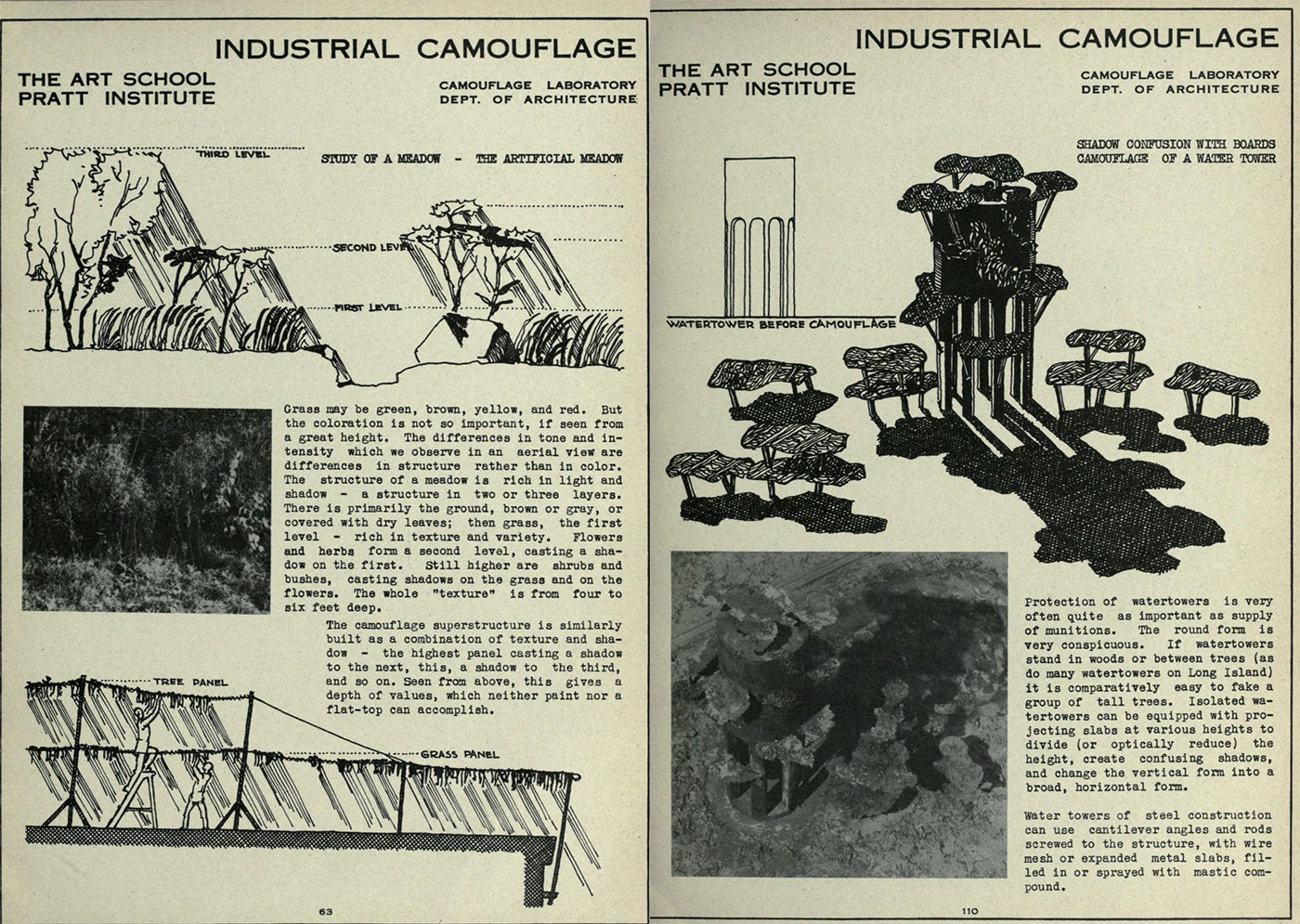

Models from the Pratt program were exhibited in the camouflage section of the 1941 Britain at War at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and in the museum’s 1942 Camouflage for Civilian Defense, A Circulating Exhibition. The results and findings were then published in a 1942 industrial camouflage manual—now digitized on the Internet Archive—in order to “contribute to the all-too-meager study of this fast developing new area of war effort.” The publication included their recommendations on artificial textures to hide people and objects in nature, “shadow confusion” to disguise various types of buildings, and proposals for creating camouflage landscapes with arrangements of natural and fake trees made from nets.

Wittmann explained in the publication that they were especially interested in how 20th-century warfare had influenced thinking around architecture and city planning, as previously “we designed a factory with ground-plan and elevation, but it is no longer unimportant how this looks from the sky.” Buildings and streets with irregular patterns, rather than grids of lines, made for more difficult targets; water towers, like those they employed as examples on Long Island, stood out, yet in a group of tall trees—whether natural or dummies—their collective shadows could conceal the important structure.

The program was just one aspect of Pratt’s support of the defense effort, which escalated after the United States entered the war. As a Pratt catalog in 1943-44 stated, for “the duration of the war, all courses have been re-oriented so that they are thoroughly adjusted to military or civilian war activities.” With Boudreau actively engaged in recruitment to camouflage battalions, several of the students in the Industrial Camouflage Program joined the 603rd Camouflage Engineers, or the “Ghost Army,” part of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops formed in 1944. There they found a way to use their camouflage studies on the battlefields.

The covert unit was focused on visual and aural deception in the European Theater of Operations. Using inflatable tanks, visual illusions, sound effects, and other techniques, their goal was to cause confusion about the location and number of Allied troops, tank formations, and artillery batteries.

Several Pratt alumni served in the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops defense force, including Bernard Bier, Ed Biow, Victor Dowd, Ned Harris, Ellsworth Kelly, George Martin, Irving Mayer, Mickey McKane (Irving Nussbaum), Elmer Mellebrand, Richard Morton, Seymour Nussenbaum, Robert Petrucci, Bill Sayles, Arthur Shilstone, and Bob Tompkins. A number of these veterans shared their stories in a 2008 issue of Prattfolio, recalling their secretive tactics and the challenges of continuing an art practice in war.

“We put butterfly nets and garlands over the real tanks to make them invisible from aerial observation,” Dowd, who died in 2010, described, adding that in the experimental process, and the time he had to draw between maneuvers, it “was a good extension of the Pratt experience.” Shilstone remembered how in “the beginning we did camouflage and disruptive paintings on trucks and buildings,” their campaigns taking them to England, Normandy, northern France, Luxembourg, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany. Like Dowd, he kept sketching, and said that his Foundation year at Pratt prepared him for the unpredictable settings of conflict: “The training made an artist out of me, no doubt about it.” Ned Harris, who died in 2016, had taken night classes at Pratt from the age of 16 to 18 and then worked as a graphic designer. On the European fronts, he picked up a used German hand grenade to hold his art supplies so he could sketch people and places during roadside breaks. “I made the first drawings when I didn’t have to worry about pleasing anyone,” he said.

As much of the valuable work of this “phantom army” was classified until the 1990s, its impact has only recently received historical attention, such as the Ghost Army documentary released in 2013 featuring interviews with Biow, Dowd, and Shilstone. As with the pioneering Industrial Camouflage Program at Pratt, their work used ingenuity and design to reimagine defense, saving lives and ultimately contributing to ending the war.